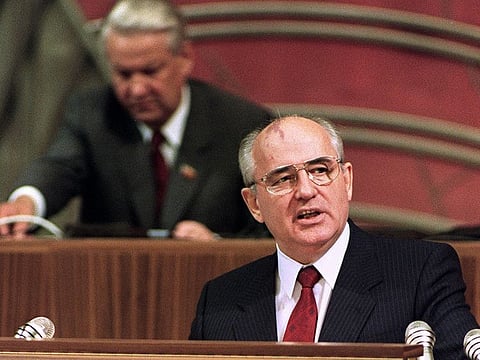

Mikhail Gorbachev — a world leader who helped end the Cold War

What made Gorbachev different was that he accepted responsibility for his action

“We all need to have perestroika,” Mikhail Gorbachev would often say. The Soviet Union’s last leader lived by that credo. After becoming the general secretary of the Communist Party in 1985 and implementing his programme of restructuring and glasnost (openness), he even changed his job title, preferring to be called president.

And in the 31 years since the Soviet collapse, his belief in peace, mutual understanding, dialogue, and democracy remained unwavering.

It was these values that led Gorbachev to withdraw the Soviet Union from a decade-long disastrous war in Afghanistan, and in 1993 to use the money from his 1990 Nobel Peace Prize to help fund Novaya Gazeta, the flagship media outlet of Russia’s democrats whose editor, Dmitry Muratov, received his own Nobel Peace Prize last year.

Along with dozens of other independent media outlets, Novaya Gazeta suspended operations soon after Russia’s “special military operation” started in Ukraine in February.

Gorbachev, too, suffered for his beliefs. Perhaps if he had died in 1991, people back then would have busied themselves assessing his place in history.

By starting perestroika, which many in Russia today, consider a disaster, Gorbachev exposed himself to criticism from every direction: for being too radical, too conservative, or too feeble. But he did not flee from public scrutiny. Even weakened by age and illness, he continued to embrace it as director of the Gorbachev Foundation, whose work embodied his values.

Like Putin, Gorbachev thought that it would have been better if the USSR had continued. But, Gorbachev envisaged a reformed federation, rather than a union of nations.

In the 2000s, Gorbachev told me why he didn’t send tanks to Germany in 1989 to prevent the destruction of the Berlin Wall (built in 1961 on the order of my great-grandfather, Nikita Khrushchev). “We shouldn’t dictate to sovereign countries their way of life,” he said.

Also Read: Mikhail Gorbachev's life in dates

Gorbachev himself was partly to blame for the antipathy he faced after the Soviet collapse. Reformers often lack patience, and his plan for sweeping economic changes in just 500 days was as utopian as Khrushchev’s 1961 promise of “developed communism” in 20 years.

What made Gorbachev different was that he accepted responsibility for the consequences of his rule. While Khrushchev and Gorbachev’s successor, Boris Yeltsin, left public life altogether, privately berating themselves for all they failed to accomplish, Gorbachev, joined historians, politicians, his own comrades, and the public in reviewing his rule. Ironically, he helped bury himself as a historical figure while still alive.

While the consensus in Russia is that Gorbachev’s reforms all went astray or failed because of his bad choices, his legacy is perceived very differently internationally. The last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of this one were the heyday of globalisation in large part because of Gorbachev’s efforts to embrace the world, establish “new political thinking”.

As a man of conscience who reflected on his leadership from outside the Kremlin, Gorbachev was eager to address the problems for which he felt responsible, including economic hardship and political instability.

Although his position was weak, his quixotic candidacy in the 1996 presidential election made casting a ballot worthwhile for at least some Russians (like me). Yeltsin’s candidacy that year, during a period of even greater chaos than the Soviet Union ever experienced, inspired very few.

It would have been a shame had such an exciting event (Russia was new to electing presidents, and the novelty imparted a festive air) become just another occasion to register dissatisfaction.

I never believed that Gorbachev had a serious chance of winning, or that he would be a good president. But he was the first president in Russian history to succeed in re-emerging as a candidate after years, able to speak as both a leader from the past and a voice for the future.

If Gorbachev did not have a chance to win in 1996, he at least had the chance to run. Perestroika and glasnost, so derided nowadays, prepared the ground for that under Yeltsin, who, while no fan of his Soviet predecessor, was democratic enough to keep the spirit of change.

In hindsight, Gorbachev’s legacy today seems to be dead. But Gorbachev himself continued to be more optimistic — till the very end.

Nina L. Khrushcheva, Professor of International Affairs at The New School, is the co-author (with Jeffrey Tayler) of In Putin’s Footsteps: Searching for the Soul of an Empire Across Russia’s Eleven Time Zones

Project Syndicate