Google, Meta’s Red Sea cable delays can slow internet speeds in the UAE

Delays on key global data cables highlight how fragile global internet links can be

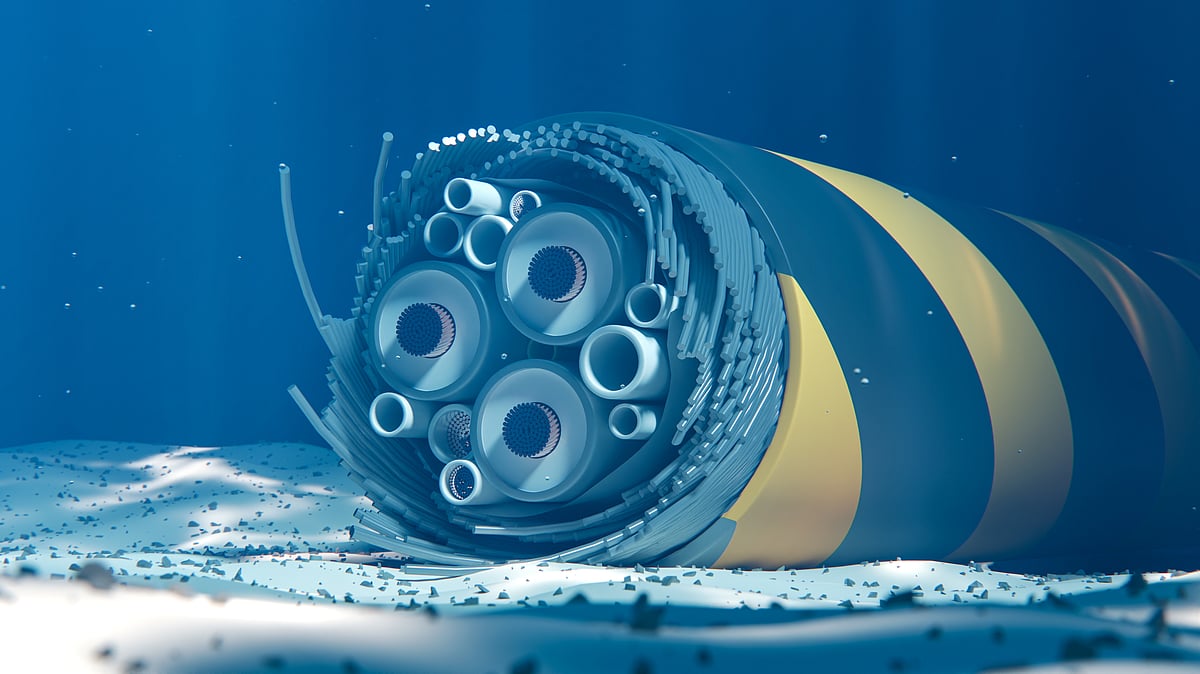

Dubai: Most of the world’s internet moves through thin fibre-optic cables lying on the seabed. When something disrupts those routes, speeds drop — even in highly connected countries like the UAE.

That’s why the latest Bloomberg report on Google and Meta delaying their Red Sea subsea cable projects has raised concerns. The setbacks come after earlier interruptions in the same region left users across the Middle East dealing with slower-than-usual connections.

Here’s what’s happening and why it matters:

Bottleneck at centre of connectivity

Meta’s 2Africa cable and Google’s Blue-Raman system were both designed to pass through the Red Sea — the fastest path between Europe, Asia and Africa. Together, these projects were meant to dramatically increase the region’s bandwidth and improve the long-term resilience of global connectivity.

But the most sensitive part of the route, the southern Red Sea segment, still isn’t complete. Meta confirmed that progress is stalled due to “operational factors, regulatory concerns and geopolitical risk.” Other major cables waiting to pass through the same corridor — including India-Europe-Xpress, Sea-Me-We 6 and Africa-1 — face similar delays.

That leaves one of the world’s most important digital corridors struggling to keep up with demand.

Why Red Sea has become so difficult

The Red Sea has always been the most direct route linking Asia with Europe. Now, it’s also one of the most complicated to operate in.

Security risks have made it harder for specialised cable-laying ships to enter the area.

Negotiating permits with multiple authorities slows down every phase of the work.

Shipping disruptions caused by regional tensions add further delay.

Unlike cargo vessels, cable ships can’t simply reroute around a problem. Their paths are approved years ahead of construction, and changing them is extremely difficult.

How it affects UAE internet speeds

Even with strong domestic infrastructure, the UAE relies heavily on subsea cables to reach global internet hubs. When the Red Sea corridor becomes unstable or incomplete, traffic has to be redirected through longer, slower alternate routes.

That leads to effects users quickly notice:

Slower load times for international websites and apps

Higher latency during video calls and cloud work

Occasional dips in streaming quality or gaming performance

There are also cost implications. Bloomberg notes that cable owners who invested heavily in the new systems cannot generate any revenue until they go live — and in the meantime must pay for extra capacity on other routes just to keep up with demand.

Global tech giants try to fix problem

With the Red Sea now viewed as a “high-risk point of failure,” companies are trying to spread the load across more paths. This includes:

Land-based alternatives through Saudi Arabia and Bahrain

A growing interest in Iraq-based links once considered too risky

Diversifying routes to prevent dependence on a single chokepoint

These alternatives may take time to build, but they point toward a more stable, resilient internet for the region.

Big picture?

The UAE’s digital economy depends on global cables as much as local infrastructure.

When major projects like Google’s and Meta’s Red Sea routes are delayed, the effects can be felt here — even if briefly — in everyday internet performance.

But the long-term shift toward diversified routes is a positive one. Once completed, the new paths will make the regional network stronger, less vulnerable, and better equipped to handle future demand.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.