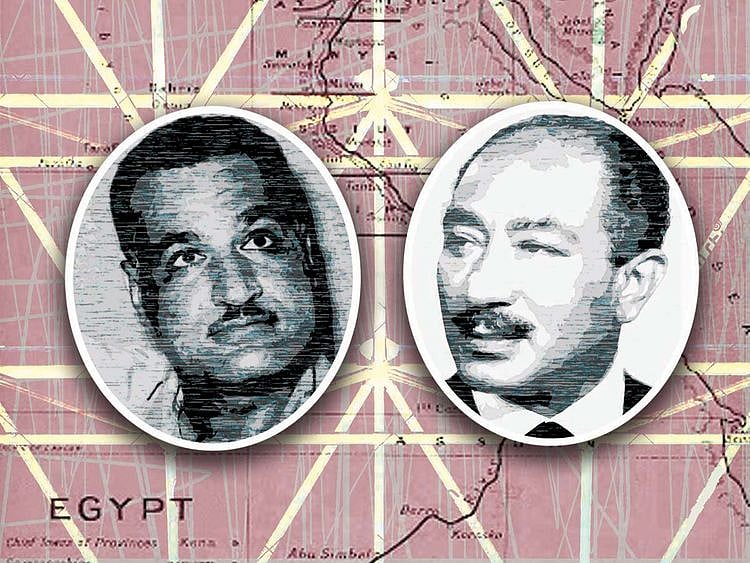

Less than four years after the death of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, his successor, President Anwar Sadat decided that the best solution to Egypt’s economic problems was to abolish the Socialist system his predecessor, Nasser, believed in and was loyal to until his death on September 28, 1970.

Sadat’s meetings with representatives of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), meant to secure loans to help revive the economy, ultimately led to major changes in Egypt’s economic regime - abandoning the socialist system and embracing a free-market capitalist system.

In those meetings following the October 1973 war that led to near bankruptcy in the Egyptian treasury, Sadat had to choose between moving forward with the socialist approach that began with the July 1952 revolution or going along with the two international institutions’ terms to secure those loans and he chose the latter, thereby abolishing of the government’s subsidies and floating the prices of many essential products such as bread and fuel, practically ending the era of the revolution. (The 69th anniversary was marked at the weekend)

Sadat was planning to go in that direction anyway, probably the day he took over. Before his meetings with the World Bank and the IMF, with American blessings, he had cancelled free trade agreements with the Eastern European Socialist Block and severed military ties with the Soviet Union that were established during Nasser’s days.

22 years after the 23 July Revolution

So, just 22 years after the 23 July Revolution, which changed Egypt’s modern history, Egypt abandoned the entire revolutionary doctrine. The revolution became part of the national nostalgia, to be celebrated every year. The republic that was born after the mid-1970s has nothing to do with the revolutionary republic that ended the Monarchy in 1952.

The reasons for that revolution and the justification to end it less than two decades remain an important part of the political discourse in Egypt and the Arab world until today.

The 1948 Palestine War was a turning point in Egypt’s modern history. The defeat in that war, which led to the establishment of Israel, was probably the last nail in the coffin of a feeble monarchical system. The ills of that system were visible to all. But following the humiliating defeat in Palestine, the army decide it was time to move.

A group of ‘Free Officers’ led by the charismatic Nasser took over major ministries on the night of July 23 and declared through the radio that the King, Farouq, was stepping down. After a transitional 8-month period, the republic was declared in 1953.

The war in Palestine may have been the spark of the revolution, but there were several compelling reasons that led to the overthrowing of the 150-year-old rule of the Mohammed Ali dynasty- the prevailing social injustice, British rule and the inability of the main political parties to reform the system.

Those problems, Nasser wrote in his book, Philosophy of the Revolution, were hindering Egypt from taking its “proper role on the world map.” The great nation of Egypt, one of the cradles of human civilisation, deserved a better government, Nasser added.

Economic and social reforms

Therefore, the revolution focused in its earlier years on economic and social reforms. King Farouq’s rule disregarded the majority. It was basically a feudal system, where the King, his family and those close to him owned most of the land in which the majority of Egyptians worked in as hired hands- it was quasi slavery. The peasants had no rights and no means either to support their family nor had any access to education and health services. There was no real middle class.

There were only the very rich and the very poor. The British rule which began in 1882 made things worse. Their heavy-handed control of Egypt’s foreign and defence policies humiliated the proud Egyptians. The King was widely seen as a mere puppet who encouraged corruption among his inner circle to ensure loyalty.

The 23 July revolution was based on six basic principles as announced later by Nasser: “eliminating feudalism, ending British colonialism, ending the capitalist system, social justice and the building of a healthy democratic life, and building a national army.” It was supported by millions of peasants, workers who lived under the poverty line.

The new system succeeded in officially eliminating feudalism by restricting the amount of land one can own, giving the rest of the land to the peasants who worked on those lands. It nationalised trade and industry, which were controlled mostly by foreigners.

It introduced free education which led to the establishment of a new class in Egypt, an educated affluent middle class- the poor became university professors, judges, ambassadors and ministers- jobs that were restricted to the higher classes during the monarchy.

In its second and third circles, as Nasser wrote in his manifesto, the new republic embraced the idea of Arab nationalism, supported the then occupied Arab states to get independence, supported the African fight against colonialism and played a leading role in the creation of the Non-Aligned Group.

Nasser’s accomplishment continued as he nationalised the Suez Canal and built the Aswan High Dam with the help of the Soviet Union. The dam could very well be Egypt’s most important project in modern history, according to most Egyptian historians. As it began operating in 1968, electricity was introduced to thousands of villages and industrialisation was accelerated by providing uninterrupted and cheap power.

On the other side, Nasser’s critics argue, the revolution turned Egypt into a police state. The Mukhabarat (the intelligence service) was in control of every aspect of life. Political democracy was non-existent. Only one party was allowed to run for office- the ruling Arab Socialist Union, which was abolished later by Sadat.

Today’s Egypt is a multi-party system with relatively freer media. Many would like us to believe thus that it has nothing in common with Nasser’s Egypt. And that the republic was changed forever by Sadat, when he decided to join the free market world with his Economic Open-Door Policy. But looking intently at today’s Egypt only underscores the fact that all these achievements would not have been possible without the 23 July revolution.

Egyptians may pay symbolic homage to revolution every year. But they know very well that those bold initiatives taken by Nasser, such as the land reforms, education reforms, nationalisation of the Suez Canal, building the Aswan dam and the establishment of an industrial sector, are the real engines that keep today’s Egypt running.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.