Trap: Your guide to rap genre that’s gone mainstream

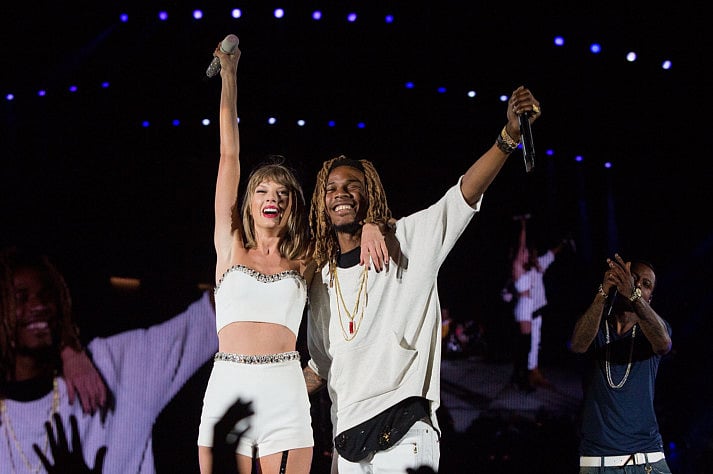

It’s gone mainstream, with Taylor Swift and Kate Hudson dancing to Fetty Wap, but it has its roots in Atlanta’s segregated past

You used to want to stay away from the trap: an abandoned house where drugs are peddled. As OutKast’s Big Boi explained on 1998’s SpottieOttieDopalicious, it was the absolute last resort for employment. A decade later, though, those trapped in the early noughties drug trade spoke up for themselves. It was initially sold as a southern revival of west coast gangsta rap (they initially invited comparisons to NWA), but according to these rappers, their music was the byproduct of their (and OutKast’s) native Atlanta being a crack-cocaine town, a lasting result of the Reagan-era “war on drugs”.

Little did they know that trap would have a lasting influence itself. The stories were alluring, bellicose and, perhaps most importantly, different from the triumphant tales of excess coming from New York and Los Angeles in the early noughties. The sound’s dramatic synthesized production would eventually cross over to EDM and even pop, though not without controversy. It evolved from an Atlanta street-level movement to a global phenomenon, but it has its roots in the south’s segregated past.

In 2005, with help from play at Atlanta strip clubs and nightclub airplay, Jeezy became its first superstar: his Def Jam debut album Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101 went platinum in its first month. Jeezy, Gucci Mane and TI — all black men in America, and the holy trinity of trap — were often asked if their music glorified what gangsta rap seemed to before. “I don’t rob or sell dope, I don’t do anything illegal anymore,” TI told Ozone in 2004. “But if I had to choose between selling dope or my children starving, guess what I’m going to be doing? It’s not realistic to expect someone to make that choice.”

The type of projects Jeezy and TI were rapping about featured on shows such as The Wire and most notably True Detective, during the one-shot scene in season one where Matthew McConaughey’s Rust Cohle drags a suspect through a housing project.

Gucci Mane would release The State Vs Radric Davis, one of his most commercially successful albums. TI and Jeezy were appearing at the BET awards. Soon the subgenre’s production crossed over to EDM and pop, while being stripped of its sociopolitical context. Now, there may be just a few constants in what is considered trap production: an 808 heartbeat, bass, and rapid-fire cascading percussion fills.

In 2011, however, Waka Flocka Flame’s Hard in Da Paint introduced listeners to Lex Luger. His beats in those songs are grandiose, as also heard in Jay Z and Kanye West’s H.A.M. with its urgent strings and operatic voices. So began trap’s gilded age. Producers sampled lyrics and borrowed references about crack houses and the crime that surrounds them, not to mention the name itself. It also resulted in one-off Cake, where a dead-eyed Lady Gaga raps and a disembodied male voice, likely producer DJ Shadow’s, says: “I’m posted in the trap, strapped with the AK.” This was glib trap appropriation.

But this was also only the start of how trap would get out of the hands from those who still associated the word with “crack house”. Trap was a style now; Katy Perry’s 2014 single featuring Juicy J, Dark Horse, was labelled as such. In 2012, two new trap rap stars emerged. 2 Chainz became Def Jam’s hottest new signee not for his depictions of drug dealing, but for punchlines that land like dad jokes. Meanwhile, Future’s transition from old moniker Meathead was cemented not with his signing to Epic, but with songs where he sounded like an Auto-Tuned drunkard. Once they became major-label commodities, even weirder upstarts arrived — the bluesy Rich Homie Quan, trap mathematicians Migos and rap game Flubber Young Thug.

Often these rappers use trap tropes as means by which to toy with flow, cadence and actual singing. These experiments caught on, the biggest success being when Drake gave his best Migos imitation in his Versace remix, launching countless others. “I don’t know who created it, if it was Future or Migos, but all them n***** sound the same,” Snoop Dogg said on his talk show GGN, before he pantomimes the trio’s wheezy triple-time flow. Lately, however, such ubiquity hasn’t translated to platinum sales for trap rap’s original superstars.

So where does trap head next? There is Sweden’s Yung Lean, who borrows from US cultural references like Gucci Mane’s off-kilter flow for kicks, it seems. There is also a burgeoning trap rap movement in Russia. The big three still matter, just not as much as before: TI is a mainstream star, though one of his two more recent hits relied on Young Thug’s starpower; Gucci Mane is more of a cult favourite now, with his endless stream of free mixtapes; Jeezy’s most beloved album is still his first.

The latest trap song to hit it big, Fetty Wap’s Trap Queen, sounds nothing like what anyone else had done. As Taylor Swift knows, the main source of its appeal hasn’t been its setting, but its exuberance (“I’m like hey, what’s up, hello”). On August 8, the 1989 superstar brought the Paterson, New Jersey, rapper out to do Trap Queen together, which meant she actually had to sing “I be in the kitchen cooking pies with my baby, yaah.” If Swift thought for even just a second of how lucky she is not to know what that’s like, then trap has done its job.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.