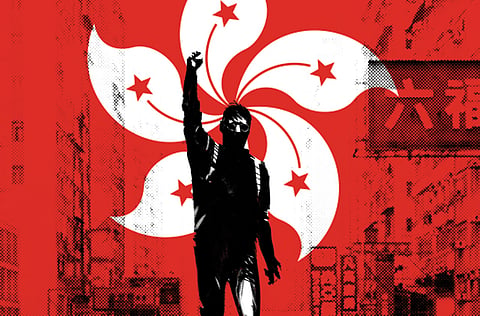

Hong Kong will never be the same again

Hong Kong will be politically volatile for years to come

As the high-stakes poker game between students and the Hong Kong government draws to a thankfully blood-free close, it is not too early to consider what lasting impact the pro-democracy protests will have on the former British colony.

To start with a conclusion, the outcome of the contest was predetermined. The students’ central demand that Hong Kong adopt “genuine” democracy was a nonstarter. Beijing had in late-August handed down its judgement, setting strict limits on Hong Kong’s election rules. That made it inconceivable it would bend to the students’ demands. If this was a poker game, it was rigged. Banker always wins.

True, “negotiations” between CY Leung’s Hong Kong administration and pro-democracy advocates will now take place. Yet, the city’s authorities have little leeway to negotiate. The best on offer is a system in which at least half the members of a nominating committee — at present just 1,200 people — select two to three candidates from which Hong Kong’s five million electorate can pick. There is no question of public nomination of candidates. No system will be permitted that could select for public ballot a radical, let alone anti-Beijing, candidate. If talks are to continue, the students will have to ditch some core principles.

So what did the extraordinary events of the past 10 days mean? At least three important questions are raised. First, will Hong Kong ever be the same again? Second, was anything achieved? Third, in retrospect, were the comparisons with Tiananmen Square overdone?

To answer in reverse order, analogies with Tiananmen Square were tempting, but misleading. As in Beijing in 1989, students led the protests, pitting their idealism against the flinty realities of a one-party state. But to start geographically, Hong Kong is a cramped, teeming city of skyscrapers with nothing comparable to a Tiananmen Square on which students could camp out for weeks or months. Even after a few days, protesters ran up against opposition from ordinary citizens resentful at losing time and money.

There were deeper differences. Hong Kong is still governed under the one-country-two-systems model. Although ultimately the students’ quarrel was with Beijing, their day-to-day struggle was with a local leadership with no stomach for a brutal crackdown. Hong Kong’s laws, too, protected the students. Their messages were transmitted by a free press and their leaders protected by independent courts. No Tiananmen-style massacre was ever plausible, though there could have been some deaths if police had been more heavy-handed.

As Jeff Wasserstrom of the University of California, Irvine, notes, there might be closer parallels with other student-led protests in Chinese history. In 1919, the May Fourth Movement did not end warlord rule, but it did force the resignation of officials, something that is still plausible in Hong Kong where Leung has become a focus of contempt and questions about business dealings.

Did the students achieve anything? The hard-hearted will say no, save a few billion in lost retail sales and tourist receipts. Yet, one does not need to be a sentimentalist to have been stirred by the sight of a new generation taking action in the cause of democracy. Tens of thousands of young Hongkongers have grown up politically almost overnight. Many have learnt important lessons about the power — and limits — of organised protest.

What of Hong Kong itself? This is, after all, a city that has come through turmoil before. Only 17 years ago, Britain handed it back to China. In 2003, an outbreak of Sars sent the economy into tailspin. Hong Kong has always recovered. Its place as Asia’s premier international financial centre is, for the moment, secure.

The rule of law that underpins that role has, on balance, been reaffirmed. Beijing needs Hong Kong almost as much as ever. China’s current account is closed, its brand of capitalism unsophisticated and its currency unconvertible. For Beijing, Hong Kong remains a vital place to raise capital, test its companies against global standards and experiment with the internationalisation of the renminbi.

Yet, the events of the past 10 days will leave a permanent psychological mark. Few can now doubt that Hong Kong is a Chinese city, subject, when push comes to shove, to Beijing’s rules.

Equally, though, few can imagine that the fundamental issues raised by the students are in any way settled. Hong Kong’s people know what a hollow form of democracy looks like when they see one. Many of them, especially the younger generation, want more. That means the city will be politically volatile for years to come. The Hong Kong as we know it - where business trumps politics and money trumps ideology - is gone.

— Financial Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox