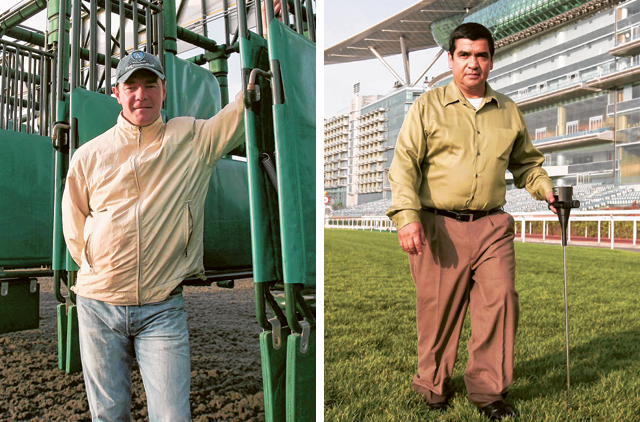

- Shane Ryan: THE STARTER

Aside from the time it takes to pour an Irishman's favourite beverage, 90 seconds is also the allowance Dubai World Cup starter Shane Ryan gives himself to load and release 16 horses from the gates before the start of a race.

The 38-year-old, who's a long way from his native Tipperary, Ireland, has it down to a precise science. No one horse should go over a 10-15 second individual loading time.

Talk of it going wrong is tantamount to "tempting fate" says Ryan. The 1993 Grand National "race that never was" where the event of the year was run to completion and won by a 50-1 outsider Esha Ness, but then ruled void due to a false start, is a thought quickly dampened by a superstitious Ryan.

Read in-depth coverage of Dubai World Cup

Blog: Behind-the-scenes at the Dubai World Cup

But it serves to demonstrate just how crucial his role is to a $10 million (Dh36.7 million) race watched worldwide by an audience of similar magnitude.

Pressure

So is it stressful? "No, the people make it stressful not the horses," said Ryan who has a crew of 16, an assistant, two vets, a farrier and ambulance crews on standby at the gates.

"Things can go wrong yes. These are animals with minds of their own and each horse will think and react very differently — but the pressure brings out the best in you."

It's Ryan's job to do his homework on every horse coming into the UAE for every race of the season not just the big one. He has starters from all over the world on speed dial and can formulate an unwritten dossier on each horse or watch old videos so that he can customise their load to make it as quick and painless as possible.

Reserve energy

"You don't want the horse to exert all its energy just on getting into the gate because it won't have enough left in the tank to perform, similarly you don't want the other horses standing idle in the gates to long while one plays up as they'll lose their bite — the idea is to reserve their energy and release it quickly," said Ryan.

Ryan, a former jockey in England, added with pride: "Elsewhere in the world they use blindfolds to get the horse in, but here we tend to work with them a bit more."

Having done this job for the last seven years being at the start obviously means Ryan doesn't have perhaps the best vantage point from the back of a horse, but his memories are still sweet nonetheless.

"My favourite horse to have won was Curlin in 2008 ridden by Robby Albarado. The way the champion in America came here and really stamped his authority was inspirational."

- Javier Barajas: THE TRACK SUPERINTENDENT

When he was 11 years old, Meydan track supervisor Javier Barajas, now 49, saw Secretariat come out of the tunnel at Arlington where his father was the turf foreman. He also witnessed John Henry win the first Arlington Million, a horse that "looked like a mule but ran with all its heart," according to Javier.

Horseracing is in Barajas' blood and dealing with "awesome horses" is nothing new to him. On the flipside to this, it's the responsibility of appeasing all of the world's top horses in the richest race on earth with fair and equal conditions that keeps Javier up at night in the run up to the $10 millon Dubai World Cup in his role of preparing the racing surface.

Harder surfaces

"The Japanese and American horses favour harder surfaces while the English and Irish like it soft. My job is to find a happy medium so that it's a level playing field for all," Barajas explained. "It's pretty difficult, they all want it to their own liking, there's $10 million on the line after all — but at the end of the day the only one that will think I've done a good job is the one that wins," said Javier, originally from Mexico.

Barajas, who with his assistant Inderjit Singh oversees the turf and Tapeta All-Weather tracks must also control the speed of the surfaces.

"When hot the surface has a tendency to get lose and go slow but if too cold its firm and thus faster. Trainers don't like it too fast because it gets dangerous. Our priority is safety," said Barajas.

With temperatures and conditions ever changing even throughout the evening of one race night, with the first race at 4.45pm and the last at 9.40pm, Javier's job isn't over until it's over.

In a country like the UAE where the difference between hot and cold can be suddenly quite vast it's an unprecedented task for Javier even with 35 years experience in the US.

So how does he manage and control speed and density of these 1,750-2,400 metre tracks with just 30 minutes between races?

"There are various methods. We can rip it or roll it with the germinator which trails behind a tractor or we can water it if it gets too hot, we constantly monitor temperatures over the course of an evening — but changes are fractional, otherwise it leads to problems so we really end up playing it by ear."

In the build-up to World Cup night and throughout the festival Barajas is at the track every day for morning trials and has constant interaction with jockeys and trainers airing any grievances or opinions on the conditions. But confrontation is rare as Barajas and his team are widely respected for their role in transforming the Meydan surface from a construction site to a world class track in just two months, in time for last year's first World Cup at the Meydan facility.

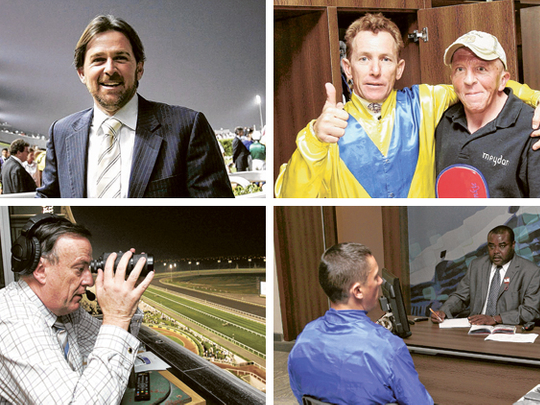

- Jason Wellings: THE VALET

"They stand on their silks," said head valet Jason Wellings when asked if any of the jockeys had strange pre-race rituals or superstitions.

Wellings would know. He's been privy to what's gone on in the jockey's room before and after a Dubai World Cup for the past five years.

It's his job to prepare and distribute silks, breeches, boots, saddles, socks and riding gear to all the jockeys for every race over the course of an evening and then take them back at the end of a night for cleaning to start all over again the next day.

He's with the jockeys at some of their most nerve-wracking moments leading up to the weigh-in before the race and has witnessed unadulterated joy and despair all in one room afterwards.

Quirks

But why do the jockeys ruin all his hard work by standing on clean silks?

"To get them dirty," said Wellings, 38, originally from Doncaster. "It's just your luck that if you have something new or clean its going to get ruined, you expect to fall off the horse, so you may as well get them dirty yourself to avoid that."

"It's mainly the Irish and English lads that do that, some of the lads just request their lucky saddle or whip — but everyone has their quirks," said Jason.

In charge of four other valets, Wellings splits the workload so everyone is responsible for the preparation of five jockeys each. He is also happy to have a certain Frankie Dettori among his crop of riders.

"Frankie has to be the biggest character in the weigh-in room, everyone knows him and he'll chat to anyone, he's worldwide. There's a lot of friendly camaraderie and banter before a race, some zone out, keep to themselves, you can see them going through their race in their head, but it's our job to break the ice, but with Frankie you don't have to try so hard.

One of Wellings' finest World Cup memories was when Dettori rode Electrocutionist to victory in 2006.

"It was so important for him it was the one race he'd never won and to have done it in the bosses' backyard was extra special — he went mad in the only way he knows how afterwards," he recalled.

He also valeted Robbie Albarado on Curlin in 2008 and witnessed the moment Kevin Shea discovered he had not won the 2010 World Cup, despite thinking otherwise. A photo finish between his horse Lizard's Desire, Allybar and winner Gloria de Campeao had put him second by a whisker.

"He was all happy thinking he'd won a World Cup then two minutes later he was told he hadn't, he was happy for a second but at the same time absolutely devastated — it was a real hard luck story."

Long after the celebration or commiseration has cleared, Wellings and his team are still in the weigh-in room collecting the gear back up and washing the equipment ready for next time. It's an effort that largely goes unseen.

"It's hard work but it's a good buzz — there's nothing like being in the weigh-in room on World Cup night watching them all prepare for what will be one of the biggest nights of their lives," he says.

- Gerard Bush: THE CHIEF STEWARD

History has thrown-up many examples of foul play in horse racing.

From scrubbing a horse's legs with soap suds to give the impression it's sweating — thus reducing its odds — to putting a sponge up the nostrils of a favourite or piano-wiring its mouthpiece.

Chief Steward Gerard Bush's job is to ensure the UAE maintains its 100 per cent spotless record in this regard.

Having upheld the latter for 13 years, the last eight of which have been spent in Dubai, Bush, 36, originally from Australia, explained: "Stewards are the ones entrusted to ensure all the rules of racing are adhered to by all industry participants in order to protect the integrity of the sport.

"The main issues we deal with on race nights is the interference in races. Other incidents that we deal with regularly are the use of the whip by the jockey during the race, conduct issues, issues related to the riding weight of a jockey, behavioural issues of a horse at the starting gate or during a race," said Bush.

Breach of rules

"If a rule is breached or an incident occurs that may lead to a rule being breached, then the stewards will hold an enquiry to determine if a rule has been broken and if so, will then determine an appropriate level of action to take."

Asked how many enquiries he has sat on in his career, Bush replied: "Enquiries can range from minor issues dealing with a horse's behaviour at the starting gate to more serious issues such as a horse testing positive for banned substances — the answer is too many to remember — this job certainly has its moments."

Speaking more generally about his widespread experience in the world of horseracing, Bush said: "Like any sport that has such high stakes there will always be a small minority of individuals who try to play outside the rules in order to gain an advantage for themselves and they do this with complete disregard for the damage they do to the good reputation of horseracing."

Admittedly having to take more of a backseat to the game given his responsibilities, Bush can still reminisce with fondness from his unique vantage point trackside.

"I was lucky enough to witness See the Stars win the Pre de l'Arc de Triomphe a couple of years ago and more recently Black Caviar - easily the best sprinter I've ever seen."

"As for World Cup night Heart's Cry winning the Sheema Classic in 2006 was fantastic to watch and the extremely close finish to the World Cup race last year was just as exciting."

Bush added of the future: "The World Cup has always held a significant position on the world racing calendar, but perhaps the transition from dirt to a synthetic tapeta surface at Meydan will make the actual World Cup race even stronger in years to come as more turf horses will now target that race."

- Yasir Mabrouk: CLERK OF THE SCALES

All the jockeys from all 15 Dubai World Cup races have had to pass through a certain no-nonsense Yasir Mabrouk.

In his role as senior clerk of the scales, the 44-year-old Sudanese has stared victory and defeat in the face of every jockey at every World Cup since its inception.

He'll talk as though its nothing special, but ask him to name who among his colleagues has achieved a similar attendance rate and it's a mere handful.

If he sometimes fails to recall the particular hue of agony or despair etched on every loser's grimace, the jockey themselves surely can't forget the plain blank stare that Mabrouk reciprocates, while weighing them back in.

His job, quite simply, for 22 years in Dubai has been to weigh the jockey and their equipment out and back in again after the race at the same and correct precise measurement.

"I don't like to get too friendly with them [the jockeys]. I keep my distance. As an official there's the whole thing of integrity and credibility to uphold. If you lose that you've lost command," said Mabrouk.

Quiet moment

He may have been the only person to have shared a brief quiet moment with all 15 winners, since dismounting; with media, friends, trainers and loved ones flocking to the latest champion, but with Mabrouk weighing them up top-to-toe it's just another race — they can't expect too much adulation from him.

"The winner is always last in and he'll sometimes take up to 15 minutes to come back to me after the race. I remember Richard Hills on Almutawakel in 1999, it took forever to bring him back, he was so busy celebrating," said Mabrouk.

"Jerry Bailey has won it the most times [1996, 1997, 2001, 2002] but he watches the way he reacts carefully, I've never seen him like Frankie [Dettori], who after his flying dismount is all over the place with excitement."

Mabrouk adds, "Of course horses come here with big reputations and jockeys are under a lot of pressure. When they don't perform it can be a very edgy atmosphere, but I try to absorb some of the anger from the also-rans if I can without getting too close."

The only time a weigh in has got personal is with the UAE's sole professional jockey Ahmad Ajtebi, a former child camel jockey, whom Mabrouk helped guide in his other role as Master of Apprentices (he's also an Arabic-English translator), from obscurity to the ranks of Dettori's number two.

Under Mabrouk's father-like wing, Ajtebi went on to win the Dubai Duty Free and Sheema Classic in 2009 with Gladiatorus and Eastern Anthem, a prospect that brought more than a tear to Yasir's eyes.

No memory serves greater however than Cigar's win at the inaugural World Cup in 1996, for Mabrouk. "Cigar came here having won 16 races on the trot with the eyes of the world upon him. His win raised the profile of the event no end, as every winner has, but few winners have been as prolific and reputable as Cigar."