Musicals: Immigrants’ gift to America and America’s gift to the world

People love the catchy songs, fantastical staging and larger-than-life characters

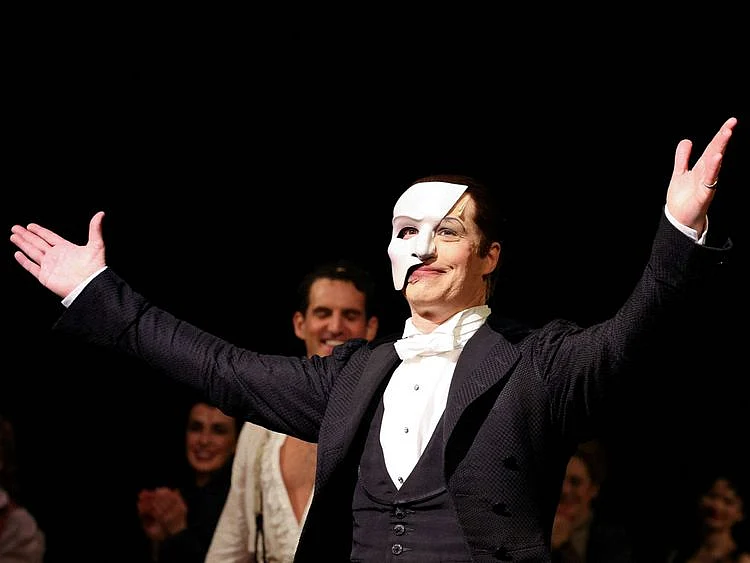

The impeccably crafted musical, whose polished score, Gothic love story and fantastical production have tugged at so many hearts, is no more.

Phantom of the Opera, the venerable blockbuster which became the longest running show in the history of Broadway, bid us farewell two Sundays ago after the cast took their last bow, the thunderous applause died down, the curtain fell and the lights went out at the aptly named Majestic Theatre on West 44th Street in downtown Manhattan.

The show, which opened 35 years ago on January 26, 1988, had had exactly 13,981 performances and played to roughly 20 million people — including usher Sylvia Bailey, who, by her own count, had seen it some 9,000 times over the years, seating patrons and passing out playbills. (That Phantom had grossed a staggering $1.3 billion would be of more concern to those astute investors who had initially put their money in it than to folks like you and me.)

The lure of spectacular Broadway musicals

Americans love their musicals — or more accurately their spectacular Broadway musicals — whose catchy songs, exciting scores, fantastical staging and larger-than-life characters seem to hit a chord in their cultural sensibility, a chord that resonates, one may speculate, with the zestful spirit of the New World, a world that these Americans’ forebears had discovered — although “discovered” here is a term that Native Americans have an issue with.

Still, the theatre musical remains a uniquely American art form, even when you argue that music is a part of our human heritage — for consider how no human community, irrespective of how “primitive” it may be, is absent a musical tradition — that had often accompanied theatrical performances since ancient times.

But musical theatre, as we know it today, that is, as “the Broadway musical”, is indeed a uniquely American art form, and one of recent origin in American history, whose makers and shakers were impoverished, destitute immigrants fresh off the boat, as it were — including immigrants who had been forced to migrate on slave ships.

What we today call “the musical” got its start with the Irish, who began to arrive in the US in huge numbers in the mid-1840s to escape the devastatingly crushing potato famine in their homeland. And it was one of these immigrants, a poet, director and actor called George Cohan, who — according to professor David Armstrong, who teaches a course on the history of Broadway musicals at the University of Washington School of Drama — launched the musical as a distinct genre of theatre in the early 1900s.

Keep in mind that the Irish in those days were seen as “the other”, at the lowest rung among the “impoverished and destitute”, who lived in New York, where, as in other cities on the East Coast, signs were hung outside apartment buildings and workplaces reading “The Irish Need Not Apply”.

So, when George Cohan stood on the stage and sang I’m a Yankee doodle dandy, he not only transformed the ethos and structure of the musical but made a resounding sociopolitical statement about the times.

Around the same time, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and impoverished Black Americans from the Deep South began to arrive in New York — with their own political ideas and musical passions., among them Irvin Berlin, who had, around the same time, emigrated to the US from Russia at age 5 and grew up dancing for pennies in the then predominantly Jewish Lower East Side, and who in later years went on to compose, along with the iconic “God Bless America”, 17 complete scores for Broadway musicals.

And then there was the Black group, The Lafayette Players, who performed, non-stop from 1916 to 1952 — all the while combating long-entrenched racial stereotyping — and in 1921 produced Shuffle Along, a milestone in the development of the musical and a hit that became one of the most popular shows on Broadway.

Modern musicals, all the way from the popular Oklahoma (1942) to the phenomenal Phantom are effectively shows with something to say about our existential condition (pathos, love, despair, anger, hope), musicals based on books married to song and stories put to music, an art farm that truly is immigrants’ gift to America and America’s gift to the world.

And, yes, the world loves these musicals, as Phantom, which has travelled everywhere around it, will attest. The show has played to roughly 140 million people worldwide, where it was performed in 41 countries in 17 different languages in 166 cities, and it is currently running in the Czech Republic, Japan, South Korea, Sweden and London, with new productions scheduled to open in Italy in July and in Spain in October.

What’s Victorian Sponge?

And, Oh, talking about London, a city where the show has become wildly popular. How “wildly” popular? I’ll tell you.

British director Rachel Kavenaugh’s The Great British Bake off Musical, which had its premier at the Noel Coward Theatre in the West End recently, is a show based on the popular television series The Great British Bake Off, in which contestants compete in making British desserts such as Victorian Sponge. (And look, if you’re a Yank and you don’t know what the devil a Victorian Sponge is, well, that’s too bad, mate, I can’t help you because I’m a Yank too.)

Happily, the production of this rip-off of the American musical has only a three-month engagement that ends in the middle of next month. Meanwhile, the horror, the horror!

— Fawaz Turki is a noted academic, journalist and author based in the US. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.