Settling the Bhutto 'score'

Farhan Bokhari writes: Conspiracy theories insist Zardari's decision to reopen the case is aimed at diverting popular attention

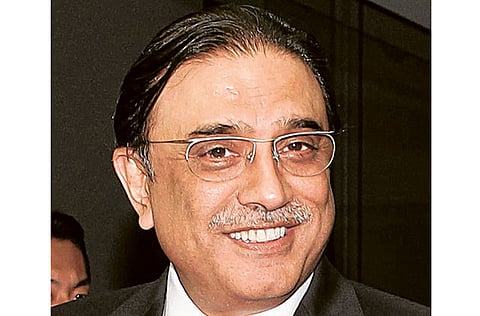

Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari took the unexpected step of formally approving a review of the court proceedings that led to the hanging of his father-in-law and former president and prime minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, in 1979, in a move that will inevitably remind Pakistanis of their country's past.

Following the signing of a formal presidential request by Zardari, Pakistan's federal government has put in motion a process whereby the country's supreme court has been asked to revisit the case of Bhutto.

Bhutto was arrested after a July 1977 coup, led by the late General Zia-ul Haq, slapped with charges of murder that have since been disputed by many legal experts, and eventually hanged following verdicts by a provincial high court and the country's supreme court.

At the time of his trial by a three-member judge of the Lahore High Court, Bhutto's supporters took exception to what they considered a clear bias in proceedings against him.

Subsequently, the Supreme Court upheld a death sentence handed by the Lahore High Court, though the Supreme Court's verdict was split with three lawyers standing in Bhutto's favour while the other four were against him.

Zia ruled for more than a decade after the coup and eventually died in a mysterious plane crash in 1988 — the cause of which to this day remains surrounded by many conspiracy theories. But for more than three decades since the late Bhutto's hanging, anecdotal evidence shared by Pakistanis generally points towards glaring gaps in the way the prosecution process was pieced together.

While the trial progressed, human rights groups at the time pointed towards reports of pressure applied on judges to influence them to adopt a position against Bhutto's defence.

As the trial went on, an unprecedented reign of tyranny was unleashed across Pakistan. Under Zia's orders, workers of Bhutto's Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) were targeted by the military regime, subjecting them to a variety of harsh punishments, ranging from simple imprisonment to lashes being applied in public.

More than three decades later, across Pakistan, conventional wisdom says much about how Zia's methods and his position badly backfired.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that justice was not served and Bhutto bore the brunt of Zia's brutal force. His hanging deeply divided Pakistan and left a scar which to this day continues to split the country.

Fault lines in the system

Fissures all too obvious within Pakistan's political system notably include the popular view across the southern province of Sindh — Bhutto's home turf — where most people on the streets believe that his hanging did not serve the cause of justice.

In this background, a powerful and compelling question indeed relates to exactly why Zardari has moved at this time to seek the reopening of an old and a deep wound.

Last Friday, government leaders said, they were principally driven by their yearning to press ahead in setting right what they believed was a blatant historic wrong. If a Supreme Court review of the case is followed by a reversal of the 1979 death sentence, Zardari and the PPP will have good reason to feel amply vindicated.

Yet, the conspiracy theories of the day also continue to insist that the move is driven mainly to divert popular attention from a number of key issues that are well beyond the government's control.

On the face of it, it is impossible to draw a conclusion on the lines of a self-serving intent.

But what is indeed vital is the fact that Bhutto's fate led to the derailment of what could have become a state of progressive democracy in Pakistan.

To this day, he remains the only prime minister who served his full five-year term, but was hanged just two years later on what many consider to be flimsy charges.

For Pakistan's coming generations, Bhutto's hanging will always remain a sorry affair that the country could have done without.

Obviously, it is not possible to undo this dark chapter in Pakistan's tragic history. But what is indeed possible is to set in motion a process of reconciliation which in time will help Pakistan's people start filling the wounds of an unfortunate past.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.