Brian Sokol’s ‘The Most Important Thing’

The photographer finds out what matters to Syrians and the Sudanese the most

Imagine having to flee your home to escape the brutalities of war. Imagine having to let go of your family, loved ones and all your precious possessions. And if you did have a chance, what would be the most important thing to bring with you? Twenty-five-year-old Eman ran away from her home in Aleppo after months of conflict. At the Nizip refugee camp in Turkey where she spends her days with her son Ahmad and daughter Aishia, Eman says the most important thing she was able to bring with her was the Quran that gives her a sense of protection. For Omar [name changed], who is also from Syria, it was the buzuq. At the Domiz refugee camp in Iraqi Kurdistan the sound of Omar’s buzuq fills him with nostalgia and offers some relief from his sorrows. At the same camp, 24-year-old Aliah, blind and confined to the wheelchair, was not that fortunate enough. The most important thing she could bring with her was her soul, nothing more.

Ever since the beginning of the Syrian war, more than a million Syrians have escaped to neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Iraq or other countries in the region. The unregistered number perhaps runs into a million more. And today with little prospect of being able to safely return to their homes in the short term and the growing hardship in host countries, Syrians continue to face desperate circumstances. Most of them have had to leave their homes so suddenly or endure journeys so fraught with dangers that all they could carry with them were nothing more than keys, pieces of paper, phones and bracelets — things that looked like part of their attire or could be hidden in their pockets. Some carried with them a symbol of their religious faith, others just a memory of happier times.

American photographer Brian Sokol’s most recent project, “The Most Important Thing”, is a global portrait of refugees and the objects with which they chose to flee their homelands. Sokol, an expert in documenting human rights issues and humanitarian crises in post-conflict societies, has worked with Time, The New Yorker, UNHCR and UNICEF and is a recipient of the National Geographic Magazine’s Eddie Adams Grant. He has also been selected as one of PDN’s 30 Emerging Photographers. Now based in New York, he continues to document social issues in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. The first part of this UNHCR-sponsored project focuses on refugees fleeing Sudan for South Sudan; the second part is all about Syria. Talking about the Syrian refugee crisis, Dan McNorton, a UNHCR spokesman, says: “There has been a massive escalation of arrivals in 2013. Close to one million Syrian refugees have registered since the beginning of this year. People are fleeing without many possessions and are in need of food, sanitation and medical assistance.”

While on assignment, Sokol has been driven to tears on several occasions. In this interview with Weekend Review, he recounts his experiences and talks about why it is inspiring to see what the human heart is capable of surviving.

You have travelled from Sudan to Syria to Burkina Faso as part of this project, “The Most Important Thing”. Is there a common thread that ties these people together?

What is obvious is that everyone places their families as the highest priority.

In Syria most of the people carried simple objects such as pieces of paper, the Quran, phones and bracelets. In what way have these objects been significant to them? And how are they different from objects that people have carried with them in other conflict zones?

As for what people deem important enough to carry with them when they flee, there’s no one simple answer. Many of the Syrians I spoke with said they travelled with minimal belongings because if it became known that they were intending to flee, they could be prevented from leaving the country. As such, they crossed the border with little other than the clothes on their backs and what they’re able to conceal in pockets or the folds of their garments. Were they able to do so, they would likely travel with more, and different, objects.

This doesn’t apply to all, as some Syrian refugees manage to flee with suitcases. What’s interesting is the prioritisation of what various refugees place value upon. For the majority of the Syrians, the objects were of symbolic or religious value: a bracelet, a key, a ring, a photograph, Quran. Whereas for the Sudanese, the objects were almost all of practical or survival value: a pot, an axe, a water jug, a knife, a basket.

The journey that the Sudanese undertake is a considerably longer one, generally done on foot, and the objects that refugees value most seem to be those that help to keep them alive. Syrian refugees, in contrast, most often make the journey in a matter of hours, rather than days or weeks. The objects they most prize seemingly address their emotional or spiritual needs more than the physical.

What kind of emotions did you experience while interacting with the Syrian refugees?

Personally, I’ve been driven to tears on several occasions while working on this project — not only out of sorrow for what people have been through, but out of astonishment at just how resilient human beings are. I’ve met refugees who have seen unspeakable horrors and lost everything, and I mean family members and their sense of place — not just material objects. It’s inspiring to see what the human heart is capable of surviving.

Your photographs paint a powerful image of the struggle for survival. How did you become interested in the stories of these people?

In August of 2012 I was on assignment for UNHCR, the UN agency for refugees, and in a refugee camp for the first time. The scale of the situation — tens of thousands of people — was something that I found visually impossible to convey. Like many humanitarian crises, refugee situations tend to be reduced to statistics. For me, at least, these numbers are more or less meaningless unless and until I can somehow connect them with living, breathing people. The project is an attempt to convey the humanity of individuals who have been dehumanised by their circumstances. To show that millions of people in similar situations around the world aren’t just “refugees”, aren’t others, but are mothers and daughters — normal people with children and receding hairlines and mobile phones.

I asked them to display the single object that was of greatest importance to them for two reasons. First, it was a means to get them to tell their stories in their own words. It gave me something to dig, for that would drive the interviews forward, as well as tie the images together into a series. Second, I thought that having a written and visual record of what refugees themselves — rather than the humanitarian organisations charged with providing for them — deem to be of the greatest importance could be an effective means of targeting refugees’ needs.

Of all the objects you photographed in Syria — the ones that the families took with them when they fled their homes — which ones came across as the most significant, the most symbolic?

I can’t really say which objects were the most significant, as that varies from individual to individual. What I did notice was that among the Syrians, many of those I interviewed mentioned the Quran as being the single most important thing that they succeeded in fleeing with. Personally, the story that I was most able to identify with among the Syrian refugees I spoke to was that of 9-year-old May [name changed], and her bracelets. The image isn’t particularly special, but her story is very touching. On the night that May’s family fled Damascus, her mother set May’s beloved doll Nancy on the bed so that she wouldn’t be left behind. However, in the rush and panic that ensued, Nancy — May’s most important thing — was lost. The next best thing that made it with her to Iraq were some simple bracelets, but she still recalled in eloquent detail why Nancy, given to her on her sixth birthday by her aunt, was so precious. “She reminded me of that day, the cake I had, and how safe I felt then when my whole family was together,” she said. It seems that her story struck a chord with others as well. UNHCR recently delivered a doll donated by Mimi, a 5-year-old British girl living in Thailand who heard May’s story and cashed out her savings to get a doll for a refugee child she had never met, half a world away. Perhaps more than anything else, this has gone to show the simple humanising power that pictures and stories have in bringing people together, and generating positive actions.

What do you feel has been a source of sustenance for these people — has it been their religion, memories of their homes they left behind or these objects they carried with them?

I suppose that hope is their greatest source of sustenance among Syrian refugees. Hope of returning home one day soon. Hope of an end to the conflict, and the cessation of violence. I’m sure that religious faith and memories of home contribute greatly to that sense of hope, as does the sense of community that they find among their friends and family members who have together escaped the conflict.

Have you visited Syria? If you haven’t, would you like to go there one day to find out what became of your subjects in a conflict zone?

I haven’t been into Syria itself. All of the images of Syrian refugees were taken in the surrounding countries of Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Turkey. I would, however, love to go back and visit the families and individuals who I met while working on the project.

For more information on the project, please visit:

www.briansokol.com and www.instagram.com/briansokol

SYRIA

Omar, 37, (name changed) poses inside his tent in Domiz refugee camp, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, on November 16, 2012. Omar decided it was time to flee his home in the Syrian capital of Damascus the night that his neighbours were killed. “They came into their home, whoever they were, and savagely cut my neighbour and his two sons. They dragged the bodies into the street, where we found them in the morning.” The next day he used most of his savings to hire a truck to flee with his wife and his two sons. The most important thing that Omar was able to bring with him is the instrument he holds in this photograph. It is called a “buzuq” and he says that “playing it fills me with a sense of nostalgia and reminds me of my homeland. For a short time, it gives me some relief from my sorrows.”.

May, 8, (name changed) poses in Domiz refugee camp, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, on November 16, 2012. She and her family arrived in Domiz about a month before this photograph was taken, having fled their home in Damascus, the Syrian capital. They escaped on a bus at night, and May recalls crying for hours as they left the city behind. After travelling more than 800 kilometres, they made the final crossing into Iraq on foot. May wept again as they followed a rough trail in the cold, while her mother carried her 2-year-old baby brother. Since arriving in Domiz, she has had recurring nightmares in which her father is violently killed. She is now attending school, and says she finally feels safe. May hopes to be a photographer when she grows up. “I want to take pictures of happy children, because they are innocent, and my pictures will make them even more happy,” she says. The most important thing she was able to bring with her when she left home is the set of bracelets she wears in this photograph. “The bracelets aren’t my favourite things,” she says, “my doll Nancy is.” May’s aunt gave her the doll on her sixth birthday. “She reminded me of that day, the cake I had, and how safe I felt then when my whole family was together.” The night they fled Damascus, May’s mother put Nancy on her bed, a place where she would be seen. But in the rush that ensued, Nancy was somehow left behind, and May says these bracelets are the next-best thing to having her in Iraq.

Tamara, 20, (name changed) poses in Adiyaman refugee camp, in Turkey, on December 5, 2012. After Tamara’s home in Idlib was partially destroyed in September, the family decided their best chance of safety was to reach the Syrian-Turkish border. “When we left our house, we felt it was raining bullets,” Tamara recalled. “We were moving from one shelter to another to protect ourselves.” She adds: “We left Idlib three months ago. We spent 40 days on the Syrian side of the border with very little water and no electricity. The hygiene there was very poor. I got food poisoning and was sick for a week.” The most important thing she was able to bring with her is her diploma, which she holds in this photograph. With it she will be able to continue her education in Turkey. Through a generous education programme, the government will allow qualified Syrian refugees to attend Turkish universities beginning in the March semester. Ramazan Kurkud, head of education programmes at Adiyaman, said 70 BA candidates and 10 MA candidates from the camp have so far submitted applications to study at Turkish universities.

Laila, 9, (name changed) poses in the place where she and her family are taking shelter in Erbil, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, on November 17, 2012. Together with her four sisters, mother, father and grandmother, Laila arrived in Erbil five days before this photograph was taken, after fleeing their home in Deir Alzur, Syria. Her family is one of four living in an uninsulated, partially-constructed home; there are about 30 people sharing the cold, draughty space. Laila recalls explosions all around them for days, but the family finally decided to leave Deir Alzur when their neighbours’ house was hit, killing everyone inside. The most terrifying thing about the months before they fled, she says, “was the voice of the tanks. It was even more scary than the sound of planes, because I felt like the tanks were coming for me.” In the background throughout the interview with Laila, a television channel from Deir Alzur displayed images of incredibly graphic violence and destruction. When asked what she feels when seeing those images again and again, she replied, “Watching TV makes me remember Syria and what I saw there. It makes me feel sorry and sad in my heart — but I want to keep it on.” The most important thing Laila was able to bring with her are the jeans she holds in this photograph. “I went shopping with my parents one day and looked for hours without finding anything I liked. But when I saw these, I knew instantly that these were perfect because they have a flower on them, and I love flowers.” She has only worn the jeans three times, all in Syria — twice to wedding parties, and once when she went to visit her grandfather. She says she won’t wear them again until she attends another wedding, and she hopes that, too, will be in Syria.

SOUTH SUDAN

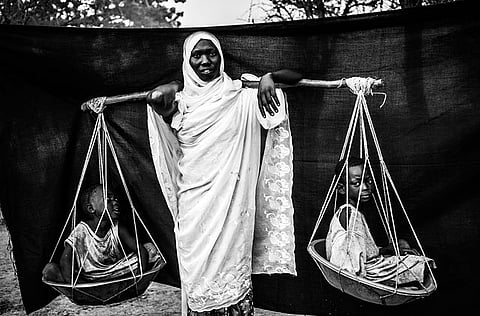

Dowla Barik, 22, poses in Doro refugee camp, Maban County, South Sudan, on August 5, 2012. Several months earlier, Dowla and her six children fled their village of Gabanit in Sudan’s Blue Nile state after numerous bombing raids. The most important object that Dowla was able to bring with her is the wooden pole balanced over her shoulder, with which she carried her six children during the ten-day journey from Gabanit to South Sudan. At times, the children were too tired to walk, forcing her to carry two on either side.

Noora, who doesn’t know her age, stands inside her makeshift shelter in Doro refugee camp, Maban County, South Sudan, on August 5, 2012. A month earlier, Noora and her three children fled the fighting in their home village of Mayak in Sudan’s Blue Nile state that killed her husband. The most important object that she was able to bring with her is the wooden basket that he holds, as it allowed her to carry her 1-year-old son, Sabit Idris, atop her head during their four-day journey to South Sudan. Meanwhile, Noora’s 2-year-old daughter Hanan and 3-year-old son Nguma made the journey on foot. The children are now malnourished, and Noora has to leave them for much of each day to earn money by fetching and selling water to better-off refugees.

Taiba Yousuf, 15, poses in Jamam refugee camp in Maban County, South Sudan, on August 12, 2012. Eight months before this photograph was taken, Yousuf fled her village of Lahmar in Sudan’s Blue Nile state. Leaving with nothing but the ragged clothing she was wearing, she, her mother and five brothers embarked on a two-month journey to South Sudan. She regularly went for days at a time without eating, wore no shoes, and did not even have a cup or a plastic bottle to carry water. She stayed alive by scavenging for fruits in the forest, and by begging for food and water from other refugees and in villages she passed through. During the journey she suffered from diarrhoea, and a skin infection which made walking painful. Unlike the other people pictured in this series of photographs, Yousuf holds no object, as she made her journey from Blue Nile empty-handed. Disabled by tetanus, which took her left arm four years ago, Yousuf is among the most vulnerable people seeking refuge in Maban County. While she no longer lives in fear, she says that she still doesn’t have enough to eat.

Seventy-five year old Shari Jokulu, who is blind, poses with her son Osman Thawk, 40, in Jamam refugee camp, in Maban County, South Sudan, on August 8, 2012. In September 2011 war came to their home in Bau County, in Sudan’s Blue Nile state. For five months Shari and Osman went from village to village, looking for a safe place. At times, Shari grew so hungry that she ate the leaves of the lalof tree. Some of the friends and neighbours who accompanied them died of illness or hunger on the way. Still, the conflict followed them everywhere they went, and in February 2012, they arrived in Jamam. The most important thing that Shari was able to bring with her is the stick that she holds in this photograph. “I’ve had this stick since I went blind six years ago,” she says. “My son led me along the road with it. Without it, and him, I would be dead now.”