Game of cat and mouse in Iraq

Distribution of oil wealth and the decision to shelter Al Hashemi has pitted Kurds against Baghdad

Masoud Barzani, the Kurdish leader, is a man of few words. Over the years as Iraq lurched from one destabilising crisis to the next he remained focused on his home front, consolidating his power base and let the other veteran and more senior Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani enjoy the national limelight as president of the country.

Lately, however, Barzani has been speaking rather loudly of the need to ‘save' Iraq from what he sees as Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki's efforts to monopolise political power, paving the way for a return to dictatorship. In an interview with the pan-Arab newspaper Al Hayat, given on his return to Arbil after a visit to Washington DC, Barzani said he was calling a meeting of Iraqi leaders in an effort to find "radical solutions and a specific timeframe to resolve the present crisis". If the meeting failed, he warned, "we will resort to other decisions" — a less than thinly veiled hint at secession.

The official spokesman of Iraqi Kurdistan's Ministry of Peshmerga (Kurdish armed forces), Jabbar Yawar, was more forthright: "In spite of all outstanding differences between Kurdistan and the federal government, we will not use force to solve problems. However, we are ready to cut off the hands of anyone who attacks our territory, even if it is the Iraqi army."

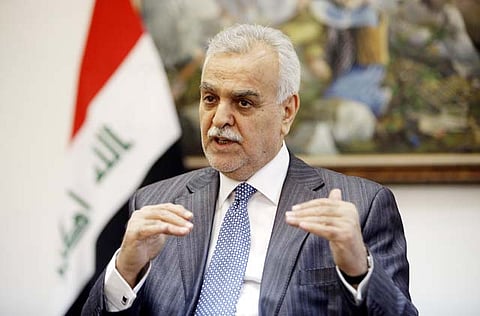

With such near war-mongering postures tensions have remained high between Iraqi Kurds and Al Maliki, a Shiite. The two biggest bones of contention remain the distribution of the nation's oil wealth and the festering bad blood over the Kurdish decision to give shelter to the fugitive Iraqi Vice-President Tareq Al Hashemi, a Sunni, accused of running a death squad. He initially went to Kurdistan after fleeing his own government's base, Baghdad, in December.

It is evident that the Kurdish problem, brutally suppressed by Saddam Hussain, will not go away easily. The Americans knew this well and forged special relations with the Kurdish leadership and these have assumed greater importance in the post-occupation period, even as Washington's influence declined in Baghdad. Al Maliki's hold on power is abetted by the rising influence of Iran in Iraqi politics.

The ‘strategic partnership' between Washington and Arbil protects the interests of both the US and the Kurds. But with the US troops no longer on the ground the Kurds have felt for the first time they are without protection directly from the US. Barzani's recent official visit to Washington as head of the government of Kurdistan was meant to address some of these fears.

The Kurdish leader urged the Americans not to allow the emergence of a ‘new dictator' in Iraq. He insisted during an interview with Al Hurra television that "even if the whole world agreed on Al Maliki, we will refuse him", while insisting that "our relationship with Iraqi Shiites will not be affected. He returned with an assurance that "the US is committed to our close and historic relationship with Kurdistan and the Kurdish people, in the context of our strategic partnership with a federal, democratic and unified Iraq."

Biggest beneficiaries

While the Kurds acknowledge that the Americans saved them from Saddam, to many observers the US action was driven less by altruism and more by commercial interests as an ‘investor' in the oil-rich province. US officials have been quoted in Foreign Policy magazine as saying the US has clear cut plans to make strategic profit-driven investments in the northern Iraqi province.

This explains the appointment of a high-ranking diplomat to head the US Consulate in Arbil. US ‘support' to Kurdistan includes intelligence training programmes for security forces, including open channels for information exchange. The Kurds have by far emerged as the biggest beneficiaries of the conflict that consumed Saddam. Washington has contributed towards developing a constitution that has diluted the powers of the central government, while being with the Kurdish region, which received 17 per cent of the annual Iraqi budget allocation or nearly $11 billion (Dh40.4 billion) in 2012. It also received additional payments, including the allocation of $560 million to fund international oil firms.

All this has not gone unnoticed. US observers have questioned the gains from this ‘special relationship' and warned that the alliance could send the wrong message in Iraq and across a region that has endured generations of Kurdish separatist struggles. The danger of igniting similar passions among the Kurdish minorities in Turkey, Iran and Syria cannot be ignored.

Nationalism and ethnic pride runs deep in the veins of the Kurds. Barzani was born on the day his party KDP was founded in 1946 in the "Kurdish Republic of Mahabad", an ill-fated attempt at secession that was brutally crushed by the Shah's army. Barzani has often said: "I was born in the shadow of Kurdish flag in Mahabad and I am ready to serve and die for the same flag." He is not going to easily forget those sentiments.

Shakir Noori is a writer based in Dubai.