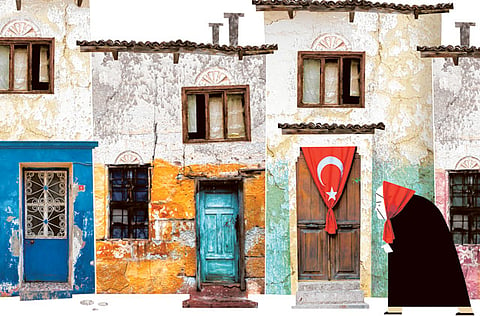

Window on society

A microcosm of Turkey on the eve of the 1980 military coup

Silent House

By Orhan Pamuk,

Faber & Faber,

352 pages, £6.99

Orhan Pamuk has often written of the spirit of hüzün, a peculiarly Turkish brand of melancholy he considers characteristic of Istanbul and its people as they struggle to live with dignity among the ruins of empire.

This sentiment pervades “Silent House” and its lonely characters, adrift in a world where they feel ill at ease. This was the Nobel prizewinner’s second novel, published in Turkish in 1983 but never before translated into English. It is a period piece, offering a foretaste of the author’s better-known work, and a snapshot of his country that many Turks might now view with nostalgia.

The setting is Cennethisar, a faded resort and a place of exile: not Europe, nor even Istanbul. Fatma, a widowed matriarch who has imprisoned herself in the town, recalls her childhood pleasure reading “Robinson Crusoe”, a “confusing book” in which “an Englishman lived for years alone on a desert island because his ship had sunk”. She is joined by her three grandchildren from Istanbul, who spend part of the summer at Fatma’s ramshackle mansion.

Metin, the youngest, dreams of making enough money to study in America and spends his nights pursuing a high-society girl at the rich children’s parties. His sister Nilgun gets up early to perfect her suntan — attracting the attention of Hasan, a local boy who was a childhood playmate but is now associated with a nationalist gang that extorts money from local shopkeepers.

Faruk, the elder brother, takes refuge from divorce in drinks, food, and his historian’s work in the municipal archives where he weaves stories of the past around fragments of Ottoman court records.

Fatma broods in her bedroom (“Then I think about how I’ve lived for ninety years, and I am horrified”). She dwells on her poisoned years of marriage to an over-idealistic doctor, who squandered her wealth and his talent on a futile quest to force-feed his compatriots European secular values. Finally there is Recep, a dwarf, who labours thanklessly for the family and struggles in a society with little tolerance of his disability.

Constructing the narrative from a series of introspective monologues — a trick used to dazzling effect in his later novel “My Name is Red” (1998) — Pamuk gradually reveals the moments of violence on which the family history hinges; violence still latent in its tangled relations.

This domestic drama is a microcosm of Turkey on the eve of the 1980 military coup, when the polarisation of the country between radical left and conservative right, secular and religious, had reached such an extreme that the daily papers carried lists of young people killed in street battles.

Pamuk has captured Turkey at a time when its eldest generation could remember the fading years of the Ottoman Empire; when the modernising, westernising zeal of the Republic’s early years had turned to disillusion, and a sense of national inadequacy led younger people to look abroad, to radical ideologies or to fantasies of the past. Through the confusion of his younger characters, Pamuk reflects on a national sense of confusion over where Turkey — still a young country — was then heading. Hasan, in a moment of optimism, thinks: “There are so many possibilities ... history, our history, the thundering beat of the war drums and the fear in the heart of the infidels who heard them: yes, a person could become someone completely different. We are not slaves.”

“Silent House” is best read in tandem with Pamuk’s most recent novel, “The Museum of Innocence” (2008), in which a Pamuk-like narrator looks back with detachment on the self-destructive love of his youth. Turks today would recognise the strains in society he depicts in both books but the country has grown, in economic promise and in confidence, since Pamuk chronicled the world of “Silent House”.

–Financial Times