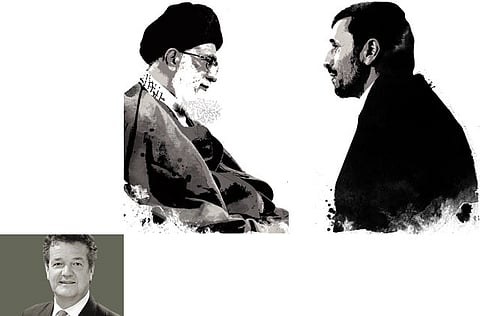

Iran president runs into trouble

The Supreme Leader has also miscalculated and his vaunted position is becoming just another political post

Iran faces a dangerous split at the top as President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei fight it out for control of government. Both favour a tough and aggressive foreign policy, but both want to gather power into their own positions. But the very existence of this struggle has changed Iran's politics for ever, since it has dragged the position of Supreme Leader off its lofty pedestal.

The position was set up by the founding father of Iran's Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei, who held a unique place in the revolution's history and a unique respect from all supporters of the Islamic Republic. After Khomenei's death, there was a vigorous debate about whether the position could continue, or whether it was a one-off position for a very special religious leader.

Those favouring continuation won, and Khamenei got the job. Although he managed to hold his distance from the day to day running of the government for many years, he has now been made part of the daily political struggle, and the position of Supreme Leader is becoming just another political post.

These tensions are set to continue for the rest of Ahmadinejad's term, as Khamenei seems to want him to finish his last two years in office. But the on-going dispute between the two means that Ahmadinejad no longer has the Supreme Leader's protection in political showdowns with the judiciary, parliament or Guardian Council.

Aggressive posture

These bodies are perfectly aware of this and have taken a much more aggressive line and have recently challenged several of the president's recent actions, including cabinet appointments, merging ministries or disbursement of state funds, says the noted commentator on Iranian affairs, Farideh Farhi.

Ahmadinejad is trying to build a future after 2012, when his final term as president comes to an end, and he is working to place his supporters in positions that will allow his ideas to continue to shape Iran. He is anxious to position one of his present supporters as a candidate for 2012, and he himself must be looking for a position that he can fill. His whole political history indicates that he is likely to resist his opponents, even if they are powerful.

The open split between the president and Supreme Leader appears to have been the outcome of a miscalculation by Ahmadinejad, who thought he had Khamenei's long-term support after Khamenei used his own prestige to support Ahmadinejad after the disputed 2009 presidential election, says Farhi.

But the alliance between Khamenei and Ahmadinejad was only a temporary marriage. Khamenei believed that if Ahmadinejad lost the 2009 election, it would be seen by the US as a defeat for the Supreme Leader's office, just as Iran prepared to start talks with Obama's new US administration.

Khamenei liked Ahmadinejad's aggressive foreign policy, unlike that of two former presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, who sought much better relations with Iran's opponents. In 2009, Khamenei found himself with the frightening prospect of a win by the much more liberal Green Movement, led by former prime minister Mir Hussain Mousavi, so he backed Ahmadinejad.

But the alliance did not work out as Khamenei has planned. He did not expect the millions of people supporting the Green Movement who took to the streets to protest at the election fraud, and he certainly was surprised that he took as much of the blame as did the president. He is expected to remain above the fray. In addition, the tough crackdown on the protestors was attributed to Khamenei as much as to Ahmadinejad.

For his part, the president also got it wrong as he assumed that Khamenei would back him all the way. But Ahmadinejad's decision to take their dispute into the public arena, and not to show up for work for two weeks offended Khamenei, who distanced himself from Ahmadinejad. This triggered renewed action against the president by Iran's many power centres.

One example of these clashes is when the Guardian Council refused to let Ahmadinejad take over as oil minister, after which Ahmadinejad appointed one of his loyalists, Mohammad Ali Abadi, a former vice-president and head of Ian's Olympic Committee as a caretaker minister.

Parliament had earlier rejected Abadi for the smaller energy ministry, but from Ahmadinejad's point of view, he now has a man in the right position to increase the president's control over the most important asset in Iran, the National Iranian Oil Company, where the oil revenues pour in.

But when his legal limit of three months as caretaker is finished, Abadi is not likely to be approved as petroleum minister by Parliament, which is also set to reject Ahmadinejad's plan to merge the energy and petroleum ministries. Ahmadinejad has also refused to establish a sports and youth ministry; and disburse money for the metro system.

If parliament felt the political situation was right, it could use these rejections of its power as the basis of a judicial review of the president, leading to questioning in parliament, and maybe dismissal.