Why King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech continues to resonate

Iconic speech on racial equality, unity inspires change, challenges injustice globally

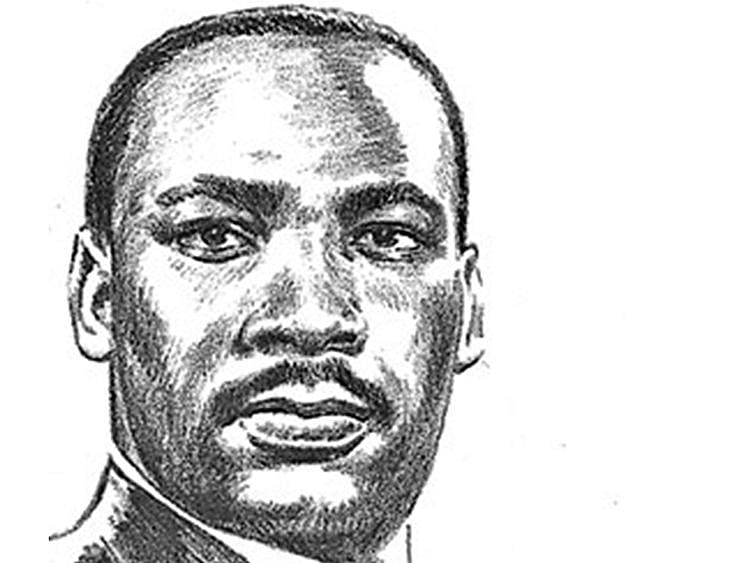

His stature as a major historical figure, one whose adoption of non-violent resistance as the preferred vehicle for a disenfranchised people to achieve social justice earned him the Nobel Peace Prize, is uncontested. Equally uncontested is the fact that he was a spellbinding orator whose “I Have a Dream” speech is universally recognised as not only one of America’s but one of the world’s greatest speeches.

It was exactly 60 years ago, on Aug. 28, 1963, when the Rev. Martin Luther King delivered that speech on the Mall, in downtown Washington, to a crowd of 250,000 people.

In it he envisioned a colour-blind America that lived up to the “dream” of its Founding Fathers — a conscious allusion to the call in a poem by Langston Hughes, the African American social activist, novelist and poet behind the literary form known as “Jazz poetry”, to “let America be the dream that dreamers dreamed” — all the while situating the struggle by Black folks for freedom and equality within the broader landscape of history.

To this day, six decades after the fact, his words continue to resonate with us — both in the United States and elsewhere around the world.

Pre-eminent civil rights leader

In America, he is commemorated each year on Martin Luther King Day (Jan. 15), a federal holiday since 1986, and honoured by a statue in his likeness in the nation’s capital, as well as by the countless highways, boulevards, bridges and parks across the country named after him. Abroad, there’s the Parc-Clichy Martin Luther King in Paris, France; the Martin Luther King School in Accra, Ghana; and the Martin Luther King Church in Debrecen, Hungary; not to mention the well over 1,000 streets in cities throughout the world named after him.

As for his “I Have a Dream” speech, well, it continues to this day, I say, to have a mastering grip on our sensibility, exerting, as it does, a potent hold on people across America, across the world, across generations and across cultures.

Bear with me here as I insinuate myself into this column.

I have listened to and watched online the Rev. King deliver that speech several times over the years and, predictably, was mesmerised by it. But I also often wondered what it would feel like to “see” it — actually see the typewritten script that Martin Luther King held in his hand as he read from it to the 250,000 people gathered on the Mall, most of them Black Americans who arrived there on buses and trains from around the country to listen to what the pre-eminent civil rights leader had to say about their civil rights.

I have a dream

Well, I needed wonder no more last week after I took the subway on a sweltering hot Wednesday afternoon from Cleveland Park, where I live, to the Smithsonian, the stop nearest the 350,000-foot, 10-storey building (five above, five below ground) where the National Museum of African American History and Culture was housed and where the three-page typewritten speech had gone on display beginning two days earlier.

So, here I am. Oh, my! Standing in front of this historic document, which was encased in a glass showcase, reading every sentence in every paragraph, from top to bottom, relishing every word. But wait, where, Oh where, is that section in the speech where King repeats the phrase “I have a dream” over and over again with every paragraph, which rendered it one of the most recognisable refrains in the world, catapulting the speech itself into history.?

I mean, for Heaven’s sake, I mean that part where he says: I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi ... will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice/ I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character/ I have a dream that one day in Alabama ... little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and little white girls as sisters and brothers/ I have a dream/ I have a dream that one day every valley will be exalted ... /I have a dream ...

Well, that part of it was not in the typewritten speech because, I discovered later, King had improvised it. To be sure, I was not surprised. In his speeches, Martin Luther King would often string words together much as a Jazz soloist would string notes together. And like any Jazz soloist while jamming, he improvised a great deal when he spoke publicly.

Contribution of slave descendants

Yet on that day, the improvisation was prompted by the legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson (d. 1972) — considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century — who had earlier that day delivered a stirring rendition of the spiritual “I Been Bucked and I Been Scorned” and who now shouted at him from the speakers’ platform, where she was sitting, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin, tell ‘em about the dream”. (She reportedly was reminding him of a reference he had made in earlier speeches where had riffed on the dream theme.)

King obliged, as he pushed the typewritten text aside and began to improvise, beginning with, “I have a dream ...”

If you, dear reader, unlike me, had known that all along, well, kudos to you. I had not — till that day I was edified by my visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, an august institution that showcases the contribution that the descendants of slaves have made to America.

In the America we know and whose popular culture — though not politics — we admire and whose language we at times communicate our thoughts in, it was these Black folks who reshaped the way music is composed, English is spoken, sport played and cool shown. And without that contribution America today would not just be different but diminished.

I too have a dream. I have a dream that America will one day come to its darn senses and live up to the promises made in its own Declaration of Independence: All men and women are created equal, right? So, what’s holding you?

— Fawaz Turki is a noted academic, journalist and author based in the US. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.