‘There was a profile of a guy, a “big shot” who visited Mumbai every 2-3 months,’ Chandran reveals. ‘We got reports about him asking for sexual favours. This guy had 3,000 followers online and it turned out a couple of hundred of them had been groomed by him.’

He says many predators pretend that they are from countries like the UK and the US. ‘Children tend to believe they are calling from abroad, not realising it is very easy to get these numbers.’

The revelations by a cyber specialist in this excerpt from my recently released book ‘Stoned, Shamed, Depressed’ that chronicles the secret lives of urban teens was just the tip of the iceberg.

‘Even in a global public chat there is a lot of abusive language, sexual language,’ says a teenager who games frequently.

‘They start by asking girls to show frontal nudes and then shift the conversations to either WhatsApp or Instagram. In Fortnite, older players are abusive towards younger kids, some even as young as seven.’

New age gaming

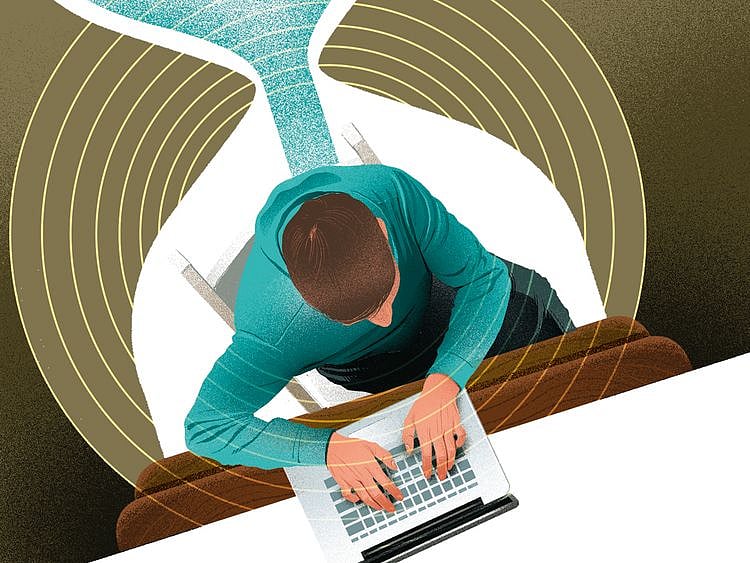

Welcome to the world of new age gaming, where what you see on the surface or a console doesn’t even scratch its underbelly.

Before last year’s PUBG ban in India an estimated 22 lakh people- both children and adults actively played the game. The numbers have only risen in the last year- reports say the gaming industry in the country grew 21% during Covid-19, and the country is mirroring a global trend.

During the lockdown, lonely and isolated at home, social interactions went online, and experts say the exposure to gaming has not just spiked but cases of addiction have also gone up. And, with it, new fears that gaming is establishing itself as the playground of those who are playing with different stakes.

Sexual offenders are targeting young gamers through pop-up chats by gaining their trust online- a phenomenon called grooming- eventually they make their interactions personal on WhatsApp.

The predators offer the unsuspecting children free help to move up a game level or simply gain confidence by sympathising with a player who performs badly.

Cyber experts warn that in multiplayer games a large percentage of players are not who they say they are. A mother walked into her 7- year- old children giggling as they watched a shirtless stranger video- chat.

The man had befriended the children through a voice pop-up chat while they were gaming online, the motive is always to record imagery or videos that can be used later to blackmail the children or their parents.

Fortunately, the mother found out before the children could undress. Families casually dismissing grooming as something to do with clothes have no idea how close to the truth they are.

Unsuspecting children in the thrall of a Fortnite, Roblox or more- doctors liken the dopamine release during gaming to a sugar rush- also sometimes inadvertently leave their chat mics open, leaking family information that no one needs to know.

Cyber specialists warn that although grooming is a recent trend, many children are accessing games that may have malware, leading to their phones being compromised. A lot of it could also be clickbait they warn, saying phones are spammed to install spying apps.

Once the device is infected the person at the other end can stream videos from the front or the rear camera of the child’s device. The trail is not easy, many times it has led investigators to China or Chinese companies based out of Hong Kong.

Sextortion rackets

Gaming is no longer just pop culture, even if cyber safety and privacy are dismissed as collateral damage in the heat of a social media moment.

On the contrary, privacy requires a hawk eye in the times of a pandemic when jobs are lost, minds are wavering, and many are looking to make a quick buck.

In a recent sextortion racket the victims were befriended through social media, porn clips were Photoshopped into their videos and soon they were being blackmailed.

The modus operandi was the same, build trust and then take the chats to WhatsApp. Sometimes, the blackmailers even pretend to be police officers.

When adults are susceptible today, where does it leave children energetically dabbling in a space without proper checks and balances? There is only one note to self: restrict and monitor.

Gaming companies have by and large looked the other way, notice how many 7- year- olds are playing Fortnite even when the legal age is 12.

In 2018, WHO labelled gaming a mental health disorder, but its apprehensions were focused primarily on health as well as social and behavioural concerns.

Those issues especially among the young adults are real. They have spoken of numbness in their fingers, addiction to junk and Red Bull as well as withdrawal symptoms from violent games like Call of Duty manifesting in increased aggression.

A student attacked his own mother because she refused to charge his smartphone- all the parent wanted was for her son to take a break from gaming, a girl in class 8 self-harmed after losing in PlayStation, an 18-year-old killed himself because his parents refused a phone for 37,000 rupees that he desperately wanted for gaming. There are many more stories- of violence against others and self.

Serious levels of aggression

A child psychologist warns that with such serious levels of aggression among the new generation, it may not be too long before they ape the west and its prevalent gun culture.

Perhaps that is alarmist, but the bullet may already be fired. Another counsellor narrated the story of a class 11 student who went looking for a country made pistol to shoot his principal.

A New York Times op-ed questioned whether this violence is a result of the type of games being played or the culture itself. It may not be so black and white for our children.

By 2022, India is expected to have 859 million smartphone users, and this ubiquitous device acts as the conduit for gaming, porn and social media, blurring the lines between urban and rural.

Every week around ten children between the ages of 15-19 make their way to a gadget detox clinic in the South Indian city of Bengaluru. During the pandemic, things have only got worse.

A conversation from last year is still fresh in my mind. For a father who had recently lost his teenage son, Haroon Qureshi was brave, coherent and looking to save others.

One minute his 16- year-old son was energetically playing PUBG shouting instructions to fellow gamers, the next he was on the ground holding his head. The boy was dead before he reached the hospital. The doctors said it was a cardiac arrest.

Qureshi’s son played long hours, the day he passed away he had been gaming for six hours. Many children are hooked for even longer, sometimes tempting fate, at other times strangers on the prowl.

“PUBG finished my child’s life,” says the bereaved father. He hopes someone is listening.

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.