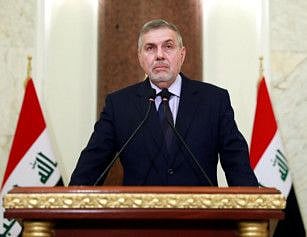

When chosen to form a cabinet earlier this month, Mohammad Tawfiq Allawi was hailed by many as “different” from his three predecessors, given that he had never lived in Iran or been on Iranian payroll. Others doubted his independence, given that he is a former member of the Iran-backed Al Dawa, an all-Shiite party that received Iranian funds during its years in the underground under Saddam Hussain. Those who know him say that he was tremendously influenced by Mohammad Baker Al Sadr, one of Al Dawa’s chief ideologues, who was executed by Saddam back in April 1980. He was also close to the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), another Iran-funded organisation that paid and trained young Iraqis to fight against their own national army during the Iran-Iraq War. Twice in his short-lived political career, Allawi was cabinet minister under Nouri Al Maliki, a self-proclaimed affiliate of the mullahs of Tehran. Allawi’s supporters snapped back saying he had resigned from the Al Maliki cabinet eight years ago, objecting to the sectarian policies of the former premier. Allawi had changed, they insisted, undergoing a personal transformation from a political Islamist to a moderate statesman with a non-sectarian agenda. He was now speaking for all Iraqis and not just for the Shiite community, making perfect for the job of premier.

Allawi’s many challenges

Allawi has promised to choose ministers based on personal merit rather than sectarian political affiliation. That is easier said than done, given that all parliamentary blocs are currently in a tug-of-war, demanding their share of cabinet seats. The Sadrists are asking for the portfolios of interior, finance, and oil. Finance, however, is also being eyed both by the Kurds, who want it to remain in the hands of outgoing minister Fouad Hussain. The Sunnis also want the job, in addition to the ministry of defence. The two major Shiite blocs, Sairoun and Al Fateh, have threatened to back out on Allawi if he doesn’t call for the immediate withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, in light of the January assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani.

Until returning to Iraq from a prolonged exile in the United Kingdom back in 2003, few in Iraq had ever heard of Allawi. He only made it to parliament in 2005 after teaming up with his cousin, ex-prime minister Eyad Allawi, and due to the support of Moqtada Al Sadr, to whom he was related by marriage. And even then, he was a political lightweight. By virtue of his independence, Allawi is a weak man — weaker than any prime minister since 2003. He has no parliamentary bloc behind him and no political party. He hails from none of the hereditary political families in Iraq and has no wealth at his disposal, enabling to buy off loyalty. Even if Iran wanted to bankroll him today, it cannot do that, having stretched itself thing in the ongoing Syria War while suffering from renewed US sanctions since November 2018.

The prime minister-designate is clearly biting off more than he can chew, promising to combat sectarianism, end militancy in Iraqi society, eradicate corruption, and bring wrongdoers to justice responsible for the killing of half a million demonstrators since last October. He has also promised to release those detained for protesting — against the will of the security establishment — and to compensate the families of those killed, while working with the United Nations to implement justice in Iraq. As if that is already not too difficult to implement, Allawi also has to win support of parliament for his new cabinet. Each name will be voted upon independently, making the task extremely complicated. According to the Iraqi Constitution, there is no such thing as an “interim” prime minister in Iraq, as many label Allawi. This will be a full-fledged government, chosen to complete the term of his predecessor Adel Abdul Mehdi, which should end in 2022. That would change, however, if Allawi gathers the courage to call for new parliamentary elections — something that all parties will refuse — especially those with the lion’s share in the current parliament, like Sairoun and Al Fateh.

Learning from his predecessors

Former Iraqi prime minister Haidar Abadi fell from grace, however, when he said he would abide by renewed American sanctions on Iran, instructing Iraqi banks to stop doing business with Tehran. Without even blinking, the Iranians withdrew their support, leading to his political downfall. His successor Adel Abdul Mahdi barely lasted for one year in office, smeared by a whopping death toll on the streets of Iraq. Those demonstrations — which started in Basra two years ago — have not ended. Their backbone is Shiite young men and women who are furious with lack of basic government services, rising unemployment, and autocracy of the ruling elite. Meaning, one former premier was destroyed because he crossed Iran, while the other fell because he came across as too pro-Iranian. This leaves Allawi with the difficult task of standing at midway, hoping to accommodate all of Iran’s concerns while still managing to come across as a political independent. That takes cunning and political acumen, both of which Allawi lacks.

Alternatively, he can jump ship — abandoning both Iran and the United States. That takes courage, however, which he also lacks, putting Allawi in a very difficult task, in which he will likely fail.

— Sami Moubayed is a Syrian historian and former Carnegie scholar. He is also author of Under the Black Flag: At the frontier of the New Jihad.

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.