How war classics reveal humanity's dark side

In war, literature emerges as emotional resonance and a powerful conduit for catharsis

Since it found a weekly niche for itself on this page close to two decades ago, this column has annually kicked off the new season with the columnist, an unrepentant bibliophile, sharing with readers his opinion of the best book of the year.

This time around, alas, is different. For the last three months, day-by-day, indeed hour-by-hour, without let-up, we’ve been exposed to the unspeakable imagery emanating from the war waged on Gaza — a baby’s bloody hand, reaching out from the rubble; a child carrying the body of another child, a sibling, on his arms; a mass of people, harried and beaten, marching in search of a safe haven in a strip of land where there is no such haven to be found — imagery destined to lodge in our minds and there acquire permanent residence.

How could one address oneself to the theme of such inhumanity without a persistent feeling of fatuity at one’s use of what by now has become hackneyed lingo like “traumatising”, “heart-wrenching”, “devastating”, “destructive”, “catastrophic” and, the term I used above, “unspeakable”?

War, to resurrect the mother of all clichés, is hell. True. But I tell you, the war in Gaza has already morphed into something else — the heart of darkness, a Conradian allusion to the horrors that “King Leopold’s Ghost” inflicted on the people of the Congo in the late 1880s.

My most favoured books

So, my choice of best book of the year this time around?

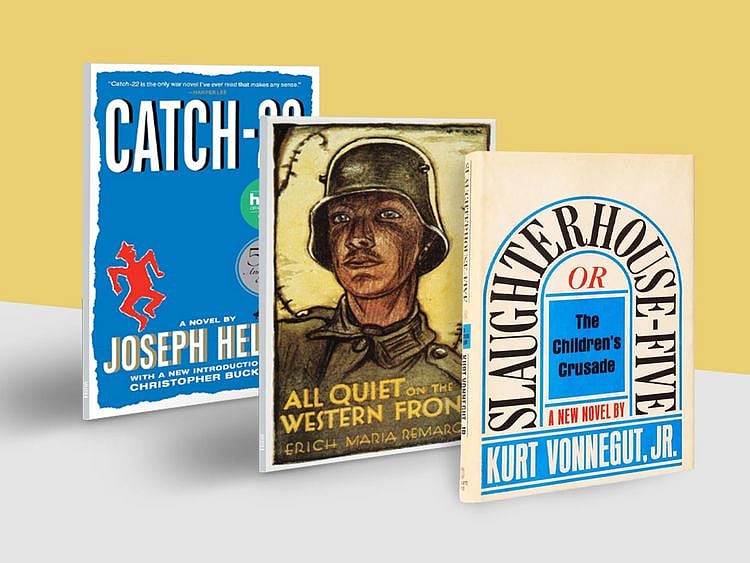

I’m choosing not one but three books. My most favoured books not of last year but of all time — about war.

Men — and it’s almost always men — have been writing books about war since Homer, an oral poet who reportedly was both blind and illiterate (that is, if he ever existed at all) had the Iliad transcribed as he narrated it to his scribes around the 9th Century BC, the Iliad being an epic meditation on the tragic impact of war on the human condition.

But let’s stick to those men who wrote books closer to our time, books that are so well known that I suspect you are at the least familiar with them, if you have not already read them. If so, all the merrier, for we share a mutual attachment to the same literary effusions of our time.

So, in ascending order of preference, I choose All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), by Erich Maria Remarque, which went on to sell 2.5 million copies in 22 languages in its first 18 months in print.

This classic anti-war novel, which recounts in horrific, spellbinding, you-are-there detail the horrors of the First World War, tells the story of a young German soldier who enlists in the Army with 6 of his equally young friends — all imbued with patriotic thoughts about serving the Fatherland.

Within 6 months of bearing witness to those horrors, the protagonist and his six friends become old men, in their minds if not in their bodies. (“I am young. I am twenty years old, yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear ... I see how people are set against one another, foolishly, obediently, innocently slaying one another ... “)

Then, moving right along, closer to our time, we get to Slaughterhouse Five (1969), by Kurt Vonnegut, considered an American classic and one of “the world’s great anti-war books”, a poignant novel whose protagonist, American soldier Billy Pilgrim, is captured by the German Army and held captive in Dresden during the Second World War, when more than 3,900 tons of high explosive bombs and incendiary devices were dropped on the city by Allied forces, killing more than 25,000 people and reducing Dresden to rubble. (“How nice — to feel nothing, and still get credit for being alive”.)

Lose-lose situation

And, finally, I present you with Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961), a war-is-good-for-absolutely-nothing novel so well-known, so popular, so widely read and, well, so mesmerisingly satirical in how it mocks war — actually mocks war to its face — that the title, Catch-22, has passed into common semantic use as a colloquialism that refers to a no-win or lose-lose situation.

The novel follows the exploits of its 28-year-old anti-hero, US Air Force B52 bombardier John Yossarian, who, while trying to maintain his sanity doing his job killing people, is mad as hell that there may be unknown folks out there trying to kill him. (“The enemy is anybody who’s going to get you killed, no matter which side he’s on”, says Yossarian, later adding, “It doesn’t make a damned bit of difference who wins the war to someone who’s dead”.)

Look, every reader’s experience of a work of literature (in this case, fiction, a stylised version of objective reality) is unique, given the fact that we bring our own individual history with us while internalising the work we’re reading — our class background, our cultural archetype, our social consciousness, our religious sensibility, our personal eccentricities and the rest of it. Thus, at times a book that will leave me liberated may leave you cold.

But, let’s face it, we all, in equal measure and in the same way, relate to the notion that few events in human existence have such profound and enduring impact on our collective human consciousness as war does.

Like no other work of fiction, the war novel emotionally transports us to a brutal world we abhor, yet a world whose characters we connect to, whose sad feelings we feel and whose haunted lives we live — and, in an accomplished war novel, live with them.

Oh, the power of literature! Note how when news of war numbs us, war novels make us feel.

— Fawaz Turki is a noted academic, journalist and author based in Washington DC. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.