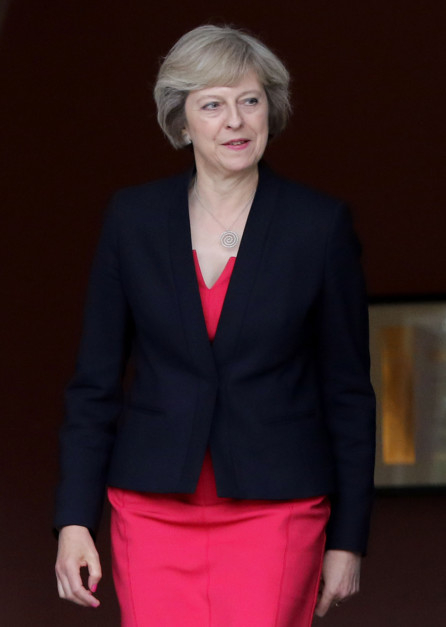

The Blair-Cameron era of leadership ended on Wednesday July 20, 2016, just before lunchtime. At her first prime minister’s questions, Theresa May presented herself with a confidence as unexpected as it was ruthless. Last week I argued that the new PM must dissuade the political fantasies of those Tory MPs who, in ideological projection, would cast her as the “new Thatcher”. It now appears that she is more than capable of handling such expectations.

Rummaging around in the dressing-up box of the political past, she had evidently found the wig and the handbag and thought: “Why not?” In answer to a question about “unscrupulous bosses”, she turned the tables on Jeremy Corbyn thus: “A boss who doesn’t listen to his workers. A boss who requires some of his workers to double their workload. Maybe even a boss who exploits the rules to further his own career.”

Then, the menacing lean towards her opponent: “Remind him of anybody?” In the first instance, of course, what she meant was that the Labour leader himself was an “unscrupulous boss”. But she was also addressing the Commons, the political class and the viewers: “Do I remind you of anyone?”

It is perhaps no coincidence that a YouGov poll published on Friday by the Independent suggested that the public considers May to be stronger and more decisive than they judged Cameron to be after the first few days of his premiership in 2010. These are whispers of opinion, grainy snapshots of the political weather. The true tests lie ahead: internal party turmoil, international security crises, serious economic pressure. What is certain, however, is that Prime Minister May is not going to be the grey, bloodless technocrat of collective expectation.

This is not to say that Thatcher stalks the land once more, or that May proposes to govern as a tribute act. What her first days in the top job suggest is that she no longer feels constrained by the leadership norms that have been in place for 20 years or so. The end of the cold war shone a brighter spotlight than ever before on politicians’ personality, character and values. Bill Clinton and Tony Blair personified the new importance of empathy and, in their case, radical informality (“Call me Tony”). George W. Bush’s handler, Karl Rove, posed the core question thus: which candidate did the voter most want to have a beer with?

Blair’s familiarity with his colleagues and the public was turbo-charged by the laddish football culture of Euro ’96. His “emotional intelligence” flourished in the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death. Gordon Brown, on the other hand, was never at ease with this form of leadership, charismatic, relaxed and “pub-ready” (remember how the nation’s toes curled over his supposed love of the Arctic Monkeys?). But David Cameron revelled in it, affably chatting with interviewers about Angry Birds, Game of Thrones and his favourite recipes.

Long before she became prime minister, May had decided that being a party moderniser — consistently and often bravely — did not mean surrendering the authority of high office or assuming a bogus familiarity. She preferred to keep a friendly distance. Is it too reductive to note that Blair and Cameron went, respectively, to Fettes and Eton, schools that nurture preternatural confidence and silken informality in their pupils? Is it a coincidence that Brown and May are the children of clergymen, less inclined to ditch ceremony and to treat everyone, instantly, as a best friend and confidant?

Above all, May understands the curious attitude of the Conservative party towards women. In a pathology that would delight Freudians, its worst reactionaries perceive the ideal woman either as a passive creature or as a terrifying dominatrix — and not much in between. The party has come a long way, but still has a long way to go. Of its 330 MPs, only 68 are women. Of the 22 cabinet posts, including the prime minister’s, eight are filled by women — Amber Rudd, at the Home Office, holding a great office of state. Thatcher, in sharp contrast, did little to advance the position of women in government.

In the second volume of his magisterial biography of the Iron Lady, Charles Moore quotes Carla Powell, a friend of Thatcher, whose husband, Charles, was her closest confidante. She could, Powell recalls, be “totally, utterly ruthless”, and once advised her: “Carla, if a woman takes on a battle, she has to win.”

Moore also cites the view of John Coles, Thatcher’s foreign affairs private secretary from 1981 to 1984, that her male colleagues in cabinet drew “on a reserve of accepted thought and behaviour, of male humour, argument and sign language from which a woman is excluded”. It followed that an ambitious woman had to be doubly tough to survive and prosper.

Westminster has become more enlightened, but I suspect May believes this still to be essentially true. There must have been times in the past six years when she too felt herself surrounded by public school boys speaking a private language that, in the case of Cameron and Nick Clegg, transcended party boundaries. When one looks back, her strategy seems as smart as it was straightforward: to let the Bullingdonians and the Notting Hill set tear one another to shreds and wait patiently until, like Fortinbras, she stood triumphant on the stage, surrounded by dead bodies.

In fact, a more precise analogy would be the scene in science fiction movies (including, aptly, the new Independence Day) when a terrifying “queen” alien is revealed, 100 times more deadly than her smaller male guards who are only too glad to sacrifice themselves to protect her. Only a few weeks ago the ever candid Ken Clarke described May as a “bloody difficult woman”. Since then she has stormed into office, is beginning to settle in and — for now — has complete control of her government.

For a party supposedly in favour of a smaller state, the Tories really do like the smack of firm leadership. This PM offers compassionate conservatism to the electorate, and sharp claws to her enemies. There are structural flaws in her position — a small majority, Brexit, economic vulnerability — but May has ended one era of leadership and launched her own. When her enemies come — and they will — they should remember that this prime minister bites back.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Matthew d’Ancona is a visiting research fellow at Queen Mary University of London and author of several books including In It Together: The Inside Story of the Coalition