Fire-proof, 'smarter' lithium-ion battery? How it could change the world

Biggest breakthrough made by Chinese researchers came from changing what’s inside

Lithium-ion batteries quietly power modern life — phones, laptops, e-bikes, cars, even planes.

Thousands of documented fires, some fatal, have been traced back to batteries entering a vicious feedback loop known as thermal runaway, where heat triggers chemical reactions that generate even more heat… and flames.

What’s the big deal with lithium-ion batteries anyway?

Here's what we know so far:

Why do these batteries catch fire?

The culprit is the liquid electrolyte inside the battery. It’s flammable by design, allowing lithium ions to flow. If a battery is punctured, overcharged, overheated or poorly made, the electrolyte can break down, releasing heat and igniting rapidly.

That’s why aviation authorities like the US FAA ban spare lithium batteries from checked luggage — and why airlines are increasingly nervous about power banks in overhead bins.

How serious is the problem in the real world?

Very. The FAA recorded 89 battery incidents involving smoke or fire on aircraft in 2024 alone, with dozens more in early 2025.

One such incident destroyed an Airbus A321 in South Korea, likely sparked by a power bank.

On the ground, e-bike and e-scooter fires are plaguing cities, while a 2024 Aviva survey found over half of UK businesses had experienced lithium-battery-related incidents.

Haven’t scientists tried to fix this already?

Yes — by developing solid-state or gel electrolytes that don’t burn. The catch?

They require entirely new manufacturing processes, making them expensive and slow to roll out.

Great science, tricky reality.

So what’s new this time?

Researchers from The Chinese University of Hong Kong have proposed something refreshingly simple: don’t redesign the factory — just swap the chemistry.

Their breakthrough, published in Nature Energy, involves replacing the standard electrolyte with a temperature-sensitive blend of two solvents that behave differently depending on heat.

How does that actually stop fires?

At normal temperatures, solvent number one keeps the battery tightly structured and high-performing.

If the battery starts heating up, solvent number two kicks in, loosening that structure and slowing down dangerous reactions — effectively hitting the brakes on thermal runaway.

If the approach scales, it could rewrite the rulebook for next-generation batteries — powering everything from smartphones to electric vehicles with fewer compromises and a lot more peace of mind.

Does it work, or is this lab hype?

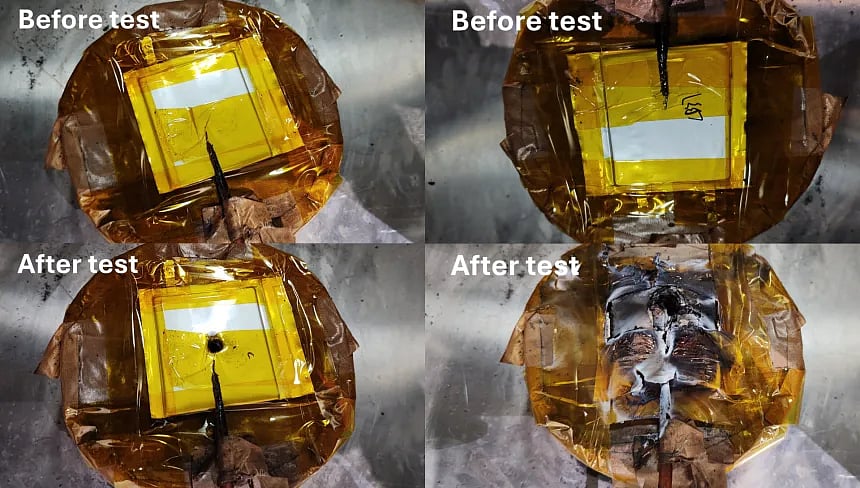

The lab results are eye-opening.

When punctured with a nail, a battery using the new electrolyte warmed by just 3.5°C.

A standard battery? 555°C — enough to melt metal.

Even better, performance wasn’t sacrificed: the battery retained over 80% capacity after 1,000 charge cycles.

Can manufacturers actually use this?

That’s the exciting part. Because the electrolyte is a liquid, it can be dropped straight into existing production lines. No new equipment.

No radical redesign.

According to Professor Yi-Chun Lu, one of the study’s authors, who published their study in the journal Nature Energy in October, costs would be only marginally higher — and likely comparable at scale.

The breakthrough sounds almost like battery wizardry — but it’s grounded in hard science.

“I think the most difficult thing for people to realize about batteries is that when you try to optimise performance, sometimes you compromise safety,” Sun said.

In simple terms, batteries are being pulled in two opposite directions.

Boosting performance means fine-tuning chemical reactions that work best at room temperature.

Making batteries safer, on the other hand, means controlling reactions that kick in at high temperatures — the very conditions linked to overheating and fires.

That tug-of-war has long forced engineers to pick a side.

Until now.

“So we came up with an idea to break this trade-off by designing a temperature-sensitive material, which can provide a good performance at room temperature, but can also offer good stability at high temperatures,” Sun explained to CNN.

When might we see this in real devices?

The team is already talking to battery makers.

If all goes well, commercial products could appear in three to five years.

Scaling up to EV-sized batteries still needs more validation, but experts are optimistic.

What do independent experts think?

In short: impressed.

Researchers from US national labs and leading universities call the work "innovative", "scalable" and "impactful", praising its rare ability to improve safety without sacrificing performance.

Takeaways

This isn’t a flashy new battery — it’s a smarter one.

Under everyday conditions, it delivers strong performance.

When temperatures rise into dangerous territory, it switches gears — sacrificing none of its composure, and far less of its safety.

Think of it as a battery that knows when to chill and when to protect itself.

Sometimes, the biggest breakthroughs come from changing what’s inside, not rebuilding everything around it.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.