The events unfolding in Ukraine right now represent a redrawing of the map of Europe largely unprecedented and in a way not seen since the end of the Second World War and certainly not since the fall of the former Soviet republics some three decades ago.

That a major conflict could be underway on the immediate borders of Europe is a cause of concern for the European Union, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) and western allies — forcing an immediate rethink of policies and conventions we had all come to expect in modern times.

Without the context of the fighting now engulfing much of eastern Ukraine, the news that Berlin would be shipping 2,700 Soviet-era “Strela” surface-to-air missiles to the embattled nation would have been disconcerting — nay, alarming — to Germans and Europeans alike, and would have caused deep and irreconcilable divisions within the ruling coalition of Socialists, Greens and Liberals that currently control the Bundestag in Berlin.

Special security operation

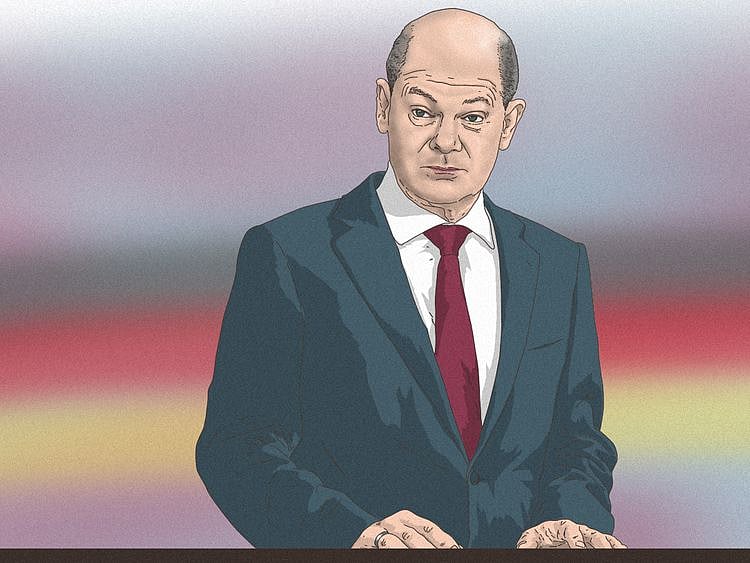

But the Russian attack on Ukraine — the Kremlin refers to it as a “special security operation” — has turned long-held conventions upside-down. In Germany itself, there is broad support for the extensive and expensive measures introduced by Chancellor Olaf Scholz over the past week to support Ukraine.

These 2,700 missiles would come out of the depots once overseen by Soviet-controlled East Germany, which reunited with West Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It is but the latest tranche of support for the government in Kyiv, with Scholz’s government deciding last weekend to supply Ukraine with 500 US-made surface-to-air Stinger missiles and 1,000 anti-tank weapons.

According to reports from Reuters, the missiles are ready to be transported but await final approval by Germany’s Federal Security Council.

For decades, Berlin has not been inclined to provide direct military support to any side in any conflict — a position that reflects the nation’s long and difficult history leading up to the seismic events of the Second World War. Since then, Germany, either in the Cold War entity governed from Bonn, or in the united nation recreated by the fall of the Iron Curtain, has been a peacekeeper rather than peacemaker, with careful consideration given to any military mission beyond any versions of its borders.

A historical shift

Now, with Ukraine, there is “a historical shift,” as Scholz himself noted. “In this situation it is our duty to support Ukraine’s defence against the invading army of Vladimir Putin to the best of our ability,” he said after hostilities began.

The 63-year-old Chancellor has been involved in German politics for decades and fully understands now the implications of the decision he and his government have taken. His Socialist Party has been around since the formation of modern Germany and the chancellorship of Otto von Bismarck, a party that opposed and suffered during the Hitler years.

In part, his election victory last September stemmed from his hand on Germany’s finances at a time the largest economy in Europe — like those everywhere else too — stalled and entered economic hibernation as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

He convinced Germans, notoriously tight when it comes to providing direct federal assistance to the economy, that the nation was strong enough to cope. By 2022, Germany will have taken on €400 billion in new debt — and he campaigned on a promise that it would be able to grow out of the new debt levels.

He campaigned on being a continuation to the safe hand on the tiller proved by almost two decades of Merkel rule, promising continuity and providing strong leadership for the rest of Europe that will speak with one unified voice built from a position of pragmatism and compromise — until last week.

Days before, he had visited the Kremlin and met President Vladimir Putin in an attempt to avert any hostility. That, and all other diplomatic entreaties clearly failed.

Reversal of policy

Last Saturday, his government announced a decision to provide 1,000 anti-tank weapons and 500 surface-to-air missiles from German military stocks to Ukraine as soon as possible. At the same time, Estonia and the Netherlands received permission from Berlin to transfer the German-made weapons to Ukraine, whereas previously such permission had been denied.

The move reverses Germany’s long-standing principle of not sending or selling weapons to conflict areas. The irony is that despite the policy, Germany is ranked fourth globally in arms exports in the world after the United States, Russia and France.

Poll after poll over the past decade show that a majority of Germans were opposed to every foreign deployment of the Bundeswehr in conflict zones from Afghanistan to Mali.

Berlin is happy to sell weapons, but it also maintained a pacifist stance. Until now.

Explaining the seismic shift in Germany’s policy, Scholz added, “We are not alone in defending peace”.

“We will never resign ourselves to violence as a means of politics,” he tweeted. “We will not rest until peace is secured in Europe.”

And the former finance minister is putting German’s money where his mouth is, announcing that the government would allocate €100 billion extra for the Bundeswehr — armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany and their civil administration and procurement authorities.

Berlin has also cancelled the Nordstrom 2 pipeline, risking far higher energy prices for his nation largely dependent on Russia for its gas. Scholz also gave his backing to isolate Russia from the international financial payments system Swift.

The supply of weapons, military funding and touch action on economic sanctions all show there truly is a new leader in Berlin. The measures have distinctly set him apart from Merkel. From now on, he is indeed his own man.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.