Pat Barker: We’re at the end of patriarchy

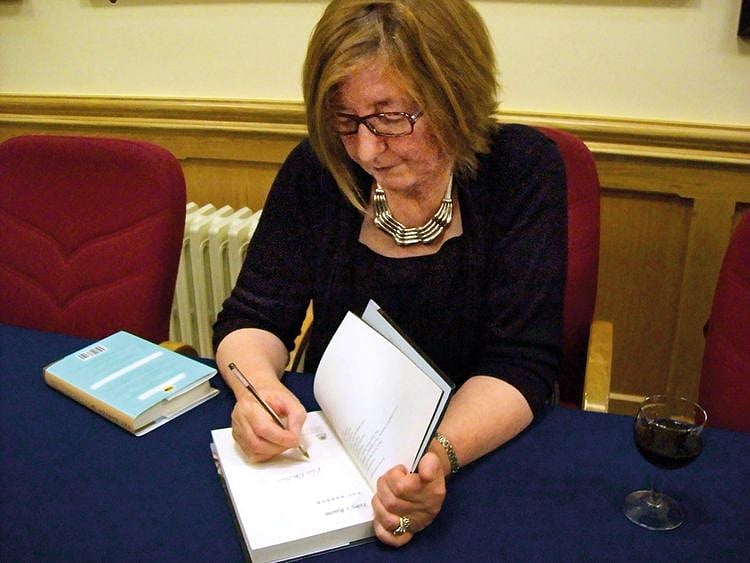

The English novelist on Brexit, #MeToo and rewriting the Iliad from a female perspective

Pat Barker is sitting in a Durham pub, making a back-of-an-envelope list of all the myth-related books that have been published in the last couple of years. There are 11 so far ranging across fiction and non-fiction and she is particularly taken with an Odyssey-based memoir by Daniel Mendelsohn, which points out that, for all its derring-do, the Homeric epic revolves around a bed (the one to which Odysseus returns and Penelope has kept warm, accepting him back as her husband only when he recognises it as “a living tree”).

Barker’s contribution to this growing subgenre is The Silence of the Girls, which looks at Homer’s other epic, the Iliad, from the vantage point of the enslaved Trojan queen, Briseis. One of four books in contention for the Costa novel of the year, and with a film deal just signed, it has been widely acclaimed as a triumphant departure from her familiar stamping grounds of the First and Second World Wars. “It’s the first time I’ve had a group of women sitting together over a dish of wine talking about what men are like in bed,” she says. To put it bluntly (as Barker’s women do), Agamemnon prefers “the back gate” and Achilles is “quick”.

The novel is set during the siege of Troy, as the Greek army builds up to its final assault, surrounded by the “sex slaves” captured in its previous victories. Though the story hasn’t been updated in any overt way, her Greek and Trojan women are gossiping all around us in the homely north of England pub. As she says of her characters: “They are very north-eastern — and why not? It’s about toughness, irreverence, humour and bitterness all thrown in together.”

Take away the bitterness, and the 75-year-old novelist could be describing herself. “In my personal life I think you’d say there have been a number of prominent women,” she says. It was the storytelling of her working-class grandmother and great-aunts that taught her about the richness of contested history. “They would argue passionately. One sister believed her father was a drunkard, another believed equally strongly that he never touched a drop.”

While insisting that the inspiration for the novel “certainly had nothing to do with the #MeToo movement, which didn’t become a trending story until after it had been sent off to the publisher”, she recognises that there is a synchronicity in the proportion of female novelists who appear on the back of her envelope. “As to why so many women are turning to those stories at the moment I don’t know. You could think of half a dozen reasons, some optimistic and some non-optimistic,” she says. “We’re bombarded with ephemera. One day a book is top of the bestseller list and six months later you struggle to remember its name; these [classical] stories are thousands of years old. There is an appetite for things that have stood the test of time as our lives change so rapidly. They have an agreed significance, even if we don’t agree on what that significance is.”

But as she thinks on, she wonders if something more profound might be going on too. “You could also say that as people get near their end they return to the beginning. It’s a way of trying to make sense of their experience, but that raises the question of what we are coming to the end of.” Half of her 14 novels have dealt with the fallout from the First and Second World Wars. “You could argue, and perhaps it is true, that time’s up: we’re at the end of patriarchy, and I’m fine with that as long as it’s remembered that among the victims of patriarchy the vast majority are men.”

Brought up “on the pancrack” (national assistance) on Teesside by her beloved grandmother, her personal experience of the domestic catastrophe of warfare was fortuitously limited. Her step-grandfather had a bayonet wound from the First World War and her father “is supposed to have died in the Second World War, though I don’t think anybody can be sure what happened because nobody knew who he was. But my mother always presented herself as a widow because it was a terrible shame to have a child without a father.”

As to her interest in the wars of antiquity, “I’d have said it only goes back four or five years, but somebody pointed out to me that in Life Class [the 2007 novel that began her second wartime trilogy] there’s a passage in which Elinor Brooke is writing to Paul describing what’s going on in the early days of the First World War and she says it’s exactly like the Iliad. So obviously I must have read it at that point though I didn’t know that I had. I had no classics background. But a writer doesn’t know how far back the germ of a book goes.” She says the inspiration for The Silence of the Girls “probably goes back to early childhood — though I can’t remember being a very silent child.”

Elinor’s letter turns out to foreshadow her latest book to an uncanny extent. Describing what it is like in London’s once glamorous Cafe Royal, which she and Paul used to haunt with their art school set, she writes: “Now it’s full of frightened old men who think their day is over (and they’re probably right) and overexcited young men who jabber till the spit flies, though it’s only stuff they’ve read in the paper. The women have gone very quiet. It’s like the Iliad, you know, when Achilles insults Agamemnon and Agamemnon says he’s got to have Achilles’ girl and Achilles goes off and sulks by the long ships and the girls they’re quarrelling over say nothing, not a word ... I don’t suppose men ever hear that silence.”

A paradox of The Silence of the Girls is that Barker’s excavation of that silence has brought her back to the loquacious, female-centred worldview of her earliest work. Union Street (1982), Blow Your House Down (1984) and The Century’s Daughter (1986) were all set in the north-east and published by the feminist imprint Virago. By the end of the decade she was feeling claustrophobic, complaining that she “had got myself into a box where I was strongly typecast as a northern, regional, working class, feminist — label, label, label — novelist”. Particularly irksome to her was the recurrent question of whether she could write men — “as though that were some kind of Everest”.

Her response was to leave Virago and begin work on her name-making Regeneration trilogy, which recentred her reputation in the predominantly male arena of warfare — “or more generally speaking violence, because there’s criminal violence in my work and some domestic violence too, though basically it’s about the trauma of war”. Published in 1991, Regeneration wasn’t the immediate hit it is often now assumed to have been, she points out — “most overnight successes in literature took 20 years’ hard slog” — but the second novel, The Eye in the Door, won her the Guardian fiction award and the third, The Ghost Road, scooped the 1995 Booker prize.

One of the strengths of her war writing is the unflinching eye she brings to its bodily horrors. Her novels are full of hospitals in which wounded soldiers struggle with psychological and physical mutilation. In Life Class a soldier’s attempt to kill himself leaves “his left eyeball swinging against his cheek”; in The Silence of the Girls, wounds “crackle” with gangrene (a symptom you can find today on the NHS website). But she is quick to give Homer his due: “The violence is incredibly accurately described. I do believe that late in the formation of these stories there was a single mind reshaping them and it was a mind that was very familiar with the inside of the human body: with the kidneys, the liver. He could only have learned that on the battlefield.”

But war has its longueurs too, and nowhere more so than in the Iliad, whose endless lists of dead heroes are mocked by Briseis: “As it happens I know all the names of all the men [Achilles] killed that day. I could recite them to you, if I thought there was any point.” “But ... how on earth can you feel any pity or concern confronted with this list of intolerably nameless names?”

Barker’s search for a female perspective brought her to the realisation that “of course the young men who died were husbands — and, particularly poignantly, sons”. She gifted to Briseis her belief that the stories of “common women whose names you won’t have heard” can humanise history by recalling the childhood foibles of dead heroes or the long labours their mothers suffered giving birth to them.

All the same, it was a challenge to maintain interest in the men without breaking faith with Briseis’s chilling insight that the alienation between the warriors and their captives was so complete that “A slave isn’t a person who’s being treated as a thing. A slave is a thing.” To do so, Barker counterpoints Achilles’ contempt for his concubine with his love for his foster brother, Patroclus. Their relationship is sensuously drawn. Are they gay lovers? “I have no hang-ups about writing about gay relationships, as readers of The Eye in the Door will remember, but I didn’t want their relationship to be sweaty buttocks in a tent because I think it’s much more interesting than that. There’s a presexual bond and also they’re brothers in arms, which can be very passionate, though it’s not spoken about in those terms.”

Any criticism of the novel has tended to centre on the credibility of her feminised perspective, particularly with regard to Helen, who has a spiky cameo as a style icon contemptuous of less beautiful women’s attempts to copy her eye makeup, and whose tapestries — full of men “gutted, skewered, filleted” — are described as “a way of saying: I’m here. Me. A person, not just an object to be looked at and fought over.” Barker is fiercely dismissive of such quibbles, insisting, “All the anachronisms are deliberate.” Her soldiers are prone to breaking out in bawdy ballads when drunk, “and I keep having to explain that I don’t exactly believe that Homeric warriors were singing English rugby songs either”. What, she asks, does it mean to say a character who never existed was anachronistic? “You can be anachronistic about Elizabeth I but not about Helen.”

In the Trojan war as in many others, she points out, it is women who survive, even if their voices are not reported. “It’s women who carry the can long-term; not exclusively — some men become carers for their wounded sons — but mostly it’s women, long after the politicians have forgotten.” This brings us to the great and enduring subject of doomed youth, which leaves a devastating trail through millennia of warfare and has particular resonance today, a century after the great slaughter of the First World War.

As a remain voter in a strongly pro-Brexit area, she is clear that “one side of the immense battiness of Brexit is the young feeling they’ve been done out of something by the old, which is almost more worrying than the division between London and the rest of the country, although that is also extremely deep.” A beneficiary of free education — who went from grammar school to study international history at the London School of Economics and on to a teaching job before getting her first novel published at the age of 40 — she is acutely aware of the betrayal of young people following behind her: “I doubt I’d be able to go to university today.” While she doesn’t consider herself to be a working-class writer, “in that I don’t write consciously of working-class experience in the way I once did, I always take pride in producing working-class characters who are not just there for light relief as they unforgivably are in many novels about the middle classes.”

But one unexpected side-effect of the Brexit earthquake, she believes, is that it has woken up at least some movers and shakers to the dangers of a them-and-us society. “I think publishing is more and more interested in having regional voices. So it was a shock which has its salutary side.” More generally, she is optimistic that women are claiming joint ownership of a world to which they have historically been denied access. “So yes, I think in that sense time’s up. It gives me a reason to get up in the morning, as it should every woman.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.