The Sharjah model: ‘We must decolonise architectural thought’

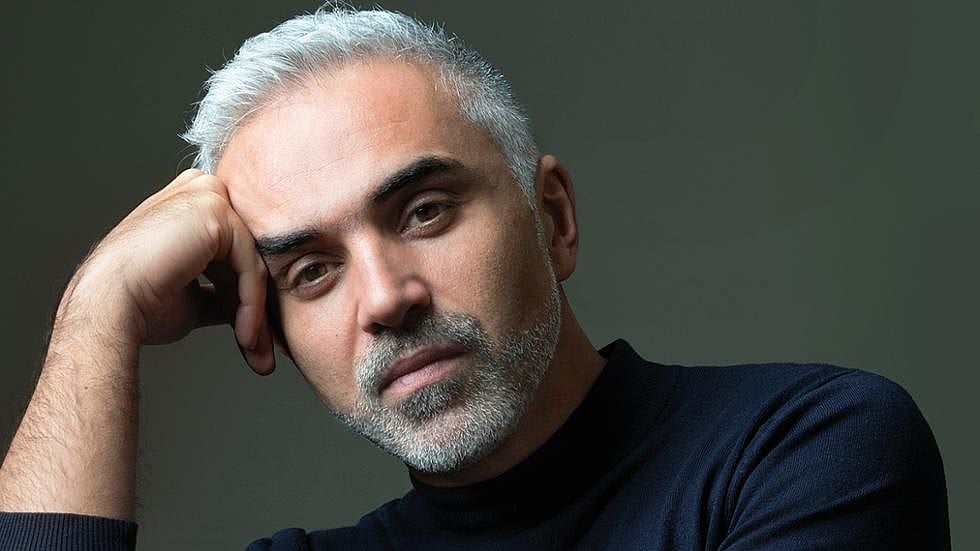

The Sharjah Architecture Triennial, on until February 8, explores the role of architecture in tackling climate crisis while also rethinking sustainable alternative modes of existence, Adrian Lahoud, the curator, tells Anand Raj OK

Adrian Lahoud firmly believes that architecture and climate change are intrinsically linked. The dean of Architecture at the Royal College of Art in London and the curator of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial that began last month in Sharjah feels that just as architecture shapes our interaction with the world and all living beings, so too does it hold a pivotal role in addressing climate change. ‘But to harness this potential, we must dismantle the extractive and exploitative models that currently dominate architectural practice,’ he says, in an exclusive interview with Friday.

The inaugural edition of Sharjah Architecture Triennial with the theme ‘Rights of Future Generations’ was opened by His Highness Dr Shaikh Sultan Bin Mohammad Al Qasimi, Supreme Council Member and Ruler of Sharjah. Billed as the foremost platform for architecture and urbanisation in the Middle East, North and East Africa and Southeast Asia, the Triennial, which is on until February 8 next year, will discuss the building environment in the region while offering a regional perspective to architecture.

It will also support research into the relationship of the urban environment within its complex social, economic and cultural contexts.

Among other areas that will come up for discussion are Sharjah’s rapid urban development amid historical transformations, ongoing cultural gatherings, environmental challenges as well as future aspirations.

Apart from leading architects from the region, anthropologists, researchers, performing artists and policy makers will be attending the Triennial, which will also explore the role of architecture in combating climate crisis, while rethinking sustainable alternative modes of existence.

Among key speakers are Dalal Alsayer from the University of Pennsylvania, Samia Henni from Cornell University, and Marina Tabassum, the founder of Marina Tabassum Architects and the 2016 winner of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Adrian, who is looking forward to the conversations that will ensue at the event, is convinced Sharjah is the perfect site for the Triennial.

Known for his post-colonial nation-building projects and climate research in the context of the Global South (low and middle income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean), the urban designer and researcher underscores the emirate’s long history of trade, not to mention a vibrant, multiethnic community. Sharjah, Adrian says, boasts historic monuments and structures that coexist seamlessly with modern contemporary buildings. Some of them will be showcased during the Triennial. Keeping in mind sustainability and with a keen eco-sense, two decommissioned public buildings – The Al Qasimiah School and the old Al Jubail vegetable market – both leading examples of the 1970s and ’80s architecture, are the venues for the event’s exhibitions. The Triennial will also showcase other examples of the 1970s and 80s architecture visible in many areas across Sharjah.

Excerpts from the interview with Adrian Lahoud...

You have been exploring the co-existence between high density development and historically significant inner city areas. It’s an issue most developing cities, particularly in this region, are facing. What are the challenges and how do we go forward with development without destroying our heritage and culture?

This is certainly a topical conversation, not only in the Gulf but across the wider Global South. We must critically interrogate our current approaches to high density development, and its intergenerational effects. This means not only questioning its effect on the legacies of past generations – looking at the threat it poses to historically significant areas – but also its effect on future generations, calling into question the environmental repercussions.

The theme of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial’s first edition, Rights of Future Generations, gives a platform to this intergenerational sensibility. Sharjah’s unique mixture of historic buildings and modern planned suburban neighbourhoods offers a fascinating context for considering these questions.

One way Sharjah deals with the challenges you describe is through a commitment to the adaptive reuse of buildings. This not only preserves structures of historical interest, but also offers an alternative, environmentally conscious model of development that works against extractive architectural methods.

The Triennial’s two main venues are decommissioned public buildings – the old Jubail vegetable market and the newly renovated Al Qasimiah School – both of which are leading examples of Sharjah’s 1970s and 80s architecture.

Climate change is another issue high on your agenda. How can architecture help?

Architecture and climate change are intrinsically linked. As architecture shapes our interaction with the world and all living beings so architecture holds a pivotal role in addressing climate change. But to harness this potential, we must dismantle the extractive and exploitative models that currently dominate architectural practice.

What five pointers can you suggest to architects to ensure their designs/plans are sensitive to climate change?

1. Limit extractive activity. Where possible, consider how we can thoughtfully readapt existing structures.

2. Learn from indigenous perspectives that have often worked harmoniously with the environment for millennia.

3. Decolonise architectural thought. Western models of development that have come to dominate architectural practice have led us to this point of ecological collapse. Seek alternatives.

4. Work with the natural world; not against it.

5. Always consider the rights of future generations – what environmental legacy are we leaving them?

You have often spoken about the importance to shift the focus away from individual rights to collective rights when viewing architecture from the perspective of future generations. Could you elaborate on that?

I believe current architectural practice does not take a sufficiently intergenerational approach to development, failing to consider the collective rights of unborn generations. In fact, the theme Rights of Future Generations emerges from international humanitarian law in the 1970s. At that time, there was a recognition of mass environmental destruction, which led people to question what the rights of future generations should mean. This question is especially pertinent now that we have reached a point of global climate crisis. The danger is that the less we do now, the more future generations will have to do – but under far more extreme and challenging circumstances. We are at a point of ecological collapse and one fact must not be overlooked: that the sites, regions and populations most immediately and irreversibly threatened by climate change are the same ones that face regimes of global socio-economic extraction and exploitation. The rights of collective future generations are in our hands, and architecture must take responsibility for the impact that our current extractive, exploitative architectural practices will have.

The Triennial is expected to challenge ‘pernicious’ Western views of Asian, African and Middle Eastern architecture. What exactly are those views and how can we attempt to set that right?

Western architectural paradigms have prevailed for too long. Traditionally seen to offer sophisticated models of development, they have been applied all over the world, in a large part due to colonialism, eclipsing alternative and local modes of existence. This has had damaging effects across the Global South – as Asian, African and Middle Eastern architecture has made way for Western models that are often ill-adapted to the locations in which they have been constructed. In attempting to set this right, I believe that we must decolonise architectural thought.

Our history offers us myriad examples of alternative social orders, of relationships between humans and other beings that evolved according to various beliefs and practices. Through these examples we might understand our agency and relationship with the world differently.

One of the ways to change is to overturn Western views on architecture and urbanism. How easy is that?

This will be a challenge, but one that I believe architects have a responsibility to undertake. Across the world, we are presented with alternatives to Western models. We just need to pay attention to them. The Sharjah Triennial is particularly exciting in this regard as it is the first international platform on the architecture and urbanism of the Global South.

Providing a much-needed space to critique existing architectural practice, the Triennial deliberately targets an emerging generation of architects drawn from across the Global South and their diaspora, particularly in response to the unique circumstances faced by architects, scholars, planners and artists in a postcolonial Middle East, North and East Africa, South and Southeast Asia.

There is a concept within architecture that the environment is a threat and we have to be protected from it. But not all societies see their relationship to the environment in the same way….

Yes, I believe that this concept is at the core of architecture’s struggle with the climate crisis. There is a prevailing, Western ontological distinction between humans and the rest of the natural world. This distinction is harmful in that it views architecture as a shelter from the environment, which justifies extractive activity that is detrimental to the environment.

However, as you say, not all societies see the world this way. There are examples around the world, particularly with indigenous peoples, where the boundary between humans and nature is perceived in a much more fluid way. The Triennial offers a unique platform to these alternative belief systems, considering how we might live more harmoniously with the environment.

Western architecture, some believe, has a certain condescending attitude towards architecture from Africa, Asia and the Middle East. How did that come about and how has that affected designs in the region?

The architecture of Africa, Asia and the Middle East has often been obscured by Western architectural models that have been adopted in these regions, serving as a physical manifestation of the effects of colonialism. This attitude is visible in the architectural landscape of the Gulf, often envisaged by Western architectural firms. That is why the Triennial attempts to decolonise architectural practice, targeting a new generation of architects from across the Global South.

We have deliberately selected the Al Qasimiah school as the Triennial’s headquarters. The repurposed venue was originally designed in the 1970s by regional architectural firm Khatib & Alami. A prototype for architectural development in Sharjah in the 1970s and 80s, the choice of venue embraces a model that emerged within the region and has been successfully adapted to offer a much-needed, permanent resource for architects across the Global South.

So should we be insulating ourselves from the environment around us? Shouldn’t we be more inclusive?

This goes back to my comments on the Western ontological distinction between humans and the natural environment. As I said, I believe this distinction is detrimental because it considers architecture to be about insulation or separation from the environment. I believe architects have a responsibility to protect not only humans, but also the natural world. That is why the Triennial hopes to raise awareness of alternative belief systems and modes of existence – ones that allow interacting and living with the environment, rather than dividing ourselves from it.

You promise to put voices of young people or even the next generation at the centre of the Sharjah Triennial. What are the voices that need to be heard? What are the statements you think the next generation are – or should be – worried about apropos architecture and urbanism?

Integral to the theme Rights of Future Generations is a commitment to the young people and future generations who will inherit the effects of the decisions we make today, of course. It’s also about looking back and learning from the past, taking a holistic viewpoint in this notion of intergenerational legacy.

The Triennial seeks to empower people to enter into meaningful discussions about these ideas. At the moment, we are seeing an amazing outpouring of feeling from the younger generations globally who are facing up to the daunting reality of climate crisis. We hope to build on this momentum to encourage impactful engagement with the potentially pivotal role of architecture and urban planning.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.