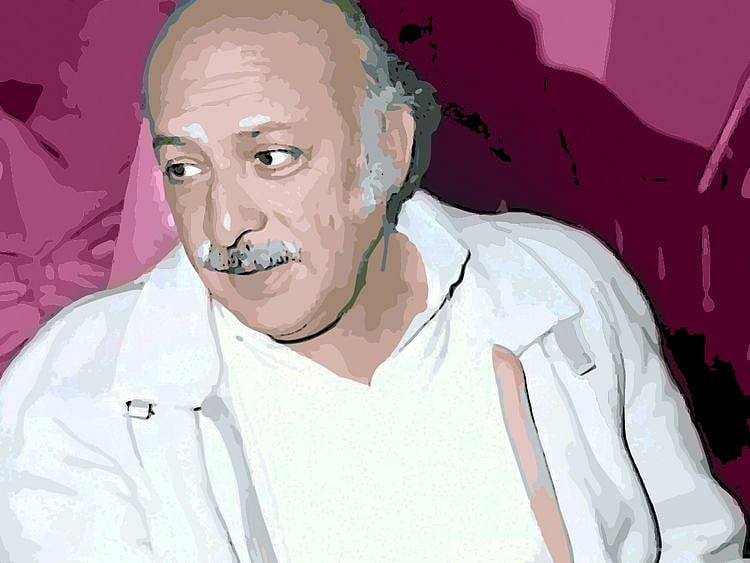

Defying the odds, Mudaffar Al Nuwab was not just a poet

His work remains alive as one of the most inspiring Arabic literature in past 60 years

One winter day in 1956, on board a train travelling from Baghdad to Basra, in Iraq, a woman, in her 40s with a subtle vestige of a past beauty, seemed a little agitated as the train slowed down nearing the small village of Om Shamat. Her silent tears didn’t escape the man sitting at the opposite seat. The curious man had to ask. As if she was waiting for someone to ask, she told her sad story.

The woman was from that small village. Years ago, she fell in love with her cousin but her family, in line with the prevailing customs those days which considered love a disgrace to their honour, refused to allow the marriage. Fearing for her life, she ran away to Baghdad, where she could hide away in the big city. The painful memories came back to her as the train pulled into Om Shamat.

Her story certainly was not unique. It was just like thousands of similar stories of lost love and cruel social customs in this part of the world. But we would not have heard of this specific story, or the village of Om Shamat had it not been for that man, a teacher from Baghdad, who went on to tell her story in what has become one of the most iconic poems in Arab history.

‘The Rail and Hamad’, written in colloquial Arabic, was legendary poet Mudaffar Al Nuwab’s first serious work. It became a turning point in Iraqi literature, especially after it was sung by a popular Iraqi singer few years later. Al Nuwab died last week in Sharjah following a long battle with illness. He was 88.

Poetry as historical log

It is said that poetry is the record of the Arabs, a historical log where the most important events in their thousands of years history are noted; sometimes celebrated and often disparaged. Pre-Islam battles, recent years conflicts, and prominent people’s births or deaths have all been recorded by Arab poets.

Poets sometimes just describe the event, but many of them took to poetry to offer commentary and criticism. Following the June 1967 war, in which the Arabs suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the smaller and less equipped Israeli army, Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani declared, in one of his most famous poems, ‘The death of the Arabs’.

Despite his Nasserite tendencies, his now iconic poem was full of criticism of the pan-nationalist leader, Egyptian president at the time Jamal Abdul Nasser. The poem was understandably banned in Egypt and Qabbani himself was deemed a persona non grata in the country.

In a later interview, Qabbani said he had to write to Abdul Nasser who seemingly was not aware of the decision and ordered that the poem be published in Egyptian newspapers and that the poet is welcome in Egypt anytime.

Immortal work

Mudaffar Al Nuwab was one of the great poets who recorded important events in his immortal work. And because of his words, those events tend to remain alive in our memory. Moreover, his poems that dealt with such monumental happenings, especially in relation to Palestine, have had rare impact on the Arab public opinion.

In those days, where the media and communication were not as instant as today, we even might have never learnt of or fathomed the whole scope of many tragic events. The credit goes to Al Nuwab, the forever Arab nationalist, and the great intellectuals like him who endured the pain and often the wrath of authorities just to put the word out.

One of those events, and one that historians argue was the actual start of Lebanon’s slide into the civil war, is the massacre of Tel Al Zaatar in 1976.

Tel Al Zaatar was a Palestinian refugee camp in the eastern part of Beirut. A one square kilometre shanty neighbourhood with a population of more than 30,000. In the height of the conflict between Palestinians and Lebanese Christian armed militias, heavily armed groups surrounded the camp with the aim of uprooting it from the mostly-Christian area.

The camp was besieged for 52 days beginning in June 1976. The camp was left alone defending itself against the better armed militias (Pierre Gemayel’s Falange Party, the Free Patriotic Party’s Tiger Militia led by Camille Chamoun, Tony Frangieh’s Zgharta Liberation Army militia) who were also supported, historians say, by both the Syrian army and Israel.

The militias cut the power and water supplies and banned all food and medicine shipment to the camp. Survivors of the massacre later said that the camp residents were forced to eat dogs, cats, and tree leaves to survive. For 52 days, the helpless residents were left to their fate enduring hunger, disease and ongoing shelling.

Infamous massacre

Finally, in August and as the defence of the camp finally collapsed as they ran out of food, water and arms, the militias stormed the camp and the genocide began. The armed thugs of the militias massacred more than 3,500 men, women, and children.

The massacre is considered the worst atrocity in the Arab world’s modern history. It was the start of the eradication of the Palestinian presence in Lebanon which was sealed when Israel invaded Beirut six years later.

Lamenting the ‘fall of the capital of the poor’, Al Nuwab’s poem, ‘Tel Al Zaatar’, one of his longest works, told the whole story and rallied the Arab public opinion to stop probable subsequent atrocities against possible massacres against the Palestinians and forced the Arab governments to send an Arab force to separate the warring parties in Lebanon.

The Iraqi-born Mudaffar Al Nuwab didn’t write anything after 2005 when he began his long battle with illness. That year, his mother, said to be his greatest influence, died in Iraq. He hadn’t been able to see her for decades as he escaped Iraq in the late 1960s after years of prison, torture, and persecution by the subsequent Baath regimes because of his scathing criticism and communist affiliation.

His long journey of exile, in several Arab and Eastern European countries, ended last week. We lost a great poet, but his work remains alive as one of the most inspiring Arabic literature in the past 60 years.

Critics say he was the conscience of the simple Arab. Some say he was our Don Quixote. But his importance transcends that, he was more than a great poet who recorded history in his work. In his unique way, he defied all the odds to provide context to that history. And succeeded.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.