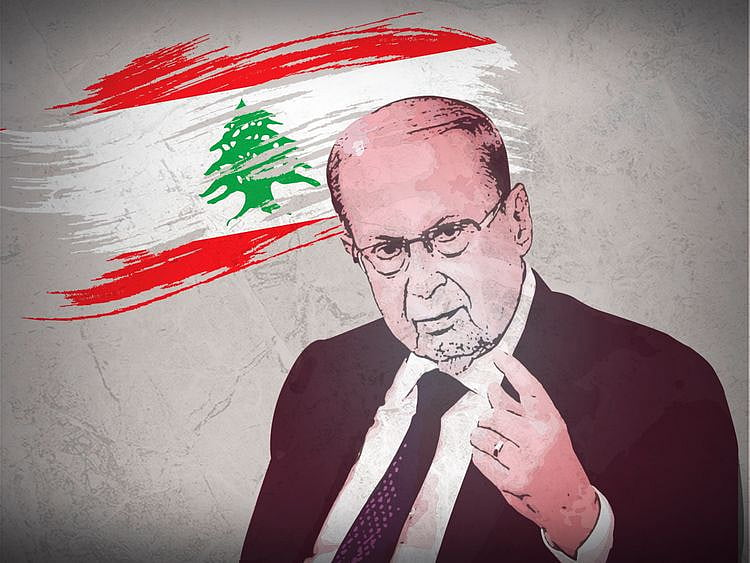

It’s an open secret in Beirut that President Michel Aoun has been toying with the idea of extending his presidential term, when it expires in October 2022. By then, he would be 89. Many believed that this was Plan B for the octogenarian president, whose first choice was to bequeath power to his son-in-law and political heir, Gibran Basil, who also doesn’t hide his desire to become president. Basil’s chances have dropped to comically low levels, however, due to US sanctions, diminishing support within the Christian community, and no backing from Hezbollah. In light of that, President Aoun seems to have switched priorities: Plan A is now to extend his own term, and if that fails, Plan B is to make Basil president.

It is not uncommon for Lebanese presidents to seek a second term, starting with the country’s first president Charles Dabbas, who went for a second term as early as 1929. Others tried, with varying degrees of success, like Beshara Al Khoury, who amended the constitution to allow for himself a second term in 1947, triggering a nationwide uprising against his rule that ended with his resignation in 1952. It was repeated again after the civil war, under both presidents Elias Hrawi and Emille Lahhoud, but none of these presidents were as old as Michel Aoun when they went for re-election.

The idea of extending Aoun’s term was first peddled by MP Maron Aoun, a member of Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement (FPM). He said it in January 2021, insisting, however, that this was his own suggestion and was not mandated by the president. Last week, however, Aoun came out and said it openly: “If Parliament decides that I ought to stay at Baabda Palace, then I will stay.”

The parliamentary obstacle

Aoun forgot to mention what parliament he was referring to. That might be do-able if the current chamber remains in power until October 2022, since his party commands the lion’s share of seats (a total of 29). But even then, that’s still not enough to secure a majority vote, which needs 65 out of 128 MPs. He would still need support from Hezbollah (13 MPs), and a variety of smaller blocs to secure that majority. If his followers are still in power by October, and still command a majority, then they would probably vote for extending his term or for making Basil president.

But this parliament won’t be around in October 2022, given that Prime Minister Najib Mikati has called for early parliamentary elections on March 27, 2022. The chance of the Aounists winning a significant number of seats in any fair elections is slim, to say the least. People are furious with his administration, which among other things, is held responsible for the economic collapse, financial meltdown, and the Beirut port explosion of August 2020. On Election Day, they would either vote for civil society activists who triggered the October Revolution of 2019, or for traditional Christian parties like the Lebanese Forces (LF), the Lebanese Phalange, or the Marada Movement.

For that reason, the Aounists were trying to postpone the elections, claiming that due to security breakdown, it would be unsafe to hold a nationwide vote in March. When that failed, they tried to prevent expatriates from voting, since a large number of them had left Lebanon during the Aoun era and were certainly not going to vote for Aoun and/or his son-in-law.

Aoun seems to have now decided to shelve Basil’s nomination for the presidency, in order to protect him from what seems to be certain defeat in October. Instead, he and his advisers are now pushing for extension of the presidential term, citing Article 69 of the Lebanese Constitution as a legal pretext.

Article 69

That article says that a cabinet has to resign if a prime minister dies while in office, or at the start of a new presidential or parliamentary tenure. This means that Najib Mikati needs to step down by April 2022, although when appointed last September, he was brought to believe that he would stay in power throughout both the parliamentary and presidential elections. Unless a new replacement is immediately appointed, and subsequently approved by the Chamber of Deputies, then Mikati would stay in power in caretaker capacity from April to October 2022.

Cabinet formation is never quick in Lebanon and it often takes months, sometimes crossing the one-year benchmark. Former Prime Minister Hassan Diab resigned from office in August 2020 but was only replaced by Najib Mikati in September 2021, acting as caretaker premier for 13-months. And even if a prime minister is appointed swiftly, it might take him months to form a cabinet. That happened to Tammam Salam, who was tasked with the premiership in April 2013 but did not form his government until February 2014, holding the title of Prime Minister-designate for 10-months.

Neither a caretaker prime minister, nor a prime minister-designate can constitutionally approve of a presidential election, and nor can they attend a presidential inauguration. If Lebanese politicians are unable to decide on a replacement to Najib Mikati, which is very likely, then this mean no presidential elections, no new occupant at Baabda Palace, and a forced extension of Michel Aoun’s term.

Basil’s obstruction methods

What makes this scenario all the more horrifying is that Gibran Basis is well-trained when it comes to obstruction of cabinet formation. That is what he did to ex-Prime Minister Saad Al Hariri between November 2020 and July 2021, putting forth a series of impossible conditions that Hariri could not possibly meet. He asked for the lion’s share of cabinet posts, including all sovereignty posts like defence, foreign affairs, and interior (which has historically been in the hands of a Muslim Sunni).

When Hariri tried meeting him at midway, he raised the bar, insisting on the right to name all Christian ministers in the government, in total disregard to other Christian parties. After eight months of endless bickering, Hariri stepped down. Basil can do just that next spring, making sure that no prime minister is around to supervise the next presidential elections, in order to extend his father-in-law’s term.

Sami Moubayed is a Syrian historian and former Carnegie scholar. He is also author of Under the Black Flag: At the frontier of the New Jihad.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.