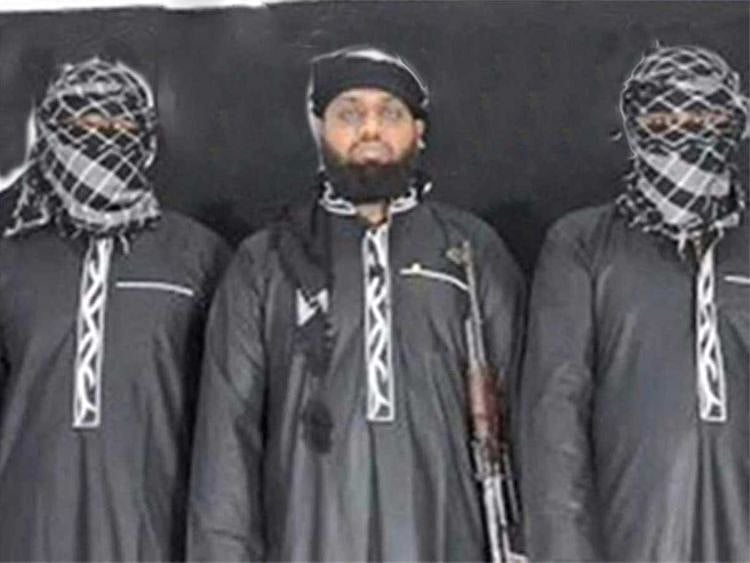

'Black sheep': The mastermind of Sri Lanka's Easter Sunday bombs

The school would hear again of Mohammad Zahran, and the world now knows his name

Kattankudy: Mohammad Hashim Mohammad Zahran was 12 years old when he began his studies at the Jamiathul Falah Arabic College.

He was a nobody, with no claim to scholarship other than ambition.

Zahran and his four brothers and sisters squeezed into a two-room house with their parents in a small seaside town in eastern Sri Lanka; their father was a poor man who sold packets of food on the street and had a reputation for being a petty thief.

"His father didn’t do much," recalled the school’s vice principal, S.M. Aliyar, laughing out loud.

The boy surprised the school with his sharp mind. For three years, Zahran practiced memorising the Quran. Next came his studies in Islamic law.

But the more he learned, the more Zahran argued that his teachers were too liberal in their reading of the holy book.

“He was against our teaching and the way we interpreted the Quran — he wanted his radical Islam,” said Aliyar. “So we kicked him out.”

Aliyar, now 73 with a long white beard, remembers the day Zahran left in 2005. “His father came and asked, ‘Where can he go?’.”

Sri Lankan officials have identified him as the suspected ringleader of a group that carried out a series of Easter Sunday suicide bombings in the country on April 21.

Most of the attackers were well-educated and from wealthy families, with some having been abroad to study, according to Sri Lankan officials.

'Like a spoiled child'

That description does not, however, fit their alleged leader, a man said to be in his early 30s, who authorities say died in the slaughter.

Zahran was different.

Back in 2005, Zahran was looking to make his way in the world. His hometown of Kattankudy is some seven hours’ drive from Colombo on the other side of the island nation, past the countless palm trees, roadside Buddha statues, cashew hawkers and an occasional lumbering elephant in the bush.

It is a town of about 40,000 people, a dot on the eastern coast with no clear future for an impoverished young man who’d just been expelled.

Zahran joined a mosque in 2006, the Dharul Athar, and gained a place on its management committee. But within three years they’d had a falling out.

“He wanted to speak more independently, without taking advice from elders,” said the mosque’s imam, or spiritual leader, M.T.M. Fawaz.

'Like a black sheep who broke free'

Also, the young man was more conservative, Fawaz said, objecting, for instance, to women wearing bangles or earrings.

“The rest of us come together as community leaders but Zahran wanted to speak for himself,” said Fawaz, a man with broad shoulders lounging with a group of friends in a back office of the mosque after evening prayers. “He was a black sheep who broke free.”

Mohammad Yusuf Mohammad Thaufeek, a friend who met Zahran at school and later became an adherent of his, said the problems revolved around Zahran’s habit of misquoting Islamic scriptures.

The mosque’s committee banned him from preaching for three months in 2009.

Zahran stormed off.

Intelligence failings

Sri Lanka’s national leadership has come under heavy criticism for failing to heed warnings from Indian intelligence services — at least three in April alone — that an attack was pending.

But Zahran’s path from provincial troublemaker to alleged terror mastermind was marked by years of missed — or ignored — signals: that the man with a thick beard and paunch was dangerous.

His increasingly militant brand of Islam was allowed to grow inside a marginalised minority community — barely 10 percent of the country’s roughly 20 million people are Muslim — against a backdrop of a dysfunctional developing nation.

The top official at the nation’s defense ministry resigned on Thursday, saying that some institutions under his charge had failed.

Controversy

For much of his adult life, Zahran courted controversy inside the Muslim community itself.

In the internet age, that problem did not stay local. Zahran released online videos calling for jihad and threatening bloodshed.

After the blasts, Daesh claimed credit and posted a video of Zahran, clutching an assault rifle, standing before the group’s black flag and pledging allegiance to its leader.

The precise relationship between Zahran and Daesh is not yet known.

An official with India’s security services, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that during a raid on a suspected Daesh cell by the National Investigation Agency earlier this year, officers found copies of Zahran’s videos.

The operation was in the state of Tamil Nadu, just across a thin strait of ocean from Sri Lanka.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.