Political obsessives tend to ignore the voters

A campaign cannot make people feel something they do not already feel

Another word for “profession” is “ghetto”. people who work in the same field develop their own codes and slang. They sleep and socialise with each other. Without intending to, they seal off their world from uncomprehending outsiders. This is true of architects and personal trainers, estate agents and medics. It is a byproduct of specialisation and there is nothing sinister about it.

The difference with politics is that professional insularity inhibits performance. The central task of anyone in politics — MP, adviser, commentator — is to see inside the mind of the average voter. But the average voter is indifferent to politics. So anyone who is absorbed in the democratic process is badly placed to understand the demos itself. An obsessive violinist can be a great one. An obsessive politico will make analytic errors.

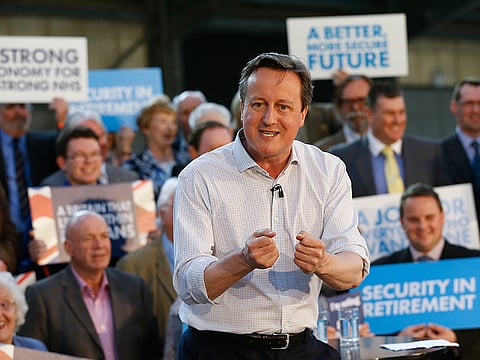

Recent events in the United Kingdom general election campaign that were expected by people in politics to be vote-shifting include: David Cameron’s evasion of any televised debates; his subsequent capitulation to the idea; the broadcasts themselves; his self-imposed deadline of only one more term as prime minister; the budget. The polls remain as still as mountains. We thought people were paying attention so we over-analysed events that actually washed right over them.

The biggest politico error of the moment is to curse the flatness of the campaign itself. The theory goes that voters are ravenous for visionary politics. Instead, they are offered dry campaigns curated by parties that have become professional to a fault. This is only half right. The campaigns are sterile. The Tories tout their economic bona fides and nothing else, like cyborgs programmed with one sentence of spoken English. The opposition Labour party is cautious, too: the first draft of its manifesto, all flowery talk of community empowerment, has been gutted and rewritten by advisers to the leader, Ed Miliband.

Voters are unsatisfied with the parties’ offerings. But what is the evidence that they want more romance instead? Why are some Tories so sure that bolder ideas and fizzier rhetoric would add votes, not lose them? Why do excitable Labour types think that “letting Ed be Ed” will help?

Swing voters worry about the Tories’ blueprint for a smaller state and Labour’s taste for leveraged spending. In other words, their grievance with the main parties is actually their excess of vision not their lack of it.

Grand programmes couched in vivid language move only people already interested in politics. For most people, whose principal ideology is loss aversion, this mode of politics is irrelevant at best and scary at worst. If even a slogan as drab as “long-term economic plan” strikes some swing voters as code for prolonged austerity, something fierier would have them groping nervously for their wallets.

Political obsessives misunderstand politics. A campaign cannot make people feel something they do not already feel. It just uncovers the general will, of teasing out what is already there. The political class still disparages last year’s campaign against Scottish independence for its arid focus on economic risk. Yet, all the research says it was well judged: Undecided Scots were emotionally in favour of independence but doubted its viability. The campaign brought out those doubts.

Political obsessives misunderstand their own country, too. Even by western standards, Britain is extraordinarily evolved. It is decades into post-modernity. It is cynical, ironic, unimpressed. It seems to be inoculated against fevers of radical thought. The British raise a derisive eyebrow at anyone who gets too worked up about anything; enthusiasm is the last taboo.

Cameron and Miliband cannot pretend they are pitching to a country of hysterical politicos aflame with a love of ideas. The soul of Britain does not reside in Speakers’ Corner, but in Ikea car parks and middling gastropubs on weekend afternoons. There is no politics in these places, just quotidian life.

And this is a good thing. Political apathy is a mark of civilisation. Boring elections are proof of national success. Politics is exciting in countries where the rules of the game are contested.

This week, it is 23 years since John Major won more votes than any party leader has managed before or since. His two-card trick was his milquetoast persona and a campaign that ground Labour down on the narrow question of tax. No magic, no poetry. The obsessives hated it. He called them the “upper one thousand of politics”, and made do with 14 million others.

— Financial Times