M Mukundan: ‘All pandemics were followed by great literary works’

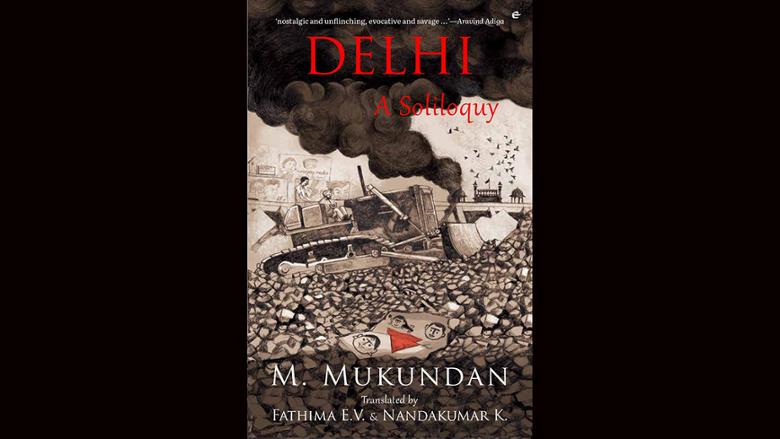

On the heels of the launch of Delhi: a Soliloquy, the English translation of his popular Malayalam novel Delhi Gadhakal, the celebrated novelist M Mukundan tells Anand Raj OK why he prefers not to react immediately to events, how a major pandemic novel could be in the works and why he calls Covid-19 a socialist virus

It’s the late ‘50s and Sahadevan, barely in his twenties is on a train from Kerala headed to Delhi. "It’s in Delhi that your life will begin," he tells himself.

In many ways, it would.

"As soon as you reach Delhi, you should go to meet [India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal] Nehru," Sahadevan’s mother tells him.

Sahadevan does meet Nehru. If only from afar. Once. But he does interact closely with a host of other characters – a campaigning journalist Kunhikrishnan and his wife Lalitha; an artist named Vasu; a call girl, Rosily, who is a romantic at heart; a vocal activist Janakikutty…

During the three-decade-long sojourn in India’s capital, Sahadevan, the protagonist of M Mukundan’s Delhi: A Soliloquy comes to observe the city evolve, often turbulently, from the early decades of post-independence through the wars India fought, to the days of the Emergency until after the riots of the ‘80s.

Originally published in 2011 in Malayalam as Delhi Gadhakal, it was translated into English by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K as Delhi: A Soliloquy, and published earlier this year by Eka, an imprint of Westland.

In many ways, Sahadevan’s life mirrors that of his creator Maniyambath Mukundan, better known as M Mukundan, one of the most celebrated novelists from Kerala.

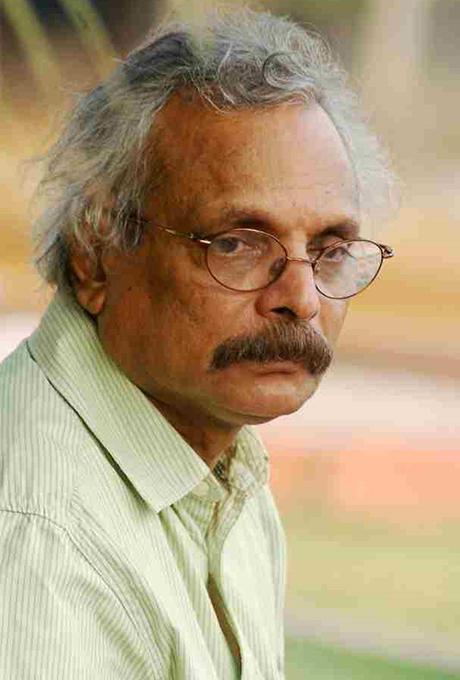

Boarding a train in the early 60s from his hometown Mahe, a sliver of a Union Territory sandwiched by two districts of Kerala, Mukundan arrives in Delhi to work as a cultural attache in the French Embassy. The city would end up being his home for more than four decades inspiring him to write almost all of his 19 novels, not to mention 13 collections of short stories including one in French. Along the way he would pick up a clutch of honours – the Central and State Sahitya Akademi Awards, the Crossword Book Award and the French government’s Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, among several others.

"I can’t lay my finger on it but there’s something in Delhi’s air that inspires one to write," he says with a chuckle, in a telephone interview from his home in Mahe where he is spending his retirement days with wife Sreeja. (His two daughters are settled in the US.)

Feeling the pulse of the people

Consumed by wanderlust and with a passion for perambulating, Mukundan, during his time in Delhi and when not busy at work, enjoyed exploring the capital’s warren of alleys and back roads. Spending hours chatting with the local people and seeing up close how a bustling, thriving population lived, he quickly had a finger on the pulse of the people in the city’s lesser-written-about areas.

Delhi of those days was much like a large village; at best a small town, he says. "It was safe and secure. I once saw Nehru alighting from a car near Connaught Place sans security escort and entering an emporium," he recalls.

Today though the capital has "become one of the most violent cities, although, even at the time, a distinct anti-minority attitude was clearly evident in [some pockets] of the city," he bemoans.

It was during his time in Delhi that some of the most tumultuous events in modern Indian history occurred – wars with China, the clampdown during emergency, the assassination of prime minister Indira Gandhi, the riots that followed in its aftermath… "I was witness to some truly horrifying events," recalls the author. "It was totally surrealistic, someone, perhaps a Gabriel Garcia Marquez, would’ve been able to write about those times in his surrealistic style."

Mukundan, though, could not get himself to write about the events at the time. "A book on Delhi had always been on my mind," he admits. "But I kept delaying it; I don’t usually react immediately to events. I need to internalise them before putting them down on paper."

Then one day, in 2009, he felt he was ready to write about Delhi. "In a sense, the novel is my autobiography but written as a biography of Delhi."

There were several reasons he wanted to write this book: "I wanted to chronicle the events I’d lived through but also tell the story of the Malayali diaspora who lived there."

Another reason was to shine a spotlight on a Delhi that not many people in Kerala had seen. "For many, Delhi brings to mind colourful, cheerful images of Republic Day parades. I wanted to offer them a glimpse of the other side of the capital – the squalid underbelly; a Delhi that one wouldn’t find in the glossy pages of tourist brochures. I wanted to portray the dark side not because I liked those areas but because I felt that as a writer I had to portray the truth… to hold up a mirror to society, so to speak," he explains.

Simple language

Writing in a lucid style "in simple language so it would appeal to all", Mukundan spent close to two years working on the book, which went on to become a regional bestseller. "The first edition sold some 10,000-plus copies in the first year," he says.

Keen to know more about his creative process, I ask the celebrated writer, whose Mayyazhi Puzhayude Theerangalil (On the shores of the Mayyazhi river, 1974) is arguably his masterpiece that brilliantly portraits the political and social background of his hometown Mahé, whether he follows any writing rituals.

"For one, I use a fountain pen," he says, excited to discuss the writing process. "I enjoy hearing the faint scratching sound of the pen moving over paper. It kind of inspires me. A ballpoint pen doesn’t give me the same feel."

He admits that writing long hand can be a challenge when it comes to editing and rewriting, particularly when the novel extends to some 500-plus pages. "Making corrections would mean having to rewrite everything afresh."

Hoping to make life easier, some years ago he took the advice of a friend, invested in a laptop and spent a few weeks learning to use it. "But when I sat down to write, I wasn’t able to type a single word. Absolutely nothing came to mind. My creative juices just froze."

The award-winning novelist spent three days staring at the screen before giving up and returning to his beloved fountain pen and paper. "I’d been using the pen for 40 years so I guess I couldn’t change that habit overnight."

Now he writes a few pages, enters what he has written into the computer, repeating the process before revising, editing and finalising his work on the laptop. "So, yes, it has helped speed up the process and saves me time," says the 78-year-old.

‘Characters screaming in my head’

Time, or rather the lack of it, though, has always put a crimp on his creative endeavours. He admits that although his job at the French embassy kept him extremely busy – he frequently worked even on holidays – he enjoyed his job. "It was a lovely place to work at; while the responsibilities were enormous, you also enjoyed some benefits like the option to work from home on some days."

Mukundan would wake up around 4am, make himself a cup of tea and start writing. The plan was to write for a couple of hours, then head off to office. "But the problem when you are writing a novel is that sometimes you get so involved in it, you forget everything," he says. "The characters begin to haunt you. I’d hear them screaming in my mind, urging me to tell their stories… to put their tales down on paper. It was a struggle to control them; I couldn’t tell them ‘I don’t have the time’."

So Mukundan would use his lunch break to pick up from where he’d left off. Stepping out of office, he’d hop into his car – a small Fiat – drive around until he found a quiet, deserted alley, park by the kerb and start writing.

However, those literary getaways didn’t last long. "You see, the place where I used to stop and write were ‘highly sensitive’ as they housed residences and offices of senior government officials; apparently cops were monitoring my movements." One day, a couple of police officers pulled him up. "They said they’d spotted me driving by every afternoon, parking in a desolate area, taking extensive notes, then driving off after a couple of hours. They found it very suspicious," says the writer, with a laugh.

Although not convinced that he had chosen the place for some quiet to pen his novel, they let him go with a strict warning not to repeat it.

Not one to give up, Mukundan changed his location but was nabbed again. "Luckily it was a different set of officers or I’d have been carted off to the station," he laughs. Not keen to take any more chances, he decided to write from home.

Do you miss Delhi? I ask the celebrated novelist.

"Yes, there is a certain nostalgia," he confesses, adding India’s capital has seeped into his core. "I grew up there and it grew on me. When I was in Delhi, I was nostalgic for my home in Mahe. Now it’s the other way round, but I have every intention of staying here."

If Delhi offered the writer views of its underbelly, it also left him with several pleasurable moments. "Once in office, I bumped into Regis Debray, [the French philosopher and author who fought alongside Che Guevera in Bolivia in the 60s] and ended up having a long chat with him."

A novel in the works

Nearly a decade since the publication of Delhi Gadhakal, is he considering another book on the capital city? I ask.

"Yes," he says, excitement rising in his voice. "But it won’t be only on the city. Rather, it’ll be on my life in the embassy but I’ll connect it to the present day Delhi."

That said, he accepts that age is catching up. "Writing requires a lot of energy and the problem is I’m not young any longer. My mind is young, but when I look into the mirror, I realise I’m not," he says, laughing.

Something like the spirit is willing but…, I chip in.

"Yes, yes, yes," he agrees. "You can say that."

Has this stay-at-home period left him with more time to write?

"Not really," says Mukundan, a veil of sadness cloaking his words. "I used to believe that when I retired, I’d be able to spend a lot of time writing. But I now realise I work better under pressure. Maybe the times are also to blame; it’s so depressing that one doesn’t feel like taking up the pen."

I ask him to share this thoughts on the virus.

"I like to call this a socialist virus," he says. "It doesn’t discriminate between the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak. The British prime minister was affected by it; then [Donald] Trump. In India, the powerful [home minister] Amit Shah got it."

The author is sure that the devastating virus will trigger a major pandemic novel. "Remember, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land was written in the aftermath of the Spanish Flu. [Albert] Camus’ The Plague followed an outbreak of plague… all pandemics were followed by great literary works," he says.

So can we expect a book from him?

"My problem is that I cannot respond to issues and events immediately," he says, underscoring the reason his book on Delhi arrived decades after incidents he mentioned in it occurred. "I don’t believe in knee-jerk reactions to events. I don’t believe one should respond instantaneously to things. But that is the way I am.’

On the translation

Mukundan is pleased that with the translation, his work can now be read not just by those who know Malayalam. "Translation is no easy task. It is technical and creative," he says. Heaping praise on the translators, Fathima EV and Nandakumar K, he adds: "I couldn’t have hoped for a better team or a better publisher."

Fathima, an award-winning translator and writer based in Kerala, and Nandakumar, a former journalist and now a senior manager of a firm in Dubai, spent close to two years working on the translation. "To me, a translation is something that expands the scope of a book and ensures it is read by a large number of people," says Fathima, a published poet and the principal of the Women’s College in Kannur, Kerala.

Being a team effort, the duo admit there were differences in perspectives when it came to what a translation ought to be. While Fathima considers it as a creative interpretation, Nandakumar believes a translator should only render the author’s work faithfully in another language. "I don’t believe in trying to transcreate or read between the lines of the original and add my inputs to the translated work," he says. "I stick as close as possible to what the writer has written."

For Fathima, who admits she enjoys translating verse more than prose, Delhi was a fascinating book "in that it was a retelling of history in some way – it was filling in the gaps of what was the commonly told history of the city and the country.

"The fact that the author and I hail from the same place meant localised usages and dialectical variations were rarely a challenge. I truly enjoyed the collaborative process."

Nandakumar, the grandson of one of Malayalam’s most respected poets, Mahakavi Vallathol Narayana Menon, agrees. "We worked perfectly as a team; the four of us including Mukundan and Karthika, the editor at Westland. The original draft had pages and pages of footnotes, but Karthika reviewed it and felt footnotes should be minimal. So in the end, they were reduced to two or three. I think that worked perfectly."

Delhi: A Soliloquy is available on Amazon.com