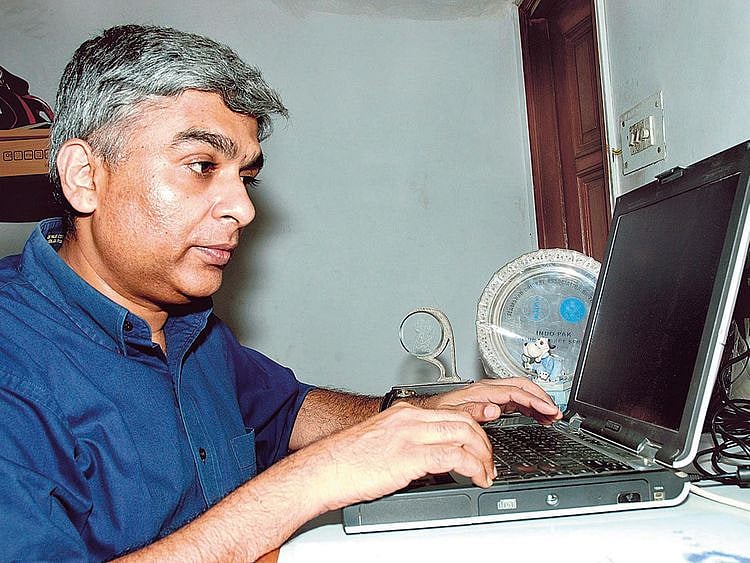

Here’s how George Abraham is helping the visually impaired

How the chairman of World Blind Cricket Council is helping the visually impaired

George Abraham, strides to the centre of the podium, in a hall full of high schoolers in Sharjah. With a crop of thick snowy white hair, a benevolent smile and an easy demeanour, he is instantly likeable. Only a closer glance reveals that he is visually impaired.

To his young audience, George tells, ‘Every problem has a solution, if you are patient and willing to solve it. My attitude is my strength.’

As the keynote speaker at Our Own English High School Sharjah’s annual prize ceremony, George, shared several such life lessons that have truly steered the course of his own journey, from the time when he lost his eyesight from meningitis as a 10-month-old. Today, as a motivational speaker and disability rights activist, he travels the world inspiring others while changing mindsets towards visually-challenged people.

The CEO of Score Foundation, New Delhi, George works for the rehabilitation of the visually impaired and was in the UAE specially for the school’s event at the behest of principal Srivalsan Murugan. The 64-year-old is also the founding chairman of the World Blind Cricket Council and was instrumental in organising the First Blind World Cricket Cup in 1998.

Recipient of several awards, author of a book on inclusive education, podcast host, a member of his church choir and a marathon runner, he is evidently a multihyphenate.

So, what makes you tick, I ask?

‘I love life - from meeting new people, to relishing good food, to singing old classics, I’m passionate about all fine things in life. I have always believed, your challenges need not impede your aspirations,’ George instantly replies.

This personal philosophy is reflected in his talks as well as through the work of his NGO, that has been raising the voice of the blind. His Project Eyeway, established in 2003, as a national helpdesk for the blind, continues to be a one stop resource for people living with blindness, disseminating knowledge, counselling and connecting the visually impaired.

Besides their helpline, Eyeway conducts human resource training, sends job alerts and advocates inclusivity. The initiative has helped a cross section of visually challenged people in India.

George cites the case of a blind MBA aspirant, who at first was denied admission and then went on to successfully complete his course and secure a job in a well-known corporate firm. ‘Interestingly, soon after, the corporate organisation approached us to help them make their work space inclusive for blind employees,’ reveals George.

In yet another instance, thanks to the intervention of Eyeway, a nine-year-old blind boy who had never been to school, went on to show remarkable transformation. In just a few months of being enrolled in a blind school, George narrates, the boy was able to work on a computer, use a mobile, start his studies and interact socially with his peers, taking his family by surprise.

These heart-warming stories give hope to humanity but they might never have happened had George and his wife not visited a blind school in north India two decades ago. ‘We had visited the school as my wife wanted to learn Braille, but the condition of the school shocked us. The facilities were awful, the premises were stinking and the teachers lacked commitment. Their appalling and dismissive attitude towards blind students pained and angered me,’ recalls George.

This incident proved to be a turning point in his life. While he came back feeling grateful of his own supportive upbringing, he also resolved to bring hope to other visually impaired. The following years saw the birth of Score Foundation in 2002 and later project Eyeway.

Yet another game changer in his life was a cricket match that he witnessed in a blind school in Dehradun in the late eighties. ‘The blind students were playing cricket with a ball that rattled (so the players could figure out where it was) and, in that moment, it struck me how powerful the playing arena is. It is so much about one’s mindset, physique, teamwork, leadership and discipline - traits that people don’t usually associate with the blind. I felt this was a great opportunity to break stereotypes and bring more positivity into the lives of blind people. I decided to organize a tournament at the national and international level.’

It helped that George himself was an ardent cricket buff. He dreamt of becoming a fast bowler for India one day. To make blind cricket a professional sport George wrote to over a hundred blind schools in India. ‘Around 45 institutions responded and 24 confirmed participation. Cricket icons Sunil Gavaskar and Kapil Dev agreed to let us use their names as patrons for the tournament,’ he tells.

In December 1990, the first national blind cricket tournament was held in India.

A few years later, in 1996, George became the founding chairman of the World Blind Cricket Council and successfully organised the first World Cup in Delhi in 1998.

Reminiscing about those times George recalls that it was not really smooth sailing. A month before the world cup, a significant share of government funds was cancelled. ‘We were in a tight spot. There were so many murmurs to call off the tournament, but I persevered and as luck would have it, money started pouring in from other sources and we went ahead with the tournament.’

Delving deeper into George’s early life reveals that battling the odds and having that never-say-die attitude for him was a familial instinct. From childhood, his parents never saw his disability as a handicap. He was enrolled in a regular school and was always encouraged to go the extra mile. ‘My parents never took kindly to excuses. They never believed that I had any limitations. If I was a good singer, I was expected to sing in front of an audience or if I was a fast runner, then they pushed me to take part at the state level,’ he shares.

Surprisingly, George who is a graduate in mathematics from St Stephen’s College Delhi University, never studied in a blind school or learnt Braille. ‘There was never a conversation at home of enrolling me in a blind school. This was a great experience for me as I learned to make the best of my ability to lead a normal life rather than a life pitying my condition, adapting around my limitations,’ he says.

His education through four mainstream schools in India was also an incredible community effort involving his parents, classmates, teachers and friends. ‘I could not read my text books or see what was written on the blackboard so my teachers would read everything aloud, and my classmates and parents would help me with my notes,’ he explains.

In an age devoid of current technological aids, George’s inclusive school made his environment as accessible as possible. He recalls, in grade 9 he was keen on studying mathematics, but was told that it was impossible for a blind student as the subject was largely taught on the blackboard. ‘The principal was so compassionate that he wrote to the School Board and let me choose mathematics along with a combination of subjects that I liked. The teachers and classmates again helped me to study my favourite subject,’ he adds.

As a mathematics student, George also learnt along the way that, like all the problems in his text books had a solution, so did life’s challenges. He admits that people with visual impairment don’t have it easy. While the world over the visually impaired are increasingly exploring new venues, they continue to face discrimination in several aspects of life. Thanks to some technological interfaces that do not support options for blind people sometimes operating their own bank account is also a challenge for the blind.

In 2020, George filed a public interest litigation at the Delhi High Court to make banking facilities, especially technological services more accessible to the visually impaired.

Even a 2022 study on workplace technology by the American Foundation for the Blind pointed out that employees with sight loss continue to be hampered in carrying out the basic essentials of their jobs by their employer’s lack of knowledge and commitment to digital accessibility. The participants reported challenges with mainstream technology particularly video conferencing, instant messaging and non-formatted documents prepared by their sighted colleagues.

On his part through his podcast George has been exploring ways to help his community of visually impaired to navigate life by bringing voices of people living with their disabilities. An eternal optimist, the focus for him, is constantly on finding a way out. ‘I always say ‘get out of your comfort zone and never give up because we are as good as everyone else’,’ he says.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.