Also In This Package

Vladimir Putin is making final preparations to try to win next Wednesday’s referendum and extend his term in the Kremlin. While the ballot is primarily being seen through the lens of Russian domestic politics, it could have profound implications for international economics and politics too, especially given his growing closeness to China.

Putin is widely criticised abroad, especially in the West, yet he remains popular in much of Russia. This week’s vote could therefore clear the way for him to stay in power till 2036 — much longer than other major leaders currently on the world stage, with the potential exception of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Xi is becoming Putin’s closest international ally and may remain in power for life after the National People’s Congress removed the two-term limit on his presidency.

For Putin to stay in power potentially into the 2030s too presumes he will win the referendum, remain healthy enough to stay in office into his 80s, and that his popularity endures. That is far from a foregone conclusion, especially if his political luck finally goes south fuelled by potential foreign policy misadventure, or domestic economic travails.

Pre-pandemic, the forthcoming referendum was the centrepiece of Putin’s political calendar this year, but had to be postponed from April as coronavirus cases surged. However, he is now doubling down on Wednesday’s date, and rescheduled a massive Second World War victory anniversary military parade in Red Square, due to be held last month, for last week (June 24) to whip up national pride in the days leading up the ballot.

The constitution currently prohibits any person being elected more than twice consecutively so, as of now, Putin is required to step down from power at the end of his latest term in 2024. Already his period in office has been extraordinary with him serving as prime minister or president since 1999, a longer period at the top than all the Soviet Union’s supreme leaders, except Joseph Stalin.

Putin's grip on power

The fact that Putin could, plausibly, remain in power well into the 2030s, besting even Stalin’s approximately three decades in office, underlines his remarkable grip on power over 20 years after succeeding Boris Yeltsin. In so doing, he has proved skilled in tapping into the post-Cold War national mood by forging a new sense of patriotism fuelled, during much of the period, by a growing economy.

This theme of national unity, and seeking of global respect, is central to Putin’s continued appeal and it is no coincidence that he has engineered the referendum soon after the anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany. Much of his mission since assuming power has been trying to restore Russia’s geopolitical prominence and prestige through gambits like the annexation of Crimea and the Syria intervention.

Yet, while this has — so far — generally played well domestically for him, it has resulted in frostier relations with the West, and a key question remains in coming years how the relationship, specifically with the United States, will fare. Putin and Trump had hoped for a warming in relations. However, events during the first three years of Trump’s presidency diminished, at least for the foreseeable future, the window of opportunity that may have existed for this to happen.

US sanctions sour Russia ties

Here it is not only the fact that the Trump team had been under significant pressure over the congressional and FBI investigations into alleged collusion with Moscow during the 2016 US presidential campaign, but also new US sanctions have made relations trickier. Moreover, there have been significant US-Russia foreign policy tensions, including the Middle East such as the spike in tensions after US missile strikes targeted at Syria in 2017 following an earlier poison gas attack committed by the Damascus regime.

With Moscow’s relationship with the West so chilly, Putin has increasingly asserted Russian power in other areas of the globe from Asia-Pacific to Africa and the Americas. Take the example of the Far East where he has met frequently with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to try to foster joint economic activities in the disputed islands off Japan’s northern-most main island of Hokkaido.

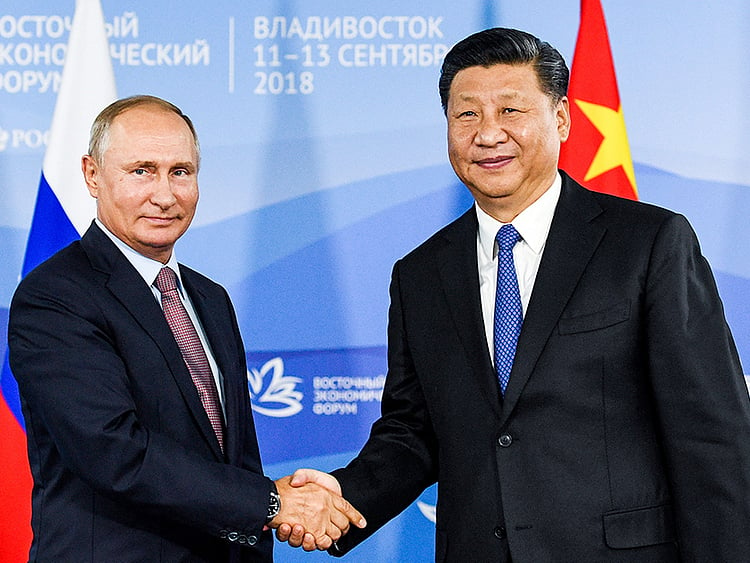

Yet, it is Xi with whom the Russian president has formed his strongest international relationship on both the economic and political fronts. Here, it is not just growing bilateral warmth driving relations, but also the current frigidness of both of their ties with the United States.

In this context both Beijing and Moscow are working more closely together not therefore just to further bilateral interests, but also to hedge against the prospects of a continuing chill in US ties.

This underlines why the implications of the referendum go well beyond the Russian domestic political landscape. With Moscow’s ties with Washington and the wider West so frosty, a Putin presidency that extends well beyond 2024 may well see him opting for an even closer economic and political relationship with Beijing, especially given his rapport with Xi.

— Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.