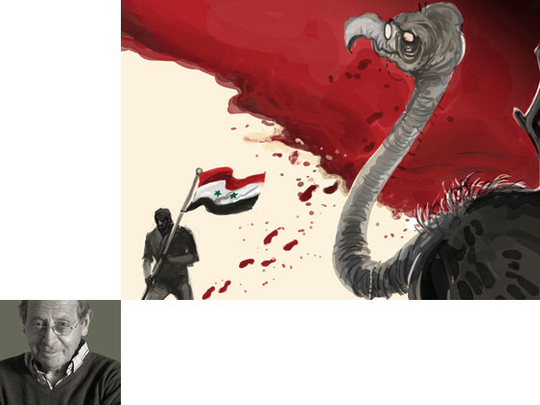

The pitiless, vengeful, blood-thirsty battle now being waged in Syria is not something new or unexpected. Nor is it a mere by-product of the Arab Spring, although events in Tunisia and Egypt have undoubtedly contributed to creating an insurrectionary atmosphere in the whole region. Rather, the Syrian uprising, as it has gradually evolved over the past 18 months, should be seen as only the latest, if by far the most violent, episode in the long war between Islamists and Baathists, which dates back to the founding of the secular Baath Party in the 1940s. The struggle between them is by now little short of a death-feud.

This is not to suggest that the present rebellion is driven only by religious motives and sectarian hate. Although these are real enough, other grievances have piled up over the past decades: the ravages of youth unemployment; the brutality of Syria’s security services; the domination of key centres of economic, military and political life by the minority Alawi community; the blatant consumerism of a privileged class, grown rich on state patronage, in sharp contrast with the hardship suffered by the mass of the population, including in particular the inhabitants of the ‘poverty belt’ around Damascus, Aleppo and other cities. These deprived suburbs are largely the result of inward migration from the long-neglected countryside, which in the past decade has suffered catastrophic losses from a drought of unprecedented severity.

But beyond all this is the decades-long hostility of Islamists for Syria’s Baath-dominated regime. Formed by two Damascus schoolmasters soon after the Second World War, the Baath party was created as a secular and socialist movement dedicated to bringing about Arab unity and independence. Schoolboy members of the party clashed repeatedly at that time with members of the conservative Muslim Brotherhood. When the party seized power in Damascus in 1963, its clash with the Islamists burst into the open. The civilian leadership of the party had by then been largely displaced by Baathist officers ‑ including Hafiz AlAssad, father of the current President Bashar Al Assad‑ mostly from minority backgrounds. In turn, these Baathist officers had allied themselves with Akram AlHawrani, the charismatic leader of a peasant revolt, which was challenging the great landowners of the central Syrian plain, most of them resident in Hama.

Hama is today remembered as the centre of the Muslim Brothers’ armed uprising against Hafiz Al Assad, which he crushed in blood in February 1982, leaving a bitter legacy of sectarian hostility. Few recall, however, that 18 years earlier, in April 1964, rioting by Muslim rebels against the Baathist regime had already flared into something like a religious war. Funded by the old land-owning families, enraged at being dispossessed, and egged on by the imam of the Sultan Mosque in Hama, the rebels threw up roadblocks, stockpiled food and weapons, ransacked wine shops to spill the offending liquor in the gutters, and beat up any Baath party man they could find.

After two days of street fighting, the regime shelled the Sultan Mosque where the rebels had taken cover and from where they had been firing. The minaret collapsed, killing many of them. Many others were wounded but many more disappeared underground. The shelling of the mosque outraged Muslim opinion, igniting a fever of strikes and demonstrations across the country.

Thus, today’s civil war ‑ for that is what it has become ‑ has deep roots in modern Syrian history. The rebellion has increasingly taken on an Islamist colouring, as the Swedish writer Aron Lund explains in an informative 45-page report on Syrian Jihadism, published this month by the Swedish Institute of International Affairs. It is striking, as he points out, that virtually all the members of the various armed insurgent groups are Sunni Arabs; that the fighting has been largely restricted to Sunni Arab areas only, whereas areas inhabited by Alawis, Druze or Christians have remained passive or supportive of the regime; that defections from the regime are nearly 100 per cent Sunni; that money, arms and volunteers are pouring in from Islamic states or from pro-Islamic organisations and individuals; and that religion is the insurgent movement’s most important common denominator.

In the last few months, the Syrian National Council (SNC) ‑ that is to say the Turkey-based civilian ‘political’ opposition ‑ has been largely up-staged by fighters on the ground. Most of these fighters are grouped into nine Military Councils (majlis askariya) of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), each Council divided into a number of brigades (kataib). But, in much the same way as these Councils have marginalised the SNC, so they also seem unwilling to take orders from the Turkey-based FSA commander, Col Riad AlAssad.

Lund points out that, with rare exceptions, the FSA is an entirely Sunni Arab phenomenon, and that most FSA brigades use religious rhetoric and are named after heroic figures or events in Sunni Islamic history. It is thought that about 2,000 non-Syrians, some linked to Al Qaida, are now fighting in Syria, about 10 per cent of the total rebel manpower, estimated at about 20,000 (although some sources put the figure twice as high at 40,000.) Most of these fighters would seem to be active only in protecting their home areas.

Three major fighting units, among a score of others ‑ Jabhat Al Nosra, the Ahrar Al Sham Brigades and Suqur Al Sham Division ‑ are among the most extreme Salafi groups in the Syrian rebel movement. The first has been linked to suicide and car bomb attacks in Syrian cities and to the assassination of pro-regime figures; the second carries out ambushes and uses remotely-triggered bombings and sniper fire against army patrols; and the third uses suicide bombers and frames its propaganda in jihadi rhetoric. The leaders of the last two have declared that their aim is to establish an Islamic state in Syria. All three seem to have welcomed AlQaida fighters into their ranks.

These fighting groups have gravely destabilised the Syrian regime but, without a foreign military intervention in their favour, they seem unlikely to topple it. The regime is fighting back with air and ground attacks, evidently determined to crush all pockets of armed rebellion on Syrian territory.

This is the conundrum facing the UN peace envoy, Lakhdar Brahimi. His task is to persuade the world community to impose a ceasefire on both sides, before bringing them to the table. But only when all are persuaded that there can be no decisive win for either side might they heed his call. In the meantime, thousands more will die or be driven from their homes and the country will sink further into blood and chaos, making the divide between the Islamists and President Bashar AlAssad virtually unbridgeable.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs