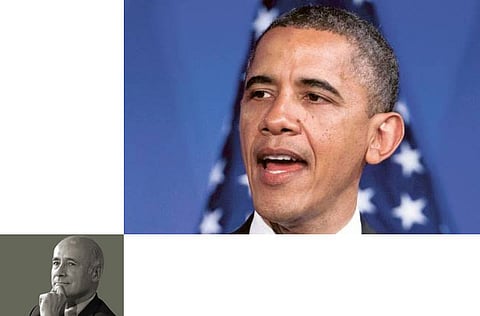

Obama’s foreign policy doctrine

US president has chosen to reduce America’s heavy military footprint global ly

Public-opinion polls in the US indicate a close presidential election in November. While President Barack Obama outpolls the Republican challenger Mitt Romney on foreign policy, slow economic growth and high unemployment — issues that are far more salient in US elections — favour Romney. And, even on foreign policy, Obama’s critics complain that he has failed to implement the transformational initiatives that he promised four years ago. Are they right?

Obama came to power when both the US and the world economy were in the midst of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Indeed, some of Obama’s economic advisers counseled him that unless urgent steps were taken to stimulate the economy, there was a one-in-three chance of entering a full-scale depression.

Thus, although Obama also inherited two ongoing wars, nuclear-proliferation threats from Iran and North Korea, and the continuing problem of Al Qaida’s terrorism, his early months in office were devoted to addressing the economic crisis at home and abroad. His efforts were not a complete success, but he managed to stave off the worst outcome.

Obama’s rhetoric during his 2008 campaign and the first months of his presidency was both inspirational in style and transformational in objective. His first year in office included a speech in Prague in which he established the goal of a nuclear-free world; a speech in Cairo promising a new approach to the Muslim world; and his Nobel Peace Prize speech, which promised to “bend history in the direction of justice”.

In part, this series of speeches was tactical. Obama needed to meet his promise to set a new direction in foreign policy while simultaneously managing to juggle the issues left to him by George W. Bush, any of which, if dropped, could still cause a crisis for his presidency.

Nonetheless, there is no reason to believe that Obama was being disingenuous about his objectives. His worldview was shaped by the fact that he spent part of his youth in Indonesia and had an African father.

Activist vision

In the words of a recent Brookings Institution book, Obama had an “activist vision of his role in history”, intending to “refurbish America’s image abroad, especially in the Muslim world; end its involvement in two wars; offer an outstretched hand to Iran; reset relations with Russia as a step toward ridding the world of nuclear weapons; develop significant cooperation with China on both regional and global issues; and make peace in the Middle East”. But his record of achievement on these issues has been mixed.

“Seemingly intractable circumstances turned him from the would-be architect of a new global order into a leader focused more on repairing relationships and reacting to crises — most notably the global economic crisis,” the report continued. And while he eliminated Osama Bin Laden and weakened Al Qaida, some counterterrorism policies ended up undercutting his appeal in places like the Middle East and Pakistan.

Some of the half-empty glasses were the result of intractable events; some were the product of early naiveté, such as the initial approaches to Israel, China, and Afghanistan. But Obama was quick to recover from mistakes in a practical way. As one of his supporters put it, he is a “pragmatic idealist”.

In this sense, though Obama did not back away from rhetorical expressions of transformational goals regarding such issues as climate change or nuclear weapons, in practice his pragmatism was reminiscent of more incremental presidential leaders like Dwight Eisenhower or George H. W. Bush.

Despite his relative inexperience in international affairs, Obama showed a similar skill in reacting to a complex set of foreign-policy challenges. This was demonstrated by his appointments of experienced advisers, careful management of issues, and above all, keen contextual intelligence.

This is not to say that Obama has had no transformational effects. He changed the course of an unpopular policy in Iraq and Afghanistan; embraced counter-insurgency tactics based on less costly uses of military and cyber power; increased American soft power in many parts of the world; and began to shift America’s strategic focus to Asia, the global economy’s fastest-growing region.

With respect to Iran, Obama struggled to implement United Nations-approved sanctions and avoid a premature war. And, while the Arab Spring revolutions presented him with an unwelcome surprise, after some hesitation he came down on what he regarded as the side of history.

In a new book, Confront and Conceal, David Sanger describes what he calls an “Obama Doctrine” (though he faults the president for not communicating it more clearly): a lighter military footprint, combined with a willingness to use force unilaterally when American security interests are directly involved; reliance on coalitions to deal with global problems that do not directly threaten US security; and “a rebalancing away from the Middle East quagmires toward the continent of greatest promise in the future – Asia”.

The contrast between the killing of Bin Laden and the intervention in Libya illustrates the Obama Doctrine. In the former case, Obama personally managed a unilateral use of force, which involved a raid on Pakistani territory. In the latter case, where national interests were not as clear, he waited until the Arab League and the UN had adopted resolutions that provided the legitimacy needed to ensure the right soft-power narrative, and then shared the leadership of the hard-power operation with Nato allies.

The long-term effect of the Obama Doctrine will require more time to assess, but, as he approaches the November election, Obama appears to have an edge over his opponent in foreign policy. Obama has not bent the arc of history in the transformational way to which he aspired in his campaign four years ago, but his shift to a pragmatic approach may turn out to be a good thing, particularly if voters continue to have doubts about the economy.

— Project Syndicate, 2012

Joseph S. Nye is a professor at Harvard University and the author of The Future of Power.