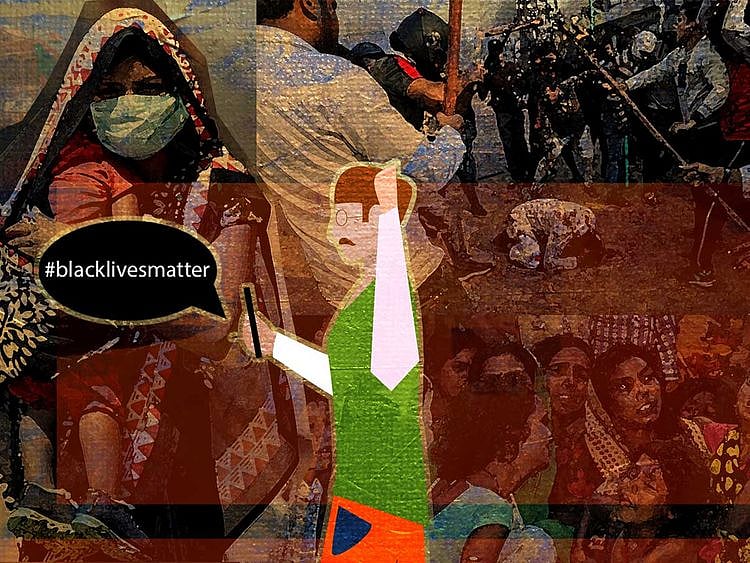

George Floyd protests: And where did India’s collective conscience go?

Indians can learn from the American outrage at the injustice to blacks

Protests, unrest and disorder. That was how the United States reacted to the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed black American, in police custody. Such a scenario is unlikely in India where minority communities continue to suffer at the hands of religious zealots and vigilantes. India never seems to unite the way America does to protest the injustices.

Even after a week, the Minneapolis tragedy continues to reverberate in more than 140 cities across America, bringing more angry people on to the streets. The outrage, the most widespread in decades, is an outpouring of frustration at the socio-economic injustices inflicted on people of colour. All they are saying is black lives matter.

Minorities do not matter. That’s what India seems to say to communities whose plight is similar to black Americans. Racism is the trigger for abuse and other crimes wrought on Dalits, Muslims and other minority communities. Yet the beyond knee-jerk reaction of demonstrations, a sustained movement against religious violence never took root in India.

Why doesn’t India rise in anger to stamp out the scourges of injustice and inequality? Why are religious bigotry and communal violence rife? Has India lost its collective conscience?

Our writers try to answer these questions.

India cannot breathe

By Anupa Kurian-Murshed, Senior Digital Content Planning Editor

8 minutes and 46 seconds. The time a Minneapolis police officer kept his knee on the neck of George Floyd as part of the arrest process. 17 minutes from the time they first arrived at the scene, the 46-year-old black man lay lifeless, apparently from a cardiac arrest, as per the visual investigation team of the New York Times.

March 24, coronavirus-related lockdown announced in India by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And it continues, especially in containment zones. Over 70 days — 40 million internal migrants were trying to get home, across thousands of kilometres on foot, starving, desperate and dying.

17 minutes of the racist brutality stirred the 140 American cities into action, in fact the world, with protests, art and vocalisation — France, New Zealand, UK, India, Lebanon, Chile, Syria ... a graffiti appeared on a part of the former Berlin Wall that read: “I can’t breathe.”

80 Indian migrant labourers died on the special Shramik trains that the government finally set up to transport them back to their villages, after they could no longer deny the mass exodus and the increasing cases of COVID-19 because of this uncontrolled movement.

The Indian Railway Ministry issues a statement, which states: “ … A few unfortunate cases of deaths related to pre-existing medical conditions while travelling has happened.”

They say numbers don’t lie. India’s conscience is dead.

It almost seems pointless to ask why we, as a nation, are showing such apathy to the plight of millions. There is enough coverage across news platforms — print, digital and broadcast. But, it seems to result in a spate of tweets, private citizen attempts to help and nearly deathly silence from most.

Were we always like this? Vociferous with our armchair socialism, but when it comes to standing up for another, the spines suddenly crumble like unbaked clay.

From the old man who died in Rajasthan from exhaustion, while waiting in a queue because of sudden demonetisation by the Indian government, in November, 2016; seven-day abduction, brutal rape and killing of eight-year-old Asifa Bano in Jammu and Kashmir in January, 2018, to drive out the nomadic Muslim community of Bakarwals; to the video of a starving migrant worker eating the carcass of a dog, on the Jaipur-Delhi Highway last month — we seem unmoved.

Is it because Indians have been beaten so much into the ground by decades of injustice, divisive governance, religious hate and lack that our conscience has asphyxiated? It no longer breathes.

Why there is never widespread anger in India

By Omar Shariff, International Editor

The on-camera murder of George Floyd has brought protesters out in more than 140 American cities. What is remarkable — also worrying — is that these mass protests are happening at a time when the world, especially the US, is in the grip of a killer pandemic, and social distancing is a rallying call. Americans of all colour — videos of the sometimes violent protests against police racism show a large number of white protesters — have thronged the streets of the country to make their voices heard against the way police deals with black citizens.

Watching the news, I couldn’t help but juxtapose the Floyd saga with events in my home country, India. The white-black faultlines in America find their match in the Hindu-Muslim fissures in India. While the former is racial (most whites and blacks in America are Christians), the other is religious (most Hindus and Muslims in India are ethnically the same).

While police brutality against black people in the US is well known, with episodic reminders such as the Floyd killing, in India police cruelty against all Indians, but especially Muslims, is such a mundane, routine part of daily life that it barely registers on the radar. People seem to take the wanton, cruel use of the ‘lathi’ — a wooden stick that is the symbol of police humiliation of a citizen in the subcontinent — in their stride. Bollywood movies glorify ‘tough’ cops, approvingly depicting scenes of custodial torture, which is illegal under Indian law.

This lack of righteous anger among the Indian public seems particularly pronounced when the victims are Muslims. Many examples of this came to the fore in the course of the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which culminated in the horrific Delhi riots. Scores of videos of police brutalising Muslim protesters, far from being investigated, drew approving, communal comments on social media. In one particularly nasty incident in February, the police filmed themselves beating and obscenely abusing four badly injured Muslims (one of whom later died), forcing them to sing the national anthem while the lay on the ground, piled one on top of the other.

A video such as that in America would have brought millions on to the streets and would have led to serious trouble for the police department concerned. But the Delhi cops got away with barely anything. Online, the video was met with horror — but also approval in some quarters. Indeed, the fact that the police were bold enough not only to record the incident but also to release it on social media speaks volumes about how confident they were that their actions would have no consequences.

One cannot help but conclude that this confidence stems from the widespread belief that both the state and society do not consider all citizens to be equal.

Indian society has developed herd immunity to injustice

By Alex Abraham, Senior Associate Editor

For the past few weeks, we have seen images of migrants walking hundreds of kilometres back home during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. We have read numerous articles of the hardships they faced on the journey, the tales of courage and the stories of starvation, how children have cycled with their fathers and how parents have carried their infants on their shoulders. Over the past few years, we have also read about incidents of lynching and rape — when they have managed to find their way into the media.

But why is it that a nation of 1.3 billion people finds it difficult to react to such news? Why is it that the country cannot take care of the needs of labourers and workers who have been a significant component of our economy? Is it because we do not have the resources or because we are not resourceful?

As a society, I fear our hearts and minds have become immune to the hardships and difficulties faced by a large section of the people. Years of being exposed to violence and crime have left our hearts calloused. We are not moved anymore by the plight of the beggar sitting by the wayside because we have seen so many of them.

We pontificate about what should be done by sitting in the cosy confines of our homes; we blame the government for not reacting in time to a catastrophe that could have been avoided, we worry about our family and friends in the US because of the riots in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, caused after a white police officer continued to kneel on his neck despite cries that he could not breathe.

But all along, we have continued sitting in our armchairs, pointing an accusative finger at others for not reacting to the wrongs in society.

Scientists have said that one way of beating the new coronavirus is to develop herd immunity — a build-up of immunity in a population due to natural immunity or the administration of vaccines. While we may not have acquired this yet, as a society we have developed ‘social herd immunity’ — a mechanism by which our hearts don’t react anymore to the injustice around us, and our minds become numb to the incidents of violence.

This immunity keeps us from fighting injustice or hate. We fail to react to incidents of rape, murder and lynching because our hearts are not moved to action anymore. Sometimes we go one step further and use statistics to justify our silence. Doesn’t South Africa have more rapes than India? Aren’t there more homicides in the US than in India? The few who have not developed this immunity are the ones listening to their conscience and fighting on — a lonely battle to be heard.

We have become immune.

Has India stopped reacting as a nation?

By Gautam Bhattacharyya, Senior Associate Editor

Yes, ‘n’ how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind

Yes, ‘n’ how many times must …

— Bob Dylan

The memorable lines of Bob Dylan echo in our consciousness as there seems to be no end to the suffering of migrant labourers and their families in India. Their agonising homeward journeys have become a parallel narrative along with the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country.

Staring at the TV news updates along with the rest of the family sometime back, my mother-in-law — close to being an octogenarian — said it was during the Partition last that she remembered as a child such sights of uprooted men, women and children walking for miles. It was a price that the generation may have paid for freedom, but what went wrong on this occasion?

A bit of foresight, maybe, was all it needed to give these millions of out-of-work people a chance to trudge to the safety of their homes. It’s been two months since the reverse migration started and we have gradually got ‘used to’ the sights and sounds. Some of the states that these migrant labourers return will see a spike in cases, and that’s worrying.

The problem with India is, and I say this irrespective of any political dispensation in power, we tend to get ‘used to’ things quite easily. As the country with the second-highest population in the world, we have grown up gauging the extent of any tragedy — be it a natural calamity or a human-made tragedy — with the number of casualties. Deaths have become a number to us, and it’s been no different this time.

It’s almost an organic habit that heinous social crimes like rape or mob lynching — the more recent phenomenon — don’t teach the country enough lessons to shake up its people. As we wear names like Kathua, Unnao or the cases of a Mohammed Akhlaq or Pehlu Khan as badges of shame, a predictable routine plays out every time — knee-jerk screams in the social media, candle marches, perfunctory arrests, storms over coffee cups branded with the TV channels’ logos — and we seem to be back to square one.

Can we, the people of India, ever turn the corner?

‘The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.’

Muslims, migrants and marginalised are India’s black community

By Sadiq Shaban, Opinion Editor

America is alight. Hundreds of thousands have poured out on the streets from New York to LA on the seventh straight day to protest the brutal killing of a black man — George Floyd — at the hands of a white police officer. Often enough in the history of nations, it just takes a spark to ignite the collective conscience of a nation.

By now we all know that Floyd pleaded with the cops to let go off him, echoing those famous words: ‘I can’t breathe’. If the #BlackLivesMatter movement needed oxygen to spring to global consciousness, it was ironically going to be those three words.

Soon enough ordinary people in the world’s oldest democracy responded. Young and old, women and men — braving the pandemic — clashed with cops to register their outrage. Pitched battles took place at Times Square and even outside the White House.

The images coming out of the US in the last few days have jarred strongly with another great democracy — the world’s largest. Coronavirus has undoubtedly disrupted lives in India, but it is the country’s most vulnerable — its poorest and weakest who bore the full brunt of an abrupt lockdown ordered by the Modi government.

The social devastation of the pandemic created a landscape of human apathy in India. And it shows. Images of a migrant worker eating a roadkill near Jaipur — an act of extreme desperation — should have shocked the conscience of the nation but barring a few news reports, there was little fuss. People seemed to get on with their lives. No angry protesters turned up at Jantar Mantar.

Perhaps the shocking spasms of right-wing violence over the last few years have desensitised India — where regular instances of mob lynching and widespread vigilantism have received social approval now.

It still does hurt a smattering of liberals and people of conscience but human life has become so debased in India now that nothing matters anymore — not the rape of a 8-year old nomad girl in Kashmir nor the public lynching of an elderly Muslim on the roadside in the full glare of eager mobile cameras. The orgy is then put on social media for some majority chest-thumping. Somewhere, sometime India’s Muslims, migrants and marginalised became its black community.

The steady drip-drip-drip of bigotry, callousness and indifference can corrode a nation’s soul. Why else would the image of a toddler tugging away at its dead mother on a railway platform not become India’s ‘I can’t breathe’ movement?

An India steeped in self-love

By Sanjib Kumar Das, Senior News Editor

When Sachin Tendulkar releases an autobiography titled A Billion Dreams, I feel proud as one of the stakeholders on a shared plane of collective euphoria. Or for that matter, when Shah Rukh Khan stretches his arms for the umpteenth time on the slopes of somewhere in the Alps or simply says ‘Main Hoon Na’ (I’m there), it’s much more than a mere potboiler … it’s nothing short of living a dream. And with the slightest hint of a border skirmish, my blood boils. ‘Enemy take note: An eye for an eye’, I mutter in zest.

Yet, when the television screen in my living room flashes visuals of those hapless migrants walking home, I merely tell myself: ‘Poor guys, but thank God. I’ve never had to endure this.’ When that child who can barely walk plays peek-a-boo of sorts with her mother on a railway platform, unbeknownst that her mother is no more, I only tell myself: ‘Poor little child, but thank God. I’ve never had to endure even half as terrible as this.’ And when a minor is drugged and gang-raped in confinement for days, I yet again tell myself: ‘What the hell! But thank God, never had to get anywhere close to this.’

Looking at the times we live in, it seems war, Bollywood and cricket constitute the only mass opiates that can make a billion hearts beat for a common cause, a trillion tears roll for a shared sense of grief or ecstasy in a country where our collective consciousness is just a conditioned-reflex to a mojo that’s greased with the ‘here-and-now’ of good living or the mere perception of it.

This is contemporary India: Steeped in self-love to put even a Malvolio to shame!

If you are looking for a common rallying point beyond the precincts of muscular nationalism, robust romance or bravado beyond 22 yards you are most likely to be disappointed. I’ll walk a mile or more to the next Indian Premier League match venue; I’ll be part of a high-octane campaign to match vibes with the men in uniform at the border; I’d definitely like to grab the shampoo brand endorsed by a Khan or a Roshan … but never for once will I delve deeper and ask, ‘Why did that woman with a toddler in tow have to die on a train?’ That image will keep haunting me for sure, but only until the next IPL match hits the headlines or ‘Suryavanshi’ hits the screens. Until such time, let me tweet about George Floyd’s death: Something too trendy to ignore on social media, and too far away to disturb my ‘here-and-now’!

There’s no fire in the belly of India’s middle class

By Shyam A. Krishna, Senior Associate Editor

What happened to us? Did we lose our power to respond to injustice? Recent events in India show that we have become spectators to the communal violence and brutality around us. We seemed to have lost our voice. Our conscience too. Even when protests erupt, they are muted and lose steam in a matter of days.

Sectarian strife, violence against minorities, mob-lynchings, rapes, domestic violence, all continue to wreak havoc on our society. But we choose to look away.

I marvel at the courage of Americans who united in protest against the police action that led to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The anger that raced through more than 140 cities is a reflection of the outrage at social injustices. India could use some of that fire to fight religious intolerance and domestic strife.

The cow vigilantes’ fatal attack on Pehlu Khan in Alwar, Rajasthan, couldn’t ignite anger across the country. Many more targeted attacks on Muslims and other minorities followed. There was no fury on the streets. The Nirbhaya rape in Delhi was the only time in recent memory when there was an outpouring of national outrage. It did help strengthen the laws to fight rape but didn’t stop the sexual assault on eight-year-old Asifa Bano in Kashmir and many others.

We fail to protect our women. We continue to fail our brethren among Muslims and other minority communities. Look at the plight of migrants, whose lives have been torn asunder by the ill-planned lockdowns to combat the coronavirus.

Why do we fail? The answer lies in the rise of the middle class. The middle class in India are the most self-centred people who refused to step out of their comfort zones. Social issues don’t matter. Protests are not for them; they are fearful of offending the government. In fact, they would only be too quick to join government initiatives like the candle-light vigil against COVID-19.

The apathy and antagonism of the middle class are at the core of our inability to rally around a cause. To fight social injustices, people should have empathy. Understand the pain and suffering. Only then will they spring into action. For the middle class, violence against minorities and women are not their problem.

How do we change this? Much of the responsibility lies with the government, which has to lead the charge. Sadly that’s not been the case. Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s condemnations have been too soft and have come too late to make a difference. Unless the leadership shows the will to fight these abhorrent practices, India’s Muslims, women and the poor will continue to suffer.

People should realise their power, and the power of protests to persuade the government to act. Remember that India’s independence was achieved through a mass movement. India needs some of that spirit. But don’t wait for the middle class.

Design: Nathaniel Lacsina, Digital Content Editor and Seyyed Llata, Senior Designer

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.