Eurozone cannot afford a laidback approach

Virus-led economic slowdown is a real risk for bloc, for which it needs instant solutions

(Bloomberg): An infection typically hits the vulnerable hardest - and in the new coronavirus outbreak this might apply economically too. For all the geographical distance between Europe and China, the eurozone has much to fear from its spread.

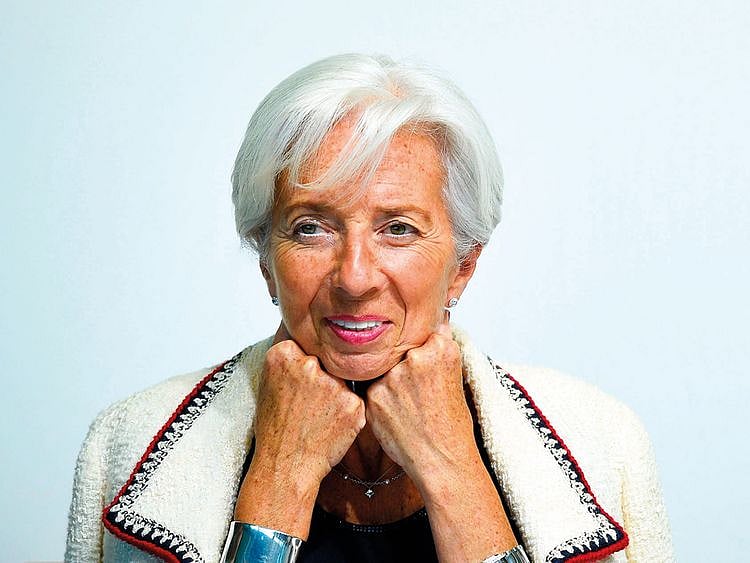

The disease is another challenge to the export-driven model of the monetary union, which was already struggling with the global lurch towards protectionism. It could be the first big test for Christine Lagarde, the European Central Bank’s new president, who has been a tad too optimistic about the euro area’s prospects.

Hardest hit

Coronavirus will affect Europe’s economy in three ways. First, there’s demand: China is the third-largest importer of goods and services from the eurozone, after the US and the UK. The bloc’s exports to China nearly trebled between 2007 and 2018, to 170.3 billion euros ($185.8 billion) from 60.5 billion.

Over the same period, sales to the US increased by about 63 per cent. These figures matter because Europe relies extensively on global demand to drive its prosperity, as shown by its large external surplus. A slowdown in China sales will cause trouble in a number of industries such as luxury.

Then there’s supply. Europe’s manufacturing supply chains are less exposed to China than is the case for other regions of the world, according to a report by Oxford Economics.

However, it notes that some industries might be more exposed: The Wuhan area, where the virus originated, is a major automobile hub and home to production sites of carmakers including Peugeot and Renault.

Confidence sapping

Finally, there’s the effect of the outbreak on confidence. Europe’s financial markets have been resilient so far: The Stoxx Europe 600 index is still marginally up since the start of the year. It’s possible some companies will benefit from the disruptions, as producers have to look for alternative suppliers.

However, coronavirus could weigh on investment decisions in the eurozone. An investment slowdown would create long-term economic damage, even if supply and demand in China rebounded quickly.

True for all, yet

These factors matter for every economy in the world, not just the eurozone. But the monetary union’s economy is already very weak. Growth slowed to just 0.1 per cent in the last three months of 2019, the worst quarterly performance since 2013.

From Germany to Italy, the industrial sector had a terrible end to the year. Unemployment continues to fall and wage growth remains solid, which should support internal demand. However, the euro area has been exposed to a succession of external shocks.

The longer the coronavirus episode lasts, the higher the risk it spills into the domestic economy.

The ECB is yet to react, and is still in wait-and-see mode after cutting rates and relaunching quantitative easing in September. Lagarde had even dropped some hints of optimism over inflation, which has stubbornly stayed well below the central bank’s target of close to but below 2 per cent.

Inflation isn’t about to rise

The waiting game may not last for long. As well as holding back growth, the virus may also force inflation down too. Oil prices have plummeted because of the slump in demand from China. The OPEC+ group of oil-producing countries is struggling to agree a new cut in production to help support prices.

The eurozone mostly imports crude, so in theory any fall in its price should be good for its economy: Consumers would have more cash to spend on other goods, and companies would see their energy bills fall. In any case, central banks usually prefer to look through changes in energy prices and concentrate on “core” inflation.

A year on the brink

Yet the memories of 2014-15 linger in the mind of policymakers. A sharp fall in oil prices at the time contributed to a bout of deflation, which threatened to turn the eurozone into Japan. In response, the ECB launched - for the first time - a programme of massive and unconditional bond purchases.

Unfortunately, this time around the ECB has already used several of its weapons to combat deflation. The balance-sheet of the Eurosystem - made up of the ECB and national central banks - has hit nearly 4.7 trillion euros. The ECB has pushed its main refinancing rate to zero, and its deposit rate to -0.5 pe rcent.

“This low interest rate and low inflation environment has significantly reduced the scope for the ECB and other central banks worldwide to ease monetary policy,” Lagarde said last week.

This slightly defeatist language contrasts with Lagarde’s more pugnacious predecessor, Mario Draghi, who left the ECB with the words “never give up”. It’s also as worry that the eurozone governments with low debts, including Germany, seem to feel no pressure to relax fiscal policy sufficiently to combat the slowdown.

It’s still possible that the economic threat from the coronavirus will fade. A strong policy response in China could create additional demand, which would help foreign companies.

But the eurozone’s poor state doesn’t leave room for error. After a quiet start for Lagarde, the difficult decisions could be fast-approaching.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.