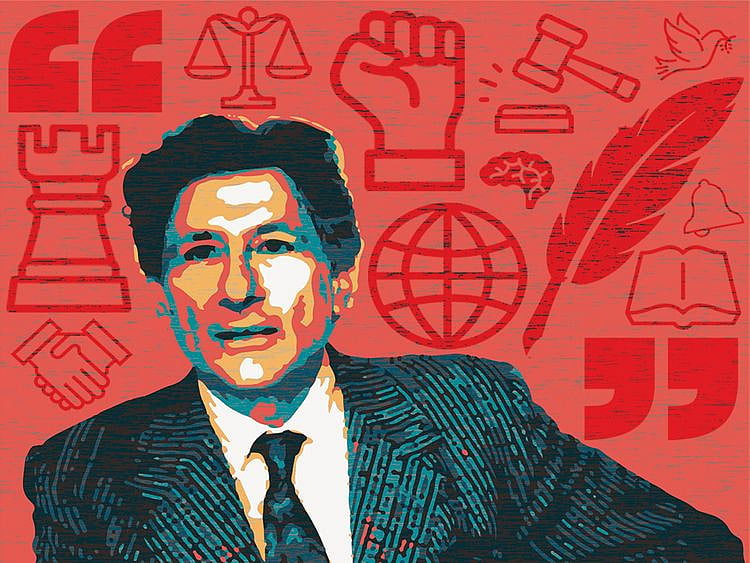

Revisiting the legacy of Edward Said

One of the greatest public intellectuals from Arab world was a rage in America and beyond

On September 24, 2003, after years of sickness with lymphomic leukaemia. Edward Said, a towering figure in the field of postcolonial studies, celebrated both as a cultural critic and a public intellectual, died at 67 years of age in New York City. Tributes poured in from around the world.

Now one of his former Ph.D. students, Timothy Brennan, who in later years became a close friend of Said while the two taught their shared discipline of comparative literature at Columbia University, has published a biography of his mentor called Places of Mind: A life of Edward Said, in which we learn that the respected Palestinian scholar had a secret hitherto hidden from the outside world.

“Over and over again”, writes Brennan, “when I interviewed people who knew him his entire life, they said they knew nothing about this”.

So what was “this”? First, let’s backtrack for a moment.

Challenging the status quo

From the outset of his career, Brennan writes, Said evinced nothing but disdain for poetry and novels as a credible tool “for those who feel the drive to bring about political change”, neither being “the best vehicle to do it”. This dismissive posture by Said bordered on contempt, we are told, as he continued to argue that only the public intellectual is capable of changing the world and challenging the status quo.

No doubt Arabs, a people who have grown up with poetry like they have grown up with their skin, will bristle at the notion that the galvanic force in their poetic tradition never moves them to tears, to action, to conjectures on new meaning in their lives.

No doubt Europeans would equally bristle at the notion that the transformative depth in monumental novels like Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu, Thomas Mann’s The Confessions of Felix Krull and James Joyce’s Ulysses does not, well, transform them as they read every word in them, passing it over their tongues like tasters of rare vintage — novels whose jolting immediacy continues to resound around every corner of their being their entire lives.

Look, true, no one can deny the impact that public intellectuals and cultural critics leave on society. We all concede that these folks have a mastering grip on the marrow of what we call “social change” in our world.

Heavyweight public intellectuals

Consider, as an illustrative case in point, how in the early days of the American Republic, public intellectuals changed the course of American history when, during the 114-day Constitutional Convention in 1787, heavyweight public intellectuals like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison effectively crafted a new nation called the United States of America entirely out of ideas, and then went on to bolster those ideas with 85 newspaper columns, known today as The Federalist Papers, to explain and defend them in detail.

We read everywhere about how public intellectuals proliferated in America in those days, from Ralph Waldo Emerson (d. 1882), who criticised his country’s embrace of slavery, to Harry Ward Beecher (d. 1887), who saved the Union cause by travelling to Europe to deliver impassioned speeches that quelled the Continent’s desire to recognise the Confederacy.

But. A big but. I say there is, in the Western canon, more insight of human, social and political being in, let’s say, Homer, Dante and Shakespeare than the entire oeuvres composed by cultural critics and public intellectuals, who, at the end of the day, live at second hand — writing about Homer, Dante and Shakespeare.

Oh, yes, forgot, the secret.

It now turns out, as we discover in Brennan’s Places of Mind, that Edward Said had a covert affaire de coeur with poetry and novels, which he laboured on, out of sight, in the dead of night, as it were. Said wrote verse and fiction, at both of which he reportedly failed to shine.

Among these unpublished manuscripts, which Brennan had been given access to, were two unfinished novels, at least 20 poems and a short story, the latter rejected by the New Yorker when it was submitted for publication in 1965 — no doubt a chastening experience that could explain Said’s outward expressions of contempt for both genres of writing.

Still, Professor Edward Said (or just Edwa’ar to his close Arab friends in the US at the time, including this columnist) is our man, a cultural critic sans pareil, whose opus, Orientalism (1978) became in the academic world a foundational text in the field of postcolonial studies, and in the wider world a best-seller that enriched cultivated readers’ intellects and altered the focus of their minds.

And what if some belle-letteristes were not divinely imbued at birth with the gift of composing verse and writing fiction! It’s not the end of the world. Or is it?

— Fawaz Turki is a journalist, academic and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.