We didn't do it. Oh, yes, we did! Been actually doing it for years, but only to help our poor neighbour.

This is the gist of Iran's contradictory response to accusations that it has been lining Afghan President Hamid Karzai's pockets with cash in order to gain a foothold in Afghanistan. The acknowledgement is further proof that the Islamic Republic is pursuing a sneaky line to establish its hegemony in the region and undercut Western influence. There is already much unease in the world about Tehran's role in Iraq, Lebanon and Gaza — and about its secretive nuclear programme.

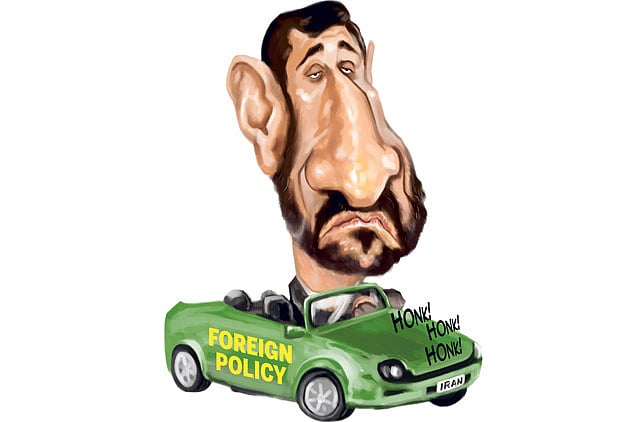

This aggressive foreign policy approach gained pace after the 2005 election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and continues to this day, despite the country's mounting political, social and economic crisis, and in the face of rising international pressure. The question is: why Tehran is willing to take risks at the expense of growing isolation, especially when it could use the money and the energy to address problems at home?

One explanation is that by making a lot of noise the Islamic Republic could divert attention away from the near-disastrous situation at home and create the impression that it calls the tune on the world stage. Ahmadinejad's recent trip to Lebanon, where he was enthusiastically welcomed, was obviously an effort to show off his popularity among the Arab masses and the event has been widely publicised in Iran for domestic consumption. The Iranian leadership desperately needs this image to counter its dismal reputation at home and to disarm the Green opposition, which has called for an end to adventurism and hostile policies towards the outside world. Since the brutal crackdown on angry youth following last year's disputed presidential election, the bulk of educated Iranians (university students, professionals, technocrats and merchants) are alienated from the regime and there is growing discontent among the poor as the government moves to lift subsidies on gasoline and other essential goods. There is also unprecedented dissent from within the ruling circle, with such key figures as former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani pushed to the sidelines. Even the conservative clerics who once formed the backbone of the Islamic regime have retreated into their seminaries in silent protest, but they are known to be angry over Ahmadinejad's "egocentric" manner of governing.

His own man

Since coming to power, the president has pursued a rather independent line from that of the conservative establishment, basking in support from both Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the elite Revolutionary Guards, who back his uncompromising stance on the nuclear issue and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These same extreme positions actually helped bring Ahmadinejad to power and saw him depicted as the right man to realise the radical aims of the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

But, despite his harsh rhetoric, Ahmadinejad is not a classic example of an ideologue and has been rather selective in his attitude towards tradition. He has already challenged some tenets of the revolution in ways his predecessors could have only dreamed of. Even as he pumps the ordinary masses full of false pride and delusions of grandeur, he has boldly reached out to arch-foe the United States, regularly calling for public debate with the country's leaders or offering advice. At home, too, he has taken on his opponents in a manner unprecedented in the Islamic Republic. Last summer he singlehandedly blocked a campaign by other hardliners to re-enforce the Islamic dress code for women; and in yet another bold move, he has tried to revive Iran's pre-Islamic heritage, introducing Cyrus the Great as a new source of pride for the nation. After the Islamic Revolution, the ruling clergy all but denied the country's pagan past and previous presidents did not even dare to allude to this period of Persian history. Just recently, Ahmadinejad and his top aide, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaie, introduced the so-called "School of Iran" as a nationalist source of inspiration for the new generation. The idea has deeply unsettled the conservative clergy, who see it as an attempt to confine the revolutionary ideology within the country's borders.

To date the president remains unscathed and no viable threat to his rule is in sight. But having such a free hand to manoeuvre might turn out to be a curse, as he seems to be growing bolder in indulging his eccentricity. He has trumpeted too many far-fetched ideas but doesn't seem to have a clear vision for the country and the future of the regime in particular. Both Khamenei and the Guards invested heavily in Ahmadinejad in the aftermath of the election last year and they expect him to deliver on his rambunctious slogans. The president now faces hard choices. He either continues with his adventurism or he will have to bury his reputation along with those of his mentors. So it is no surprise that Tehran has chosen to play a cat-and-mouse game with the United States and its allies. This, however, is a risky game which may lead to uncertainty. Iran may be allowed some leeway at a time when the great powers are preoccupied with economic problems and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But the future may hold many surprises. It took years to harden Saddam Hussain's image as an international pariah. It might take even less for Ahmadinejad to meet the same fate.

Mehrdad Balali is a journalist and writer living in California. His novel Houri was recently published in New York.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.