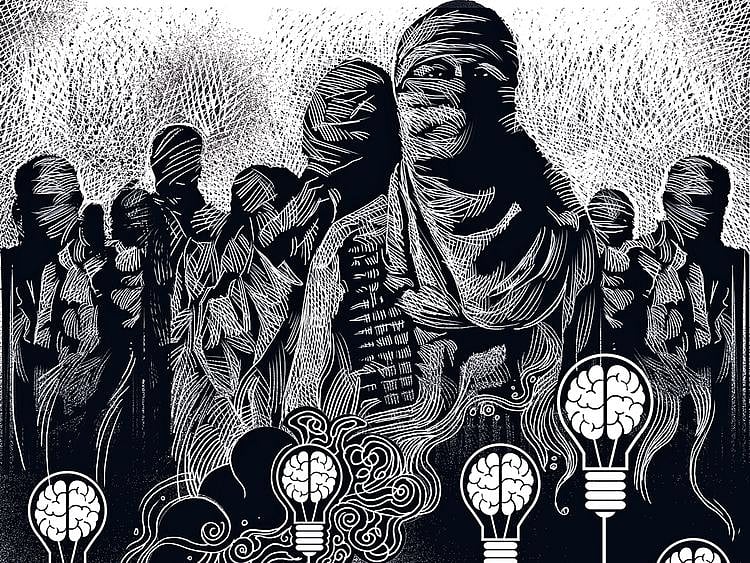

Daesh may have collapsed at the organisational level, with the so-called ‘Caliphate State’, declared in 2014, dismantled with only small pockets of the group remaining in Iraq and Syria. However, a post-Daesh phase would perhaps be a more dangerous terrorist threat, both at regional and international levels. This assessment is not a general prediction, but is based on many indicators that point to a definite danger, and it is essential that concerned parties are well prepared. With the aim of examining the present to provide an outlook for the future, I am sounding the alarm early, and placing my conclusions in the hands of those responsible for issues of extremism, terrorism and security.

The collapse of Daesh raises many important questions — has the ideology behind the organisation died? Where will the thousands of Arab and non-Arab fighters, who believed strongly in the ideology of Daesh and fought for them, go? Does Daesh’s collapse as an organisation mean it is no longer capable of terrorist acts? Will it give in to defeat, or will it seek new forms of action? What would be the new nature of its relationship with Al Qaida? The answers to these, and other key questions, will reveal where we are headed in the post-Daesh period, what our priorities should be and what lessons have been learnt from years of confrontation with the organisation.

Five dangerous scenarios

Several scenarios could arise from the collapse of Daesh; none signal an end to the threat Daesh poses or the death of its ‘idea’.

The first of these scenarios is that Daesh, as a centralised organisation with leadership and structures within a specific land area (Iraq and Syria), becomes a decentralised organisation with various offshoots. This could mean, for example, Daesh in the Arab Maghreb, a sub-Saharan organisation, an organisation in Yemen or Daesh in the Arabian Peninsula, among other incarnations.

This is exactly what happened after the 2001 collapse of Al Qaida in Afghanistan. It crumbled as a central organisation with one specific leadership, but from the remnants it dispersed into sub-organisations in many regions around the world. This included Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, Al Qaida in Mesopotamia and Al Qaida in Sinai, posing a major challenge to the security and stability of these areas.

The second scenario is that elements fighting under the auspices of Daesh will transfer, or return, to Al Qaida. This is particularly relevant in light of indications Al Qaida is rebuilding, and that its founder’s son, Hamza Bin Laden, is preparing to take command of the organisation, directing it to a new phase. Daesh split from Al Qaida because of disagreements over the mechanics of establishing an Islamic caliphate. Al Qaida refused to rush to declare the state, considering it premature, while Daesh believed the state should be declared within a specific land area. However, the collapse of the Daesh project, proven impractical on the ground, could now prompt many of its remaining elements to return to Al Qaida’s ideology, increasing its power base and ability to lead terrorist action, further threatening global security and stability.

The third scenario is that the dissolution of Daesh leads to significant escalation in individual terrorist operations from those who believe in Daesh’s ideology. These ‘lone wolf’ elements, not connected to a centralised organisation, present major security threats regionally and internationally. They are a significant danger as it is likely they have been operating in societies within the region, and beyond, for many years without detection by security apparatus. This gives a large margin for near anonymous movement to carry out terrorist operations, whether on their own volition, or on directives from abroad. Although the individual behind the recent massacre in New Zealand does not belong to Daesh, his actions reveal the inherent danger of ‘lone wolves’ in the terrorism context. He was able to commit a horrendous terrorist act alone, killing around 50 people in a matter of minutes. Security services had no record of him as an extremist or potential threat. This highlights the danger ‘lone wolves’ of Daesh could pose, anywhere in the world, as dormant, undetected cells.

The fourth scenario is that Daesh modifies its methods, whether in Iraq, Syria or elsewhere. It may resort to hiding in caves and mountains, and launching sporadic attacks, as has been the case for Al Qaida and the Taliban in Afghanistan. This is particularly relevant considering reports that the Daesh leader, Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, is still alive.

The fifth scenario is that the Daesh leadership moves to other regions after its collapse in Iraq and Syria. There have been reports that Daesh might resurface in Central Asia or Afghanistan, following the major blows it has suffered. This would mean new starting points in new areas for the organisation.

Returnees from Iraq and Syria

The collapse of Daesh presents another serious problem, one that also emerged after the end of the ‘jihad’ experience in Afghanistan. At that time, many countries in the region, and around the world, faced the danger of ‘returnees from Afghanistan’ — elements that fought against the former Soviet Union in Afghanistan under the banner of ‘jihad’ during the 1980s, with direct support from American intelligence in the form of money and arms. Upon returning to their countries, which included many Arab nations, some engaged in terrorist acts, as they turned against the United States and the West. The predictions are that this scenario will be repeated with the ‘returnees from Syria and Iraq’ — fighters from the countries of the region, and from the West and East, who joined Daesh. Many have already returned home, with many more to follow, and they are thought to number tens of thousands (estimates place the number of foreign fighters who joined Daesh at around 40,000). This poses a significant danger to the security of these countries. The fact that Daesh has collapsed does not erase its ideas and convictions from the minds of its followers; in the countries they have returned to they are time bombs.

Based on these considerations, two realities become clear. First, the ruins of terrorist organisations are breeding grounds for the next terrorist group, like the mythical phoenix from the ashes. Experience attests, in the case of Daesh and others, that as long as the roots and causes of terrorist ideology remain, the collapse of a terrorist organisation is a prelude to the emergence of another, potentially even more extreme and violent. This confirms that security or military confrontation — as important as it may be — is not enough to deal with terrorism.

Inspiring model

Second, ideas — whether good, evil, right or wrong — do not die, they fade and then resurface to take hold in another time or place. The alarming global increase in bigotry and Islamophobia — typified by the horrific terrorist attack on two mosques in New Zealand in March 2019 — provides exactly this environment as it fuels extremism and hatred. ‘Islamist’ terrorist organisations find justification to promote their ideas, spreading a discourse based on the notion that a war against Muslims in the international arena requires counterattack. This keeps the ideology of Daesh, Al Qaida and other extremist and terrorist organisations alive, and helps them attract followers.

Dealing with the post-Daesh phase is no less dangerous, or critical, than tackling the organisation itself. Intellectual confrontation is key to any successful attempt to combat terrorism, because as long as the ideas on which terrorism feeds are not refuted or dismantled, more terrorist organisations will follow, and Daesh will not be the last. This was clearly demonstrated by the events surrounding the war on terror, since 9/11 and thereafter.

The UAE’s approach to countering terrorism is an important and inspiring model. While the UAE places importance on the security and military aspects of the war on terror, taking part in the international coalition against Daesh, it gives even greater importance to confronting terrorism at the level of thought and values.

The UAE leadership believes that its intellectual resources are the most important element in the strategy to confront extremism. As a result, the UAE focuses on promoting values of tolerance, coexistence, dialogue and moderation, along with other ideas that oppose extremism, rejection of others and hatred promoted by terrorist groups. The UAE’s comprehensive approach to terrorism, viewing it as an intellectual problem before a security one, is a model that ought to be adopted worldwide in facing the challenges to come.

Dr Jamal Sanad Al Suwaidi is a UAE author and director-general of the Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies and Research.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.