Confessions of a wildlife film-maker: ‘I thought I killed David Attenborough!’

Author and Emmy award-winning cameraman Gavin Thurston tells Anand Raj OK about the time he thought he had killed David Attenborough, his close brushes with death in the wild and why he thinks the pandemic might benefit nature

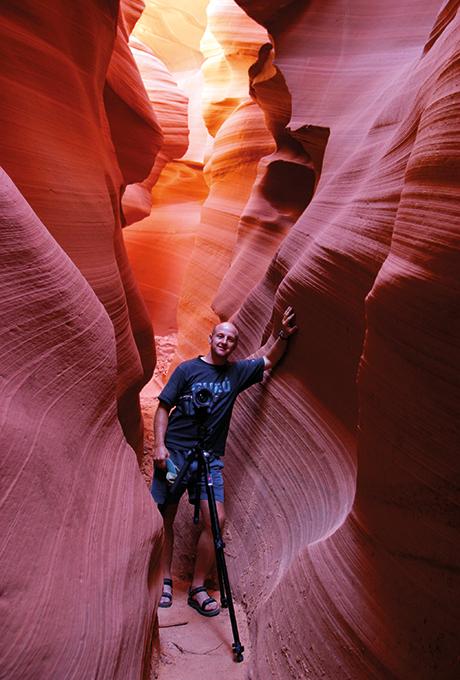

Award-winning cameraman, bestselling author and wildlife specialist Gavin Thurston may have won five Emmys, a couple of Baftas, captured footage of the extremely rare Sumatran tiger in the wild and eyeballed mountain gorillas, grey wolves and brown bears from as close as four metres. But ask him to recount (and believe me, he’s a brilliant raconteur) a memorable moment of his life, and he will tell you it’s the time he was convinced he killed Sir David Attenborough.

The Briton who has worked on 18 of Sir David’s wildlife series and who considers the legend one of his mentors, recalls the time he was “serving” on an Attenborough series called The Life of Birds. “We were in the Galapagos,” he tells me, in an exclusive telephone interview from his home in London. “We’d film early in the morning, late in the afternoon and late in the night when bird activity was good,” he says. “During mid-day, we’d go ashore and stay out of the heat.”

One afternoon while in their little cabin during a break in filming, David was busy on his computer working on his book while Gavin, seated a little away, a set of headphones plugged into a Walkman, was listening to a compilation of Monty Python songs.

Taking a break from writing, David asked Gavin if he could listen to the songs for a while. “I passed the headphones to him and after 10 or 15 seconds, David started chuckling, then laughing uncontrollably before he keeled over sideways and disappeared under the table near the bench he was sitting on.

For a moment, Gavin was terrified. “I remember saying to myself, ‘Oh my gosh, I think I killed David Attenborough!’’’ he says.

Convinced David had had a heart attack, Gavin rushed over to the side of the table only to see the legendary wildlife film producer lying on his side roaring with laughter over the songs’ lyrics.

What did you do? I ask him.

“Nothing,” says Gavin. “I was just so glad that I hadn’t killed him.”

Gavin, who was in Dubai earlier this year to speak at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, has just published Journeys in the Wild: The Secret Life of a Cameraman with a foreword penned by the man he believed he nearly killed.

The book was scheduled for publication earlier this year but Covid-19 played spoilsport. Gavin admits that the pandemic has thrown a spanner in a few of his other projects as well. “But I don’t feel too bad about it because everyone is almost on the same boat,” he says, then after a pause adds: “Wildlife and nature will have time to recover from the previous decades. When I do get back into the wild, it’s going to be nicer.”

It perhaps already is. The 58-year-old is already noticing changes around his home in the UK. “The air is filled with bird sounds all through the day; you can hear the wind in the trees because there isn’t much traffic or aircraft noise. That’s the positive side to this virus. The downside, though, is not great at all.”

The fact that the pandemic has put a crimp on his travel plans must surely be one of the downsides. Named by Conde Nast Traveller as “one of the 50 best travellers of our time”, the father of two has photographed wildlife in some of the most stunning regions of the globe – chimps in the Congo, marine life in Antarctica, wildebeest in Africa, birds in the Himalayas…

He has had his camera lens bitten off by a Siberian tiger, slapped by a silverback gorilla, peered down the Nogronggoro Crater in Tanzania and followed grey whales from the Bering Sea in the Arctic to the lagoons of Baja California in Mexico. But travel-weary he is not – his almost child-like enthusiasm and excitement for nature is still palpable when he talks about the various film projects he has worked on.

A world record holder for the deepest dive in Antarctica while filming Blue Planet 2, Gavin says one of his most memorable moments was seeing “my first whale in the wild – a grey whale, the size of a school bus swimming towards me”.

Coincidentally, it was an Orca whale that he captured on film way back in 1972 while on a school trip to Windsor Safari Park (now Legoland) in the UK that led him to choose filmmaking as a career. “I still have that picture,” he says. “And I still remember the moment I pushed that camera button. It’s etched in my mind.”

Leaving school at 18, he landed a job in a small film company where his passion for photography developed. His first “professional assignment” though had little to do with film-making. “I started off as a professional floor sweeper at the film company,” he says, with a laugh. “I realised early that if you are going to get into the film industry you need to start at the bottom.” Moving up the ladder quickly, a few years later he landed a job at the BBC where he became assistant cameraman to several stalwarts in the field of documentary making. “I have not stopped learning since,” he says.

Over the years, Gavin has had over 250 camera credits on British television, including for Planet Earth 1 and 2, Africa, Frozen Planet, Human Planet and A Monkey’s Tale.

Clearly, one of the people who had a huge influence on his professional life was David Attenborough. “The first time I saw David was on a TV serial called Life on Earth, a blockbuster series some 40 years ago. I watched the series not because I was particularly interested in wildlife at that time but because it was a good excuse to stay up late because I was at a boarding school.”

Barely a teenager, Gavin remembers being captivated by the “amazing storyteller so passionate and clear about his storytelling”.

The first time Gavin would meet David would be when he was working on a series called the Trails of Life. He remembers being incredibly excited and nervous to meet the iconic figure. “I shook his hands and said ‘Nice to meet you Mr David’, and he looked a bit ingratiating and straightaway said ‘You can call me David’.”

It’s a relationship that has endured to this day with Gavin working on several of David’s projects, including the most recent one – Life On Our Planet. And the latter has high praise for him: “[Gavin] has endless patience and that invaluable and extraordinary ability to anticipate what an animal is about to do before it does it, so that the camera is immediately ready to follow it. But now I realise he has one talent I had not previously suspected. He is a vivid writer with an ability to describe scenes with great economy and unflinching accuracy,” wrote David in the foreword to Gavin’s book Journeys in the Wild.

So, does Gavin believe environmental photography should be beautiful and picture postcard pretty or raw and rugged?

“I think there’s space for all types of environmental photography,” says the award-winning cameraman.

Different techniques may be required to drive home the point to different viewers. “Some need shock and horror – pictures of elephants with their tusks chopped off or a rhino with its horn hacked off by an axe. Others may need a softer approach. You need a whole raft of styles to point out the [damage we are doing to the planet] or to drive home a message,” he says.

Choosing the right technique apart, the challenges of capturing footage have changed over the years. Earlier it was technical – whether one had the right lenses, adequate stock of raw film or the appropriate camera. “Now the greatest challenge is not technical. It’s climate change,” says Gavin, who has filmed in all seven continents and both the Poles.

“Earlier, we had set seasons… like the short and long rains in Africa would start on March 15 and November 15 and that would be pretty much to the day. But climate change has thrown all that into turmoil. Sea temperatures are rising, ocean currents and nesting periods are changing, seasons fail or come early… where there was once some predictability that has gone now.

“We go to Africa in March and expect the short rains and the wildebeest migration [to happen] but if the rains fail, there is no wildebeest to film!”

But how can one prove to all of those people who are still in denial of climate change that the phenomenon is real and worrying and needs to be tackled urgently, I ask the man who has been documenting nature for over three decades.

“The thing is if you were to visit Alaska today and see a glacier, you will find it beautiful. What you wouldn’t know is that it is perhaps three miles shorter than it was 30 years ago. So it’s not obvious,” he says. “To get a good idea of climate change all you need to do is a compare images of a particular glacier in Alaska to how it looked 30 years ago and how it looks now.”

Another way is to look at deforestation or how the planet is littered with plastic. “That’s why the Blue Planet series has such an amazing influence on the world. People were so struck by the damage we are doing with the plastics that is ending up in oceans. It has helped change the culture a bit, at least in England,” he says.

“Even I have changed. Earlier I used to go to the supermarket and use a plastic bag for my purchases but now I probably get one plastic bag in a year out of necessity and I make sure I use that bag as many times as I can.”

People’s attitude to plastic has changed, he says. “And I think that it’s because it is very obvious to us. If you go to a beach you will see discarded flip-flops and bottle caps and bags and all sorts of plastic debris, and I think it is easy to react to that because it is the most obvious thing. But climate change is not an obvious visible thing, it is something that has happened slowly over the course of time and is now accelerating.”

Changes in photography

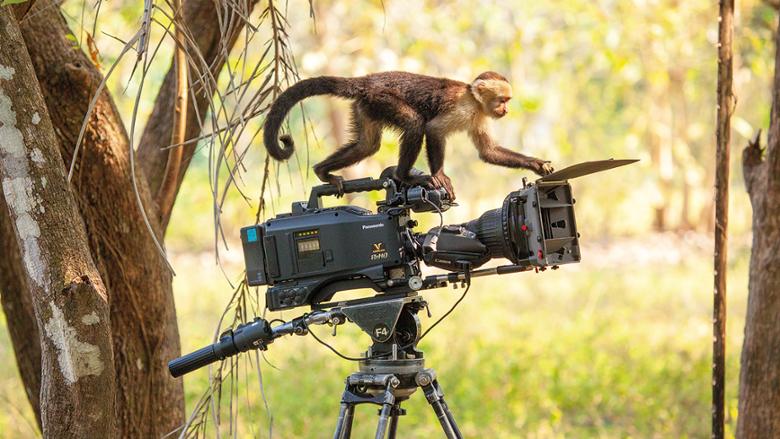

In keeping with the changes happening around the world, wildlife photography too is morphing. Gavin admits it has become more cinematic. Taking a leaf out of Hollywood filmmakers’ books, wildlife filmmakers are adopting strong narratives treating animals as characters “so you engage with not a herd of wildebeest but with one specific wildebeest, maybe one with a missing horn. Instead of filming a herd of elephants, you choose one particular elephant, or one particular snake, and follow it.”

He, however, makes it clear that this style is not new. “Disney did it for decades with its wildlife films.” Remember Lassie the dog, Flash the otter and many more. “Only now has it been reapplied and looked at in a more clever way to engage the audience.”

As we come to the end of the interview, I ask Gavin to tell me about the time when he was in the greatest danger while photographing wildlife.

“All my close shaves with death [while working] have all been due to human error – be it an aircraft crashing due to failed engines, or because of a short runway or once nearly crash landing a helicopter in Antarctica due to pilot error, or caught up in a civil war like when I was in Panama in the 90s.

“The few close encounters I’ve had with wildlife were all due to my stupidity,” he says, with a laugh.

“All the close shaves I’ve had were due to my or my associates’ errors in some way or my stupidity. If I was trampled by an elephant or charged at by a rhino, I’d hold no grudges against the animals; it would be my own stupidity that would have caused that.”

What lessons has he learnt from his journeys and work, I ask.

Gavin takes a moment to answer. “The biggest lesson is that we see humans as a violent species with wars and turmoil. But on a one-to-one basis, humans are generally kind people.”

Gavin’s tips for wannabe environment photographers

• Watch what you want to do, and if you are able to step out do it.

• Read photography books, watch programmes, but the most important thing is get out and do it yourself. There is only so much you can learn by watching other people doing it. You need to get hands-on. It doesn’t matter if it’s your phone or a regular camera; the key is to get out and do it – over and over again.

• The good thing about photograph now is that you can take a picture and see it right away. In my times, we had to wait for two weeks before we finished the reel and developed the pictures. And then you had to remember what you did wrong and try to correct it the next time.

• You need to take your time when shooting wildlife and nature. Nothing happens quickly. Take time to observe the things that are happening to the birds, the bees, the animals... It’s amazing to see what they do. The more you watch one species the more you will be drawn in the subtle things they do.