We have let Arab Christians down

Let us not forget the critical role they played in revival of our collective identity

In 1516, when the Ottomans took over the Arab world, the Arab Christians became subjects of the Ottoman state, just like their Arab compatriots. However, they were considered as ‘second class citizens’ and while, as non-Muslims, they didn’t have to do military service, they had to pay tax to the state for protection and the freedom to practise the rituals of their religion.

The Arab world, which was under the rule of the Ottomans that ended in 1918, following the Arab Revolution and the defeat of Turkey in World War I, is the ancestral home of several Christian communities. In the Levant, they are divided into many religious communities, mainly the Rum Orthodox, Catholics, Armenians, Maronites, Protestants, and Copts in Egypt.

In Iraq, the main Christians sects are the Chaldeans, the Syriacs, the Armenians and Assyrians. All these sects have been here as old as the Christian faith itself, more than 2,000 years. In fact, the Iraqi Christians are credited with converting millions of people to Christianity in India and China through their travels to those countries to import silk and spices.

Arab national fabric

But that is not all the contribution of the Arab Christians. Their contribution to their homeland, the Arab world, was far more important and critical to the survival of the Arab identity, which at one point was faced with a real threat of obliteration under the strict Ottoman nationalist rule.

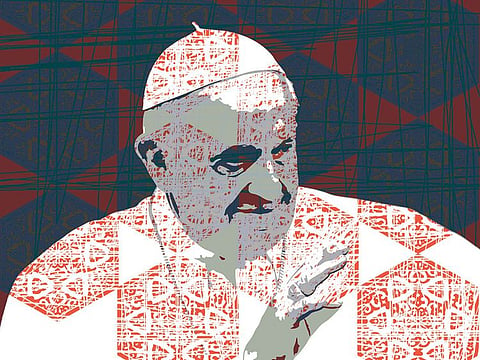

And as we follow the landmark visit of Pope Francis to Iraq, the birthplace of Abraham, the father of the prophets, we are reminded of the historic facts that we tend sometimes to forget when talking about the Arab Christians and how integral they are to the Arab national fabric. And how they played a leading role in preserving our collective identity when it was under attack.

In the four hundred years of Ottoman rule in what was called the Arab Provinces, the region was basically a backward place that lacked proper education, health system or a state structure. The most notable provinces, such as the Levant and Iraq, were mostly primitive farming societies that provided the Ottoman an unlimited human resource for their military ventures elsewhere.

The Ottomans were themselves until the late 18th century a traditional society resistant to change and modernity. One historian remarked that the only contact the Ottoman had with the outside world was on the battlefield.

Literary renaissance

As the state weakened in the 1800s and later years, there was much pressure on the Arab provinces and its peoples to pay more taxes while the rise of Turkish nationalism in later years threatened to eradicate other national identities among those ruled by the Ottoman, leading to a cultural crisis that sparked concerns among many educated Arabs, particularly the Christians.

Western powers had a couple of hundred years earlier struck a deal with the Ottoman State in which they put some of the Arab Christian community under their protection. They provided those communities with decent educational institutions, built more places of worships and hospitals.

For example, in 1585 the Vatican established a school for the teaching and preparation of Maronite priests in Lebanon. Those students, with the education and knowledge they gained in those institutions, began researching and publishing their own Arab heritage. It was some sort of literary renaissance. By the beginning of the 19th century, this movement reached Egypt and Iraq.

As the Arab cultural crisis deepened, cultural activities related to the Arabic language and the Arabic customs were organised, mostly by the Christian Arabs, in major cities such as Damascus and Beirut.

Call for unified Arab state

These forums called for national unity among the Arabs and aimed to repair the sectarian and cultural damage in those societies. They also called for ‘the liberation of the Arab homeland’ from Turkish rule and the establishment of a unified Arab state. Prominent among those who championed the cause were leading Christian intellectuals Boutros Al Boustany and Ebrahim Yazaji. The principal idea is that with its different faiths and sects, the Arab world cannot be united but through a secular identity, as Arabs.

Historian Waheeb Al Shaer notes in a paper published 2014 that the 18th century Lebanese cleric, Bishop Duwayhi of the Maronite Church, wrote to Muslim scholars in Damascus “appealing to them to look to their Christian brothers instead of looking to the religious association with the Turkish outsiders in Istanbul, stressing that the national common is stronger than the religious common and more promising.”

In the decades that followed dozens of social and literary clubs and association were set up by Arab intellectuals, Christians and Muslims that called for Arab unity and independence. Newspapers and magazines started to appear in the market. It is worth noting that the Arab world’s largest newspaper today, Egypt’s Al Ahram was founded in Alexandria in 1875 by two Lebanese Christian brothers, Beshara and Saleem Takla.

Collective feeling

These efforts succeeded in formulating an Arab collective feeling of a national identity that remains strong today. The 1916 Arab Revolt against the Turkish state was partly a result of the efforts of the early champions of Arab independence.

In the last century, Christian thinkers and politicians continued their vital contribution to the ideological formation of Arab society and had key roles in establishing pan-Arab movements. Among them were Antun Saadeh, a Syrian nationalist and promoter of the cultural cohesion of Greater Syria, Constantine Zuraiq, and George Habash, leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a historic figure in the Palestinian struggle for independence.

However, things have dramatically changed in the past few decades. For example, the Christian population in the Arab world declined dramatically in recent years: from 20 per cent of the entire Arab population in the early 20th century to six per cent in recent years. Historians point to low birth rate, emigration, and ethnic and religious conflicts as the main reason for the decline.

In Iraq, for example, the Christian communities were estimated to be between 1.5 and 1.8 million in 2003, prior to the US invasion of the country in that year. Now it is at between 250,000 and 300,000, making the Iraqi Christian diaspora far larger than the population of Iraqi Christians living in their own country.

Have we, the Muslim Arabs, let our Christian community down? Yes. As the terror groups went after them in recent years in Syria and Iraq because they are different, we stood idle. This might not sound politically correct, but Muslim Arabs haven’t moved a finger to protect our Christian brothers or help them fight the menace of Daesh and other extremist groups.

The departure of the Christians makes this region poorer culturally and socially, duller and a less interesting place to live in. But more importantly, we owe it to them to save their communities and help them stay in their ancestral land for they, for hundreds of years, carried the burden of saving our own identity and existence.

I hope the pope’s visit to Iraq will underscore this message too.