Libya: Colonialism and autocracy

Hub Editor Najla Al Rostamani writes: Libya has an ironic history, albeit not very different from that of other Arab countries.

1) Colonial Era

Libya was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. During the 16th century, three provinces were brought together as a single entity: Tripolitania (Tripoli), Cyrenaica (Barqa), and Fazzan (south west of the country). In the 1800s, the Al Sanussi dynasty became a powerful force in the country, spreading its influence across all cities.

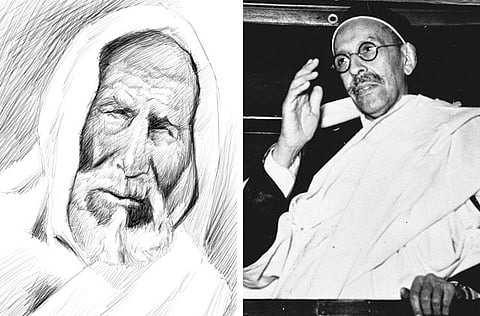

Just like neighbouring Arab countries, Libya also suffered from the colonial era. In the years 1911-12, Italy invaded the country, ruling it with an iron fist. The Libyan people launched a staunch resistance movement against the Italians — one that was admired by all Arab resistance movements at the time. The resistance was made up of a grass roots movement whose outreach was as vast and wide as the Libyan society, and was led by the Al Sanussi family. One of the most memorable names in Arab history is Omar Al Mukhtar (pictured)— the legendary freedom fighter. But by 1929, the tide turned in favour of Italy as its campaign was supported by modern artillery. Eventually, this particular colonial era came to an end in 1931.

The shift in the world's balance of power in 1942 shaped Libya's fate. With the beginning of the Second World War, the Allied forces drove the Italians out of Libya. The country was then divided among them. Tripolitania and Cyrenaica fell under British rule while Fezzan came under French control.

2) Independence

In 1949 Libya attained its independence. Idris Al Sanussi (pictured) became the leader of a newly independent Cyrenaica. In the same year, the United Nations said that independence would be granted within two years to the newly formed entity.

Over the next few years, Libya's leadership took political steps towards building a nation that had just emerged from long years under colonialism.

In 1950, a national assembly convened in Tripolitania at which Al Sanussi was designated the king. The following year, a new constitution was introduced. By the end of 1951, King Idris declared the country an independent United Kingdom of Libya. His rule ushered in a period of internal political stability and the establishment of good relations, not only with the Arab world but also with the West. Additional steps towards political reform followed, with the first elections for parliament being held in 1952. In order to build bridges of cordial relations with its Arab neighbours, Libya joined the Arab League in 1953.

On the international front, Libya enjoyed very warm relations with Britain and the US. This was exemplified by the special treaties reached with both countries. Britain obtained the right to establish military bases for 20 years and in 1954 the US obtained a similar concession.

Additionally, and to ascertain itself as a new member of the international community, Libya joined the UN in 1955.

The government was also looking into the viability of economic independence. Hence in 1956 two American oil companies were granted rights for oil exploration. Libya, officially for the first time, started oil exploration in 1961 when King Idris opened a pipeline that linked all the important oil fields to the Mediterranean Sea.

Furthermore, additional political steps were taken so as to make political representation inclusive. Amendments were introduced to the constitution in 1963, which unified the country. Women were allowed to participate in elections. By 1964, Libya had negotiated an agreement with both Britain and the US to close the military bases.

3) Revolution

Fall of monarchy: winds of change

Like others, Libya was not immune to the revolutionary wind that was sweeping the region. This time it was marked by a change from a monarchial system of government to one of party and ideology. Sentiments of hostility towards the West, and Arab nationalism, would be its main characteristics.

In 1969, a group of young army officers staged a coup and the Libyan Arab Republic was established. Colonel Muammar Gaddafi became the chairman of the newly established Revolution Command Council.

The constitution was nullified and a temporary one came into effect. In the same year, a confederation comprising Libya, Egypt and Sudan was established. Relations with western countries turned sour. British and American military personnel left Libya in 1970 following an agreement with the new regime. The British airbase in Tobruk was closed along with the American Wheelus air force base in Tripoli.

The principle governing economic activities was also redefined with the government taking economic measures to nationalise the oil industry, introducing state socialism. In addition, control of the party and its ideology on all aspects of life in the country was strengthened. In 1971, the Arab Socialist Union was created as the sole political party in the country.

During the same year, a proposition for the Federation of Arab Republics (FAR) comprising Libya, Egypt and Syria was approved by a national referendum — one that never saw the light of day.

A second attempt at unity was pursued in 1972 as Libya and Egypt talked of a merger — but this also never materialised. By 1973, Gaddafi announced the initiation of a ‘cultural revolution' under which ‘people's' committees' were created across the country — in schools, universities, hospitals, workplaces and administrative districts. This was done to enable the party to spread its tentacles across all aspects of society.

But during this year another development took place. Libya got assertively involved in the affairs of its African neighbours. Northern Chad was occupied by Libyan forces, and later Tripoli got involved in the civil war in 1980.

Further measures to deepen the one-man, one-party rule were adopted.

In 1975, Libya's name was changed to ‘Jamahiriya' — which literally translates into state of the masses. By the end of the year, Libya changed the colour of its flag to green. This was in keeping with Gaddafi's Green Book — composed as a single point of reference for all activities governing the daily life of a nation and its people.

Yet this confined single outlook started creating voices of dissent. During the year, students protested against the system of absolute state control. The protests were brutally suppressed. In the same year, there was a failed coup attempt by officers.

4) Socialist Era

In 1977, Gaddafi incorporated additional changes to reflect the principles of socialism and ‘the people' as he would describe it. Constitutional changes were endorsed by the General People's Congress which recommended the country's name be changed to the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. He declared it a ‘people's revolution'. Massive structural economic changes were undertaken the following year.

This period was also defined by Libya's standoff with the world. In the 1980s it stepped up its connections and involvement with many organisations considered illegal by the West, including the Red Brigades and the Abu Nidal group.

In 1981, two Libyan aircraft were shot down by the US over the Gulf of Sirte and an embargo was imposed on the country. The UK in 1984 broke off diplomatic relations. This came after a British policewoman was shot dead outside the Libyan People's Bureau, or embassy, in London while anti-Gaddafi protesters were demonstrating.

For the West, Gaddafi's actions had reached an intolerable level. He was seen as someone who insisted on breaking all the rules governing international relations. In 1986, Gaddafi survived US bombings of Tripoli and Benghazi, which killed about 100 people including Gaddafi's four-year-old adopted daughter Hana. The retaliation was in response to the bombing of a Berlin disco frequented by US military personnel of which Libya was accused.

Soon after, Libya tried to carry out some internal changes in an attempt to improve its image abroad. In 1987, measures were taken to liberalise the economy from its socialist structure and a number of political prisoners were freed the following year.

But these changes were not enough. International powers still accused Libya of its direct involvement in terrorism. In 1992, the UN imposed sanctions against Libya after it refused to extradite Abdul Baset Al Megrahi and Al Ameen Khalifa Fahimah — both suspected of bombing a Pan Am airliner over the Scottish town of Lockerbie in 1988. But towards the end of the 1990s, Libya began to adopt a more lenient and flexible tone in its relations with the world.

In 1999, the two Libyans were handed over for trial in the Netherlands under Scottish law. Diplomatic relations were then restored and UN sanctions suspended. The special Scottish court issued a verdict in 2001 which found Abdul Baset Al Megrahi guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment. The second suspect, Fahimah, was found not guilty and freed.

And, for the first time in decades, the Libyan leadership was willing to adopt extreme measures that would enable it to survive in a world that had drastically changed since it came to power. It was ready to build bridges and for that any concession was acceptable. It began with the US and Libya holding talks in 2002, a first, to mend the decades-old hostility.

And 2003 would prove to be an eventful year. To close the chapter, Libya agreed to pay $2.7 billion (Dh9.9 billion) in compensation to the families of the Lockerbie bombing victims. It also sent a letter to the UN Security Council confirming its responsibility for the attack.

Libya was then elected chairman of the UN Human Rights Commission, despite opposition from the US and human rights groups.

Later in the year, the UN Security Council voted to lift the sanctions. Libya in return declared it would abandon its programme to develop weapons of mass destruction. Additional deals to remedy other problems were also pursued.

In 2004, a deal was reached to compensate families of victims of a French passenger aircraft which was bombed in 1989 over the Sahara. Libya also agreed to pay $35 million to the victims of the Berlin nightclub bombing.

The relationship between Libya and the West took a 360 degree turn and it was marked by western leaders paying a visit to Gaddafi or receiving him in their respective capitals. The first was British prime minister Tony Blair who visited Libya in 2004 — the first such visit by a British premier since 1943. In the following year, and for the first time since the revolution, Libya opened its oil and gas sector for exploration licences. In addition, the US in 2006 declared the restoration of full diplomatic relations.

Further steps to incorporate Libya were adopted with chairmanship of the one-month rotating presidency of the UN Security Council being given to it in 2008. During the same year, Libya and the US signed an agreement under which all victims of bombing attacks on each other's citizens were to be compensated. In a historic visit, then US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice arrived in Libya, the highest level US visit to the country since 1953.

Yet Libya also had its own demands, especially from its old colonial occupier. Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi apologised for damages inflicted by his country then and signed a $5 billion investment deal as a means of compensation.

There were many things for the regime to celebrate in 2009. For one, it marked Gaddafi's 40 years of rule. In addition, the African Union elected him as its chairman. Furthermore, Al Megrahi was released by the Scottish authorities on compassionate grounds and returned home to a hero's welcome.

Political and economic openness were the defining parameters for Libya. In 2010, a deal was reached with Russia to purchase weapons worth $1.8 billion. In addition, BP announced that it would start drilling off the Libyan coast.

The EU and Libya also signed an agreement to slow illegal migration. But matters in the Arab world took on a new direction when protests erupted in Tunisia. Soon, Libya also faced the same fate and the regime's legitimacy, as well as its very existence, came into question. The beginning of the end would come in full force in 2011 following the arrest of a human rights campaigner in Benghazi. The protests soon spread to other cities.

Timeline