Uncovering secrets of Al Bastakiya’s windtower houses

Peter Jackson, the co-author of Windtower – the Merchant Houses of Dubai, tells Shilpa Chandran how the book evolved from a short monograph in 1975 to a coffee table book through extensive research, interviews and painstaking documentation

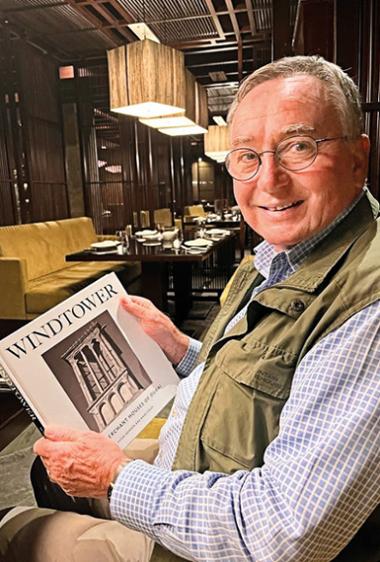

Anyone familiar with this region will be cognisant of its intriguing, yet curiously attractive traditional windtowers. Bringing their prominence to the forefront through decades of research is Peter Jackson, Architect Advisor in the Ruler’s Office in Sharjah, and co-author of Windtower – the Merchant Houses of Dubai.

The book, researched and written with social geographer Anne Coles, launched its 2021 edition that was showcased at the Emirates Literature Festival earlier this year.

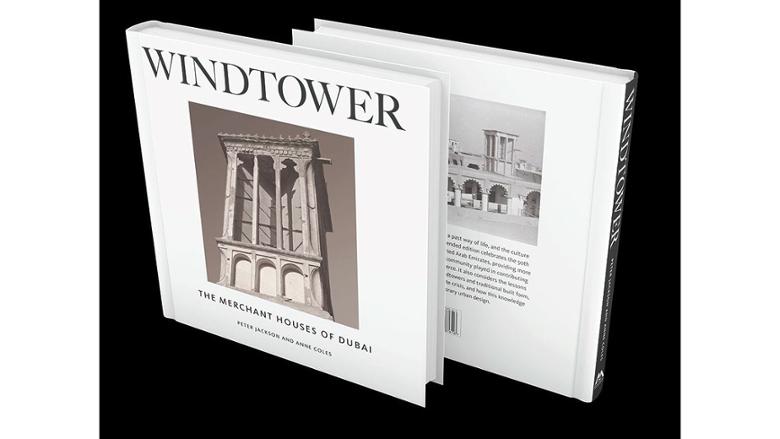

First published as a short monograph in 1975, and then as a book in 2007, it evolved through extensive research and interviews, resulting in a unique record and documentation of the once-thriving Bastaki community in the old Al Fahidi district of Bur Dubai.

Peter came to Dubai as a young student during his practical year-out in January 1972, when he found a job assisting the British architectural firm, John R Harris Architects. Forever passionate about history, the exotic and oriental landscapes of Dubai immediately fascinated him.

“I came to the UAE as an architectural student exactly 50 years ago,” he says, in an exclusive interview with Friday. “Dubai was tiny then, with just around 75,000 people. The airport was brand new. It was very exciting, and there was a real buzz to the place. Oil had been found, though not in large quantities. New roads had already been built dividing the flat sabqa desert into future city blocks, complete with street lights, but nothing in between.

“I was fascinated especially by the Creek, and then Friday trips up to Ras Al Khaimah for fish and chips lunch at the hotel there, exploring on the way all the small towns and villages along the coast. They were really interesting times and I just wanted to learn more about the country and its architecture – there was so much to learn.”

In 1973, Peter met Dr Anne Coles who in the late 1960s had been working with the women of Al Bastikiya, through a newly established local Women’s Society. She had come to learn much about the nature of these homes and the important part they played in ameliorating the region’s harsh summer climate, architecturally, but also through summer migration, both to the mountains, and vertically within the home, up to summer accommodation on the first floor or on the roof.

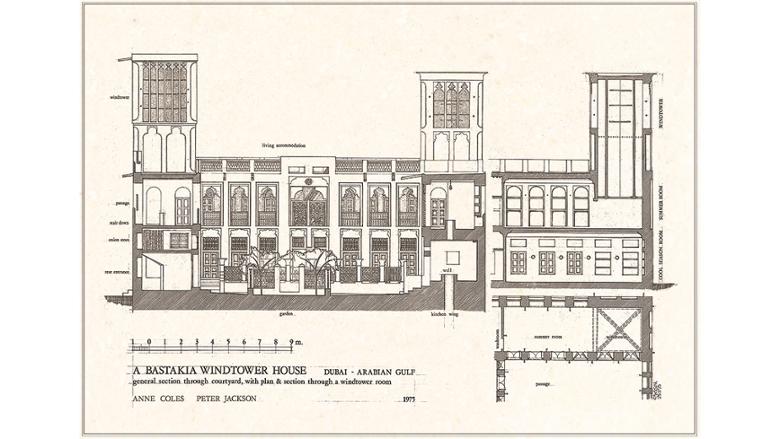

Her special interest led her to approach Peter, who by 1974 was now working full time for John Harris architects in London, to make a drawing of a windtower for the newly established Museum in the Al Fahidi Fort, during one of his visits to Dubai.

She provided Peter a letter to the Bukhash family who lived in a large home with a windtower in Al Bastakiya – the protagonist of a monograph that featured an architectural survey of the Bukhash house, and a description of both its history as well as family life.

“When I first saw the house I was fascinated because it was so different from any building I had seen in Britain. Everything about it was different – the materials, the way it was put together. I learnt a lot. I had never surveyed or made measured drawings of a historic building before. It was an academic assignment for my own interest and personal development.”

Over a span of 12 months, Peter completed the measured drawings in London in his spare time, while working with John Harris and simultaneously preparing for his final professional exams. “I suppose my historic architectural expertise all started with the making of that survey.”

In 1975, in collaboration with Anne, Peter produced a short monograph – A Windtower House in Dubai, published by Art and Archaeological Research Papers, AARP. Peter then moved on, to work in Zambia, and later Zimbabwe.

During his 26-year sojourn in southern Africa he launched an architectural partnership in Zimbabwe, where he also held the role of Historic Buildings Advisor to the City of Harare. His practice undertook work all across Zimbabwe, in the poor rural areas as well as in Harare, as well as projects in Botswana and Mozambique. His tryst with the UAE, however, would continue when he came back to the country in 2002.

An opportune meeting with architect Rashad Mohammed Bukhash played a key role at this juncture. Then Head of the Historic Buildings Section in Dubai Municipality, Rashad rekindled an association with Peter that he had never forgotten. Rashad was only 13 when he had first met Peter in the house built by his grandfather, Mohammed Sharif Bukhash, from 1924 onwards. His time spent helping the young architect at the time inculcated a lifelong love for historic buildings and architecture in Rashad, who would go on to establish – and continues to chair – the UAE Architectural Heritage Society. All this stimulated by the enthusiasm of a young British architect from a faraway land who was seeking to understand the architectural nuances of a different and fascinating culture.

The birth of a book

This common love for history, heritage and architecture serendipitously wove together to become the catalyst for a prodigious book – Windtower, that had started as the story of a single house, to become the story of an entire community and a former way of life.

The first edition was dedicated to the present and future children of Al Bastakiya. “We would now like to extend this dedication to include the memory of those friends we made in the community and who are no longer with us,” the authors explain in the introduction to the book.

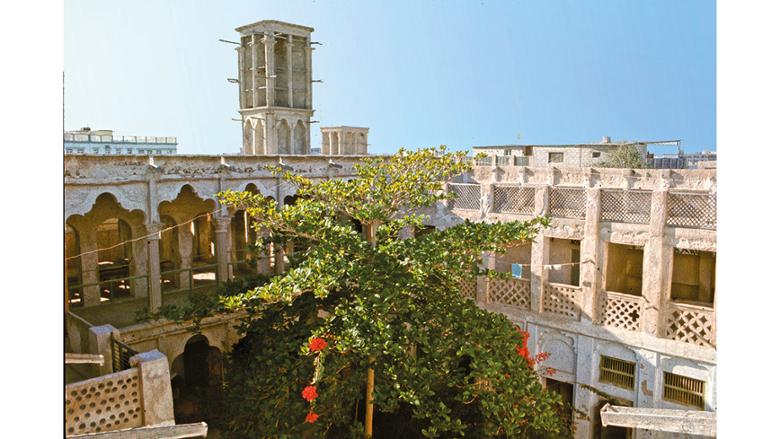

Al Bastakiya, located near Dubai Creek, is one of the oldest standing residential areas of Dubai, established from around 1900. In 2012, this locality was renamed Al Fahidi Historical Neighbourhood by His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, after the nearby Al Fahidi Fort. With the encouragement of Rashad, Peter and Anne began work collating their existing material on Al Bastakiya and the Bukhash house survey, and to now extend their study to include six other remaining houses and the Bastaki families who had lived in them.

“We expanded the subject to cover family life, how the buildings were used, especially the women of the household. So the architecture became the core around which the personal stories in the book could be told. It was a tremendous multi-disciplinary collaboration between Anne as a social geographer and myself being an architect,” says Peter.

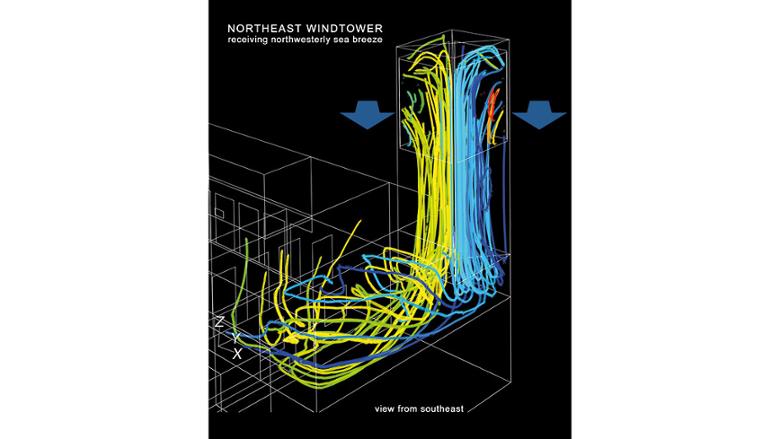

The next step was to find out whether windtowers had really worked sufficiently to offer effectively cooling in summer. To help on this, they received generous support from Ian Jones of Vipac, an Australian environmental testing laboratory, who at the time was working on the Burj Khalifa, in physically recording, and then analysing the climatic efficiency of traditional windtowers.

“I asked him how much it would cost him to do proper studies on the windtower and if he could give us a quotation so that we could try and find a sponsor to cover it. He never got around to giving us the quote, simply just becoming an enthusiastic member of our team, equally fascinated by our subject. He made temperature readings and surveyed three different wind towers through a full year, taking back this information to their lab in Port Melbourne, where it was combined with wind tunnel testing of a transparent scale model of the Bukhash house in Sydney, where computational models were developed, and in Singapore where the resultant comfort levels could be assessed.

“The conclusion is, as you will find in the book, that windtowers worked very efficiently during hot summer afternoons, creating sufficiently comfortable conditions for people resting, which is exactly what people did every afternoon. They would sit on cushions around the sides of the room, where much of the air flowed around, assisting evaporate perspiration, thus countering the heat. Windtowers created comfortable conditions, otherwise not achievable until the coming of electricity, through fans and air conditioning,” Peter says.

The book explains at length the intriguing seasonal upstairs-downstairs migration within the windtower houses to suit the summer climate conditions of the region. In their account of how these houses functioned, they recognised that women and children spent more time in the house than men, making efforts to reflect the perspectives of women who were “traditionally much less visible than men”.

The original book was greatly supported by those older members of Al Bastakiya families, and who generously shared their personal memories, together with the inherited stories of earlier generations.

“It’s been a long journey. A special quality of our book is that including Anne’s work from the late 1960s, it represents research undertaken over more than 50 years, thus covering more than three generations of family life. One of the great motivations of the first edition of the book was to capture memories of the last generation that had actually lived in the houses. It has been an enormous privilege to have touched the heart of the community over such a long period of time,” adds Peter.

Road bumps

Challenges were part of the journey too, as with most things. One of the earliest issues that Peter faced was to balance his full-time work, with a research project he was passionate about, while at the same time completing his university studies to qualify as an architect.

For the larger book, getting the stories right was demanding, especially the cross-checking of an enormous amount of information collected through interviews, to ensure its correctness, and then distilling this into an accessible text. Then for the new edition, the interviews could not be done face-to-face during the recent pandemic, rather being recorded on-line, for which new techniques needed to be learnt.

“When the subjects first spoke about their lives they wouldn’t always want all the information that they felt maybe too private or sensitive to be published. The special thing about the new edition is that it wasn’t the authors or publishers that drove it, but rather the demand came from the community itself.

“In fact, a local body, Al Bastakiya Cultural Centre, was formally established to become the collecting house for local history, and in particular to support the republication of Windtower, including an Arabic edition currently in preparation. Families that hadn’t been involved in the previous edition were enthusiastic to contribute, so an entirely new chapter has been added – and of course there has been a further 15 years of new developments since 2007,” he said.

Over the years, Peter and Anne have lost most of their older contributors, some of them having become dear friends, but have also met new ones, within a younger generation keen to participate and have their family stories told.

This project has been an enormous privilege – because in a way it is no longer our book, it is theirs, and the generations to follow.

Blending the old and new

“Today, some architects are interested in historic buildings, others consider themselves purely modernists. I personally thrive on both – and am most delighted when new and old are really successfully integrated. For example one of my favourite places is the Museums Island in Berlin, where there is a fantastic juxtaposition of both contemporary and classical architecture. To weave them together and make them work meaningfully together in the present is very special, and not easy to achieve. I have been privileged to work with Sharjah’s architectural heritage and especially the souq, which I still remember from my first visit in 1974.

“It doesn’t matter if architecture is old or new – what matters is does it work, what can you learn from it, what does it tell you about the past, what does it tell you about communities, about the people who built it. The more you look at it, you realise it is very rich, and that is one of the things that the Bastakiya studies that have shown me – that architecture is really a skeleton upon which the muscles and flesh of the stories of individuals, families and community can be told.”

As much as it pleases him to see an increasing number of restoration projects and younger architects involving themselves in conservation, the rapid advance of urban infrastructure and low-density development across the natural desert concerns Peter.

“The desert is being developed and lost – I watch it spreading, seemingly uncontrollably. The desert will become an ever increasing important future resource, especially for a rapidly expanding and growing population. This saddens me. We need to be building much more dense, compact and sustainable developments – and urgently respond to the green challenge.”

Words of wisdom

He suggests for student architects that it is really well worth looking closely at an old building, in order to get an understanding of how it was constructed, and how might have been used, whether such a study might be part of their course or not, as he did the Bukhash house nearly 50 years ago.

“From closely studying historic buildings you can learn an enormous amount. It might not be directly relevant to the new buildings you are working on but it will offer an understanding of what happened in the past, when vernacular buildings weren’t designed by architects but by experienced masons and the families themselves. They are usually very sensitive responses to what the place and environment as it was in those days, with experience learnt over generations passed on from father to son,” he explains.

Secondly, he believes that architects focus too much on buildings as single objects and pieces of art to feature in glossy magazines, rather than considering the important spaces we all use between the buildings – how buildings relate to each other, how people use this space, and for structures to be sensitive and considerate of their neighbours in making more harmonious urban space.

“The design of urban space between buildings is equally important as that of the buildings themselves. And we as architects need always to be mindful of maximising inclusivity in our designs, making buildings more accessible and welcoming to those with disabilities.”

In his role in Sharjah Government since 2007, Peter has been closely involved with numerous important architectural, historic and environmental projects, including the recently opened Sharjah Safari, Kalba Mangroves Visitor Centre, Buhais Geology Park, Al Hefaiyah Mountain Conservation Center, and the Sharjah Islamic Botanical Garden (a personal favourite). He is currently looking again at Sharjah Souk and its relationship to the creek waterfront, and projects with Sharjah Museums.

Windtower, The Merchant Houses of Dubai by Peter Jackson and Anne Coles is published by Medina Publishing.

Read more