After Savar tragedy, it’s time for international minimum wage

Savar tragedy has created a huge wound in the minds of the people of Bangladesh

For Bangladeshis, the tragedy at the garment factory in Savar is a symbol of the nation’s failure. The crack that caused the collapse of the building has shown that if Bangladeshis do not face up to the cracks in their own systems, as a nation they will be lost in the debris. Today, the souls of those who lost their lives in the Rana Plaza tragedy are watching what the rest of us are doing and listening to what we are saying. The last breath of those souls surrounds us.

Has the nation learnt anything at all from this terrible loss of so many lives? Or will Bangladesh have completed its duty by merely expressing its deep sympathy? What should we do now, even as news of a deadly fire in another factory in Dhaka reaches us?

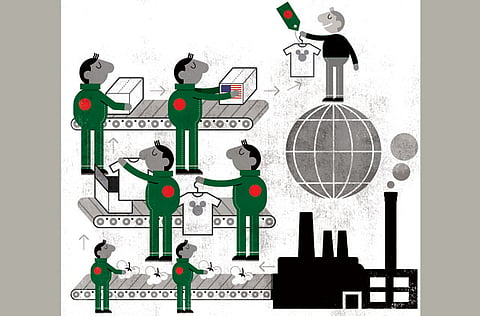

Important questions have been raised about the future of the garment industry. Pope Francis has said buyers are treating the garment workers like slave labourers. A very large foreign buyer, Disney, has decided to pull out of Bangladesh. Others may follow. If that happens, it will severely damage the nation’s social and economic future. This industry has brought about immense change in the society by transforming the lives of women. We cannot allow it to be destroyed. Instead, Bangladeshis must be united as a nation to strengthen the garment industry and foreign companies must play their part too.

I propose that foreign buyers jointly fix a minimum international wage for the industry. This may be around 50 cents an hour, twice the level typically found in Bangladesh. This minimum wage will be an integral part of reforming the industry, which will in turn help prevent future tragedies. We have to make international companies understand that while the workers are physically in Bangladesh, they are contributing to the businesses worldwide: They are stakeholders. Physical separation should not be grounds to ignore the well-being of these labourers.

Of course, we have to be prepared for a negative market reaction. Some will argue that Bangladesh will lose the competitiveness it has gained by offering the cheapest labour. To retain its competitiveness, Bangladesh will have to increase its attractiveness in other ways, for example, by increasing productivity and specialised labour skills, regaining buyers’ trust and ensuring workers’ welfare. However, until the nation is able to fix an international minimum wage, it will not be able to pull its workers from the grievous category of “slave labour” that the pope had placed them in.

Gaining support for a minimum wage will not be easy, but through sincere discussions with politicians, business leaders, citizens, church groups and the media in consumer countries, it can be achieved. In the past, I have tried to convince foreign buyers — but without success. Now, after the Savar tragedy, the issue has gained a new urgency. I want to mobilise my international and Bangladeshi friends to make stronger and more persistent efforts this time. It will not be necessary for all the companies to agree to a minimum wage at the same time. If some leading firms take the initiative, it will start the ball rolling.

There is also another practical way to help ensure better standards for Bangladeshi garment workers. Let us say a garment factory produces and sells a piece of clothing for $5 (Dh18.39), which is then packaged and shipped to New York. This $5 includes not only the production, packaging, shipment, profit and management cost, but also indirectly covers the share that goes to the cotton farmers, yarn mills and the cost of dying and weaving.

When US customers buy this item from a shop for $35, they feel happy that they have got it at a bargain. But everyone involved in the production collectively received $5. Another $30 was added in the US for taking the product to the final consumer. Now, with a little effort, we can make a huge impact in the lives of workers. Will a consumer in a shopping mall be upset if he or she is asked to pay $35.50 instead of $35? My answer is no, they will not even notice that. If we can create a Garment Workers Welfare Trust in Bangladesh, with that additional 50 cents, we can resolve most of the issues the workers face — safety, work environment, pension, health care, housing, children’s health, education, child care, retirement, old age and travel. Everything can be taken care of through this trust.

Bangladesh exports garments worth $18 billion each year. If all the garment buyers accept this proposal, the trust will receive $1.8 billion each year — that is $500 in the trust for each of the 3.6 million workers. All we have to do is to sell the item of clothing for $35.50 instead of $35 — a barely noticeable change to the price can work wonders.

Of course, international buyers may argue that the extra 50 cents will reduce the demand for the product and that their profits will shrink. But an arrangement can be offered to them whereby their sales will actually go up. The extra 50 cents can be a marketing tool to make the product more attractive to consumers. We can put a special tag on each piece of clothing, saying: “From the happy workers of Bangladesh, with pleasure. Workers’ well-being guaranteed.” It can be endorsed by Grameen, the NGO Brac or some other respected international organisation. There can be a beautiful logo to go with it.

When consumers see that a well-known and trusted institution has taken the responsibility to secure both the present and the future of the workers who produced the garment, they will not mind paying that extra 50 cents. Consumers, in fact, will be proud to support the product and the company, rather than feeling guilty about wearing a product made under harsh working conditions.

I do not expect all companies to immediately implement my proposal, but I hope at least a few to come forward to experiment. Governments and organisations that work to protect labour rights, citizens groups, church groups and the media will step forward to support it, too. This issue should attract attention more urgently now in the light of the Savar deaths.

Pulling the industry out of Bangladesh is not a solution. It will be unfortunate for Bangladesh and for the foreign buyers. There is no sense in them leaving a country that has benefited a great deal from their business, a country that can have continuing, rapid and visible economic and social progress because of these companies. I believe these companies will remain in Bangladesh and take pride in creating a new society and economy. Changes are taking place in the world of business. Even if they are tiny changes, they are coming nonetheless. We can accelerate that change.

The Savar tragedy has created a huge wound and deep pain in the minds of the people of Bangladesh. I pray that from this deep pain we will find a way to resolve the problems. When we watched the tragedy unfold on television screens, it made us aware of what Bangladesh’s dysfunctional system has led us to. After all this, will we just keep watching as more such incidents keep happening, again and again?

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Muhammad Yunus is a Bangladeshi banker and professor of economics who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his development of microfinance.