Vacheron Constantin unveils La Quête du Temps: When Watchmaking becomes cosmic art

Astronomical clock debuts at Louvre's art exhibition

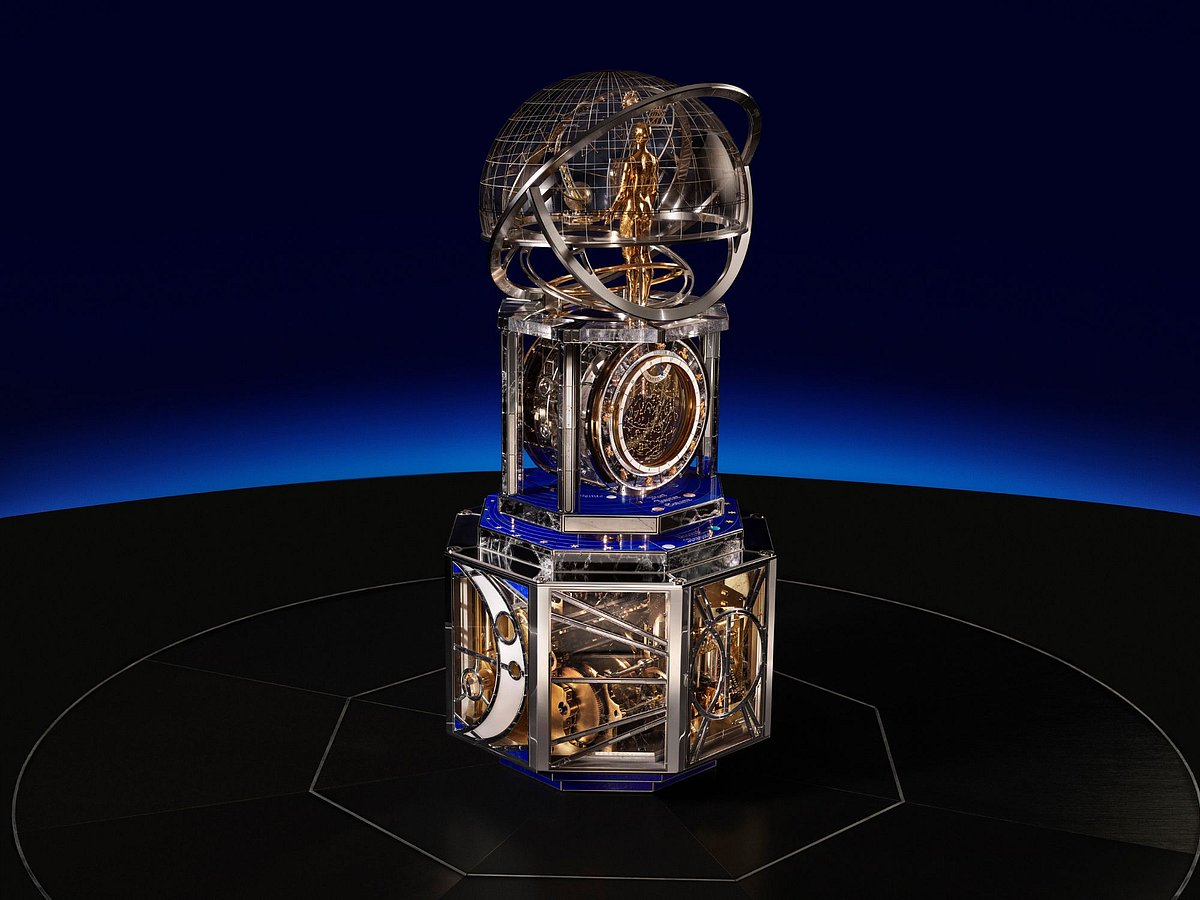

What does time look like when it’s no longer just measured, but sculpted, sung, and set into motion? Vacheron Constantin has an answer, and it doesn’t come in a discreet wristwatch box. It towers over a meter high, contains 6,293 mechanical components, and pulses with music, light, and choreography. Its name: La Quête du Temps.

Seven years in the making, this astronomical clock is less an object than a manifesto - a mechanical cathedral that fuses horology, art, and automaton theatre. When it debuts this fall at the Louvre’s “Mécaniques d’Art” exhibition, it will not merely mark Vacheron Constantin’s 270th anniversary. It will reframe what it means for a watchmaker to “keep time.”

The Astronomer who dances with the universe

At the heart of La Quête du Temps is not a tourbillon or a dial, but a figure - an Astronomer automaton who comes alive in a 90-second ballet of gestures. He points to the phases of the moon, traces the stars, and even indicates the hours and minutes on scales suspended beneath a crystal dome. Each movement is precise, silent, and achingly human. Each performance, unique.

This isn’t animation as embellishment. The automaton is integrated into the timekeeping itself - a horological complication in motion. Behind its natural grace lies a staggering 158 cams and 144 programmed gestures, choreographed like mechanical poetry. To underscore the drama, the Astronomer’s movements are accompanied by specially composed melodies from Woodkid, played not digitally, but via a custom-built mechanical music machine.

A monument to ingenuity

Structurally, the clock unfolds in three acts. The celestial dome - painted by hand from the inside in a feat of miniature artistry - captures the constellations as they appeared above Geneva the very morning Jean-Marc Vacheron signed his first apprenticeship contract in 1755. Beneath it, an astronomical clock loaded with 23 complications, from a perpetual calendar to a 110-year precision moon phase, anchored by a massive tourbillon with Vacheron’s signature Maltese Cross cage. And finally, the base: a lapis lazuli solar system where planets orbit in cabochons of hard stone, from azurite Earth to jasper Mars.

Every inch of this mechanical monolith has been touched by a craftsman’s hand. Diamond-set bezels glitter around the dials. Rock crystal panels open the clock’s heart to light. Guillochage, grand feu enamel, marquetry, engraving, sculpture - it’s a Geneva-style Renaissance workshop reborn.

Patents, partnerships, and the pursuit of more

La Quête du Temps isn’t just beautiful. It’s also an engine of innovation. Fifteen patents have been filed for its watchmaking and automaton mechanisms, covering everything from coaxial power-reserve indicators to a mechanical memory that drives the Astronomer’s time display.

The project united not just Vacheron Constantin’s ateliers, but outside luminaries: François Junod, the world’s greatest automatier; the horological artisans of L’Épée 1839; astronomers from the Geneva Observatory. The result feels less like a product launch and more like a symphony of disciplines, tuned to the rhythm of the cosmos.

From monument to wrist

But Vacheron Constantin didn’t stop at the Louvre. From this monumental clock comes a wrist-bound echo: the Métiers d’Art Tribute to The Quest of Time, a double-sided timepiece limited to just 20 examples. It houses the new Calibre 3670, a 512-component manual-wind movement with four patents of its own. One dial features a human figure whose arms mark the hours and minutes in a double-retrograde display, set against the constellations as they appeared in 1755. Flip it, and a sky chart tracks the stars in real time.

It’s a distillation of La Quête du Temps’s grandeur into wearable form — still wildly complex, but undeniably intimate.

Time as cultural statement

“Is it always possible to be amazed? Undeniably,” says Laurent Perves, CEO of Vacheron Constantin. The amazement here doesn’t just come from the technical audacity, but from the cultural gesture. By situating La Quête du Temps at the Louvre, the Maison isn’t merely presenting a clock. It’s claiming space alongside centuries of human ingenuity, from Egyptian water clocks to Enlightenment marvels.

The message is clear: horology at its peak isn’t just about telling time. It’s about telling a story of time itself - how we’ve measured it, imagined it, and been humbled by it.

And in La Quête du Temps, that story now dances, sings, and shines under a crystal dome.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.