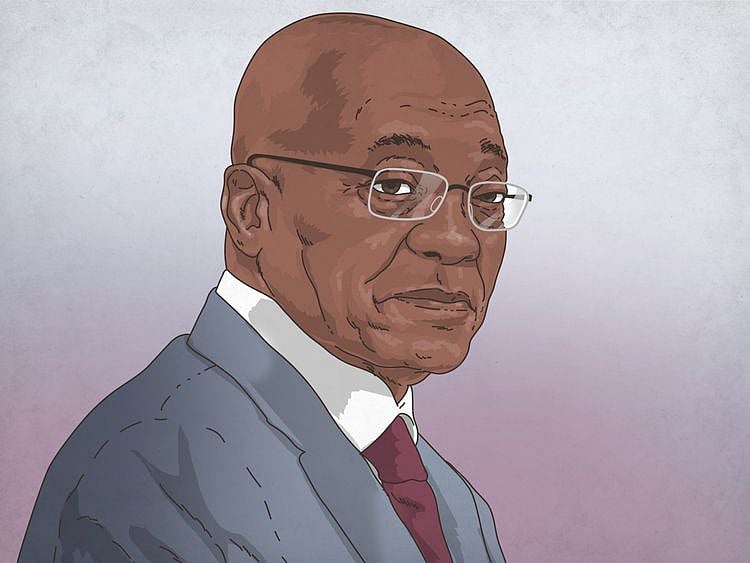

Newsmaker: Jacob Zuma — Casting a dark shadow in South Africa

Legal travails of former president have sparked worst spasm of violence since apartheid

For the past week, images emerging from South Africa are a painful reminder of the tumultuous and tortuous times that brought an end to apartheid.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this in the Rainbow Nation, a land that seemed so full of hope and promise yet has struggled since then to fully realise its potential. And while the African National Congress, its leaders who campaigned so long and hard for justice and equality, emerged victorious then, it seems as if the decades since 1994 have been lost. Or stolen.

Where there was courage, corruption followed. And central to this unfulfilled potential has been the dominant figure of Jacob Zuma, the former president and one who it seems now has a face off with law — even if those post-Apartheid laws were meant for all, just not for him.

The death toll from this past week is close to a hundred, scores more injured and thousands of businesses forced to close as street violence across South Africa followed the jailing on July 7 of the 79-year-old for contempt for refusing to appear before a special judicial commission investigating numerous corruption scandals during his nine-year presidency that ended in 2018.

Zuma has challenged his sentence on the grounds of his alleged frail health and risk of catching COVID-19.

Zuma supporters, who believe he is the victim of a political witch-hunt, burnt tyres and blocked roads in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal. As the nation’s first Zulu president, he is widely popular and holds considerable sway in the nation’s largest ethnic group. For most others, he is viewed as a political leader whose time in power was a period for pocket-lining and accentuating the woes faced by the nation as it struggled to come to terms with the reality of building a new nation from the ruins of decades of international isolation and apartheid.

The rise of Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma, who was born April 12, 1942, in Nkandla, received no formal schooling. He joined the ANC in 1959 and its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) in 1962. Within a year he was jailed for attempting to overthrow the whites-only regime and sent to jail on Robben Island, the crucible of the freedom movement with Nelson Mandela and a coterie of ANC leaders who would go one to free South Africa. After his release, he set up underground networks for the military wing, forced into exile in Swaziland and Mozambique — credentials shared by most of the senior ANC echelon. He moved on to Lusaka, Zambia, controlling the underground structures and heading its intelligence network — giving him an unparalleled knowledge in who did what, who owes whom and where skeletons are figuratively and literally buried.

When the South African government’s ban on the ANC was lifted in 1990, Zuma returned to the country and was elected chairperson of the southern Natal region. He became the ANC deputy general secretary in 1991 — again using the information as a valuable tool for his political advancement.

In December 1997 he was elected deputy president of the ANC, and in June 1999 he was appointed deputy president of the country by President Thabo Mbeki. Zuma was widely expected to eventually succeed Mbeki as president of the ANC and as president of the country. In June 2005, however, Mbeki dismissed him after a fraud conviction for one of his close associates.

It’s a stench of graft that has lingered.

The hardship that persists 27 years after the end of apartheid is a major reason why hundreds of shops and dozens of malls have been stripped bare in a nation where roughly half of the country’s 35 million adults live below the poverty line and that young people are disproportionately affected by unemployment.

As South Africa’s malaise has deepened, so too Zuma’s resolve not to engage with justice authorities as they sought answers to a litany of scandals that festered under his leadership.

Allegations and denials

South Africa’s main anticorruption watchdog published a report in 2016 alleging that Zuma’s friends, the Gupta brothers, had tried to influence the appointment of cabinet ministers and were unlawfully awarded state tenders. As the investigation picked up momentum in 2018, the Guptas left South Africa. They deny any wrongdoing.

Zuma also faces legal woes over corruption and fraud relating to a Dh7.3 billion arms deal from the 1990s when he was deputy president. The charges were set aside in 2009, paving the way for Zuma to run for president, but were reinstated in 2018. He denies wrongdoing.

In December 2015, Zuma fired finance minister Nhlanhla Nene replacing him with unknown parliamentary backbencher Des van Rooyen. Zuma was forced to sack van Rooyen and reappoint a previous finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, four days later after the rand collapsed. President Cyril Ramaphosa reappointed Nene in February 2018. Later that year, Nene told a judicial corruption inquiry he was fired by Zuma for refusing to approve a multi-billion dollar nuclear power deal with Russia in 2015.

Even Gorghan’s firing is shrouded in controversy. He and his deputy, Mcebisi Jonas, were canned in a midnight reshuffle in March 2017. The next morning, markets plummeted, and senior ANC officials fumed that they knew nothing or were not consulted about the firings.

Those Gupta brothers? Zuma let them use the top-security Waterkloof airbase to fly in 200 guests from India for a family member’s wedding in 2013, sparking a public outcry.

And then there’s the upgrades to Zuma’s property portfolio. Soon after becoming president, it emerged that millions of dollars of public money had been spent on upgrades to Zuma’s sprawling country estate, including a swimming pool that one minister justified as a firefighting resource.

There is also the matter of an alleged assault against Fezekile “Khwezi” Kuzwayo, the HIV-positive daughter of his friend who had been imprisoned on Robben Island with Zuma during the apartheid era. Zuma denied the allegations and was acquitted.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.