Behind the veil, a modern Arab woman

Dubai–based British artist Patricia Millns wonders why those who wear the niqab choose to do so and ventures beyond the stereotypes

Patricia Millns has lived in the Middle East for almost three decades. Her art comes from her deep understanding and love of the culture and the people of the region. The Dubai-based British artist is known for using local textiles and clothing in her work. The colour white, the use of words, repetitive patterns and metal threads are also part of her signature style. All these elements are present in her latest body of work, titled “Emra’a adornment”.

The main focus of the work is the niqab worn by many Arab women. In recent times, the attire of Muslim women, especially the niqab, has become a politically loaded symbol. But Millns looks at it in the context of cultural identity and personal choice and as an adornment. She goes beyond the physical, socio-political, religious and ideological layers of the garment to pay tribute to the woman behind it.

“Emra’a is the Arabic word for ‘woman’, and this show is a celebration of women, especially Arab women. I have been working closely with Arab women since I came to this region and they are strong, intelligent, modern women. Many of them wear the niqab and I see this garment as something that adorns a woman and makes her look more beautiful. I know that in this region, the niqab is a matter of choice and I have always been fascinated to know why the women who wear the niqab choose to do so. Over the years, I have spoken about this to many women and this exhibition was born of those conversations and interactions,” Millns says.

The centrepiece of the show is an installation featuring several rows of niqabs, hanging from the ceiling. But unlike the traditional niqab, which is black, these are all white. Disassociated from the body, floating in the air and devoid of colour, these niqabs are free from all conflicting meanings. But the artist has added many tiny details to offer insights into the minds of the wearers. She has extended the cords used for fastening the niqab around the head, so that they reach down to the floor. And she has embellished the niqabs with traditional decorations such as coins, cowries and beads. But, the beads are made of rolls of paper taken from the latest fashion magazines.

“I made the straps extra long because I wanted to show that these women are flying high in pursuit of their dreams and ambitions, but they have kept their feet on the ground and are rooted in their culture. The beads made from 21st-century fashion magazines indicate that the women who wear this traditional piece of clothing also wear the latest fashions from leading international brands and are certainly not living in the past. The uniformity of clothing unifies and strengthens a group and I wanted to show that by arranging the niqabs to look like a group of women. I want to encourage visitors to walk through the rows and enter this “private space” to explore and understand what it stands for and to reiterate that despite the outward uniformity in this faceless group, it is made up of individuals with distinct personalities,” Millns says.

The installation is complemented by a series of mixed media works on paper that represent a deconstruction of the niqab. Millns has broken down the niqab into three flat pieces of paper representing each panel of the garment. And she has embellished the pure white pieces with paper beads, silver thread and handwritten words. Often, the words are partly hidden by a veil of loose strands of thread. “The words, which include phrases such as ‘I am protected’ and ‘don’t judge me’, reflect what women said to me about the niqab. These women wear it to protect and to cover, not to beautify, but I added the words ‘I am beautiful’ because I feel that they are beautiful,” Millns says.

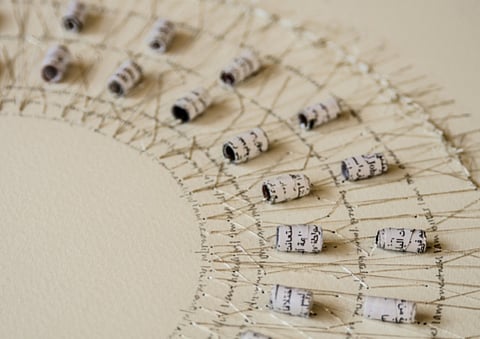

Another set of artworks features repetitive, circular patterns on white paper created with handwritten words, simple stitches, decorative coins and beads made from pages of Arabic magazines. In many pieces the artist has used beautiful, old and rare paper doilies from her collection as a reference to Arabian hospitality and the serving of food. To underline that she sees clothing as an object of adornment, the artist has also created a series of circular necklaces, bracelets and collars from unused tea bags, steel mesh, pearls, paper beads covered with writing and white-coloured found objects. “To me a circle represents a woman because she maintains the cycle of life, keeps the family and community together and preserves traditions,” Millns says.

The artist’s pure white artworks have a meditative, spiritual and feminine feel. They are about objects that are meant to adorn the body. But the identity of the wearers is revealed only through their absence and through domestic arts such as stitching and serving food. By decontextualising these items from the body, and by avoiding colour, Millns invites viewers to free themselves from preconceived notions and biases about them and to look beyond the surface. In a world obsessed with appearance and individuality, she leads viewers to a new perception of adornment, self-expression and affirmation of cultural identity.

“Emra’a adornment” will run at Tashkeel, Nad Al Sheba, until January 18.