EU leaders endorse China accord at tricky time for ties

Now is the time to intensify cooperation and help define international relations

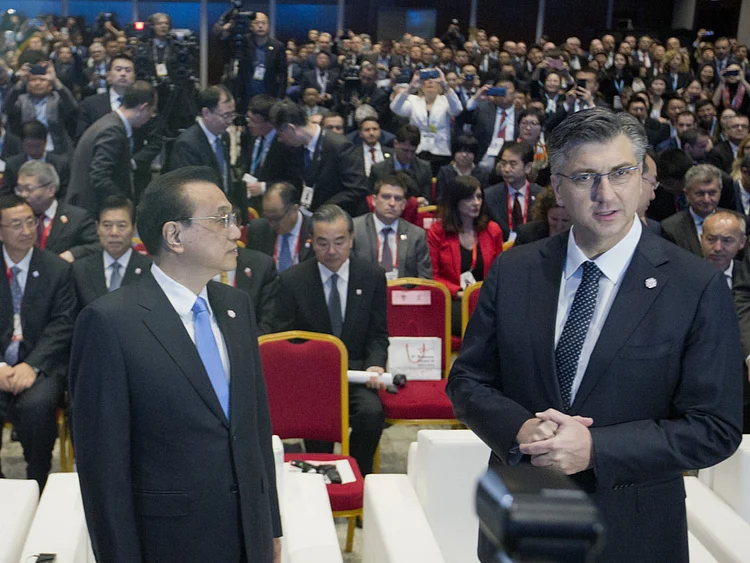

China co-hosted the annual 16+1 meeting on Friday with key governments in central and Eastern Europe. This latest event underlines how Europe is becoming increasingly important for Chinese foreign policy, fuelling concerns in Brussels that Beijing is ‘dividing and ruling’ to undermine the continent’s collective interests.

Take the example of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s trip last month to Italy where he signed a landmark Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the Belt and Road (BRI) initiative. Brussels has long had reservations about BRI, not least given frustrations over Beijing’s perceived slowness to open up its own economy, and a wave of Chinese takeovers of European firms in key industries. Italy’s decision is only the latest one which has underlined Beijing’s growing influence across the continent, which EU officials are increasingly conscious of. Another example is the ‘16+1’ initiative, held in Croatia on Friday, aimed at intensifying and expanding cooperation in the fields of investment, transport, finance, science, education, and culture with 11 EU member states and five Balkan countries.

Key trends are increasingly apparent in China’s external interventions in Europe. For instance, it is becoming increasingly clear that Beijing is tailoring its approach around the bespoke needs of individual states or blocs of countries — such as 16+1. Further, Chinese overtures to Europe are coming with a clear quid pro quo as underlined by Italy’s signing up to BRI in exchange for Beijing’s investment. In this context of bilateral angst, the EU also met last week with China for its own annual summit in Brussels. The two sides, led by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, reached an unexpected joint statement on Tuesday that saw significant 11th-hour compromises from Beijing in an attempted show of bilateral unity.

Key measures agreed include a commitment from China to address EU concerns over state subsidies to businesses creating unfair global competition, plus the promise of key measures soon to liberalise its market to try to reach a bilateral investment agreement by 2020. Beijing also agreed to a dialogue around reforming the World Trade Organisation which is an EU priority. The multi-page joint statement, reached after last-ditch negotiations since the start of April, was by no means assured. In this sense, Tuesday’s summit was used as an opportunity for both sides to stress multiple areas of common interest and cooperation, especially at a time when both have major tensions with the Trump administration.

Here the EU co-hosts, Juncker and European Council President Donald Tusk, alongside Li Keqiang, stressed a range of issues — from the importance of an open, multilateral international order, to tackling climate change. Global warming, for instance, is a topic where there has long been a fruitful bilateral dialogue.

Under the terms of the 2015 EU-China climate change declaration, which was re-affirmed on Tuesday, both parties cooperate on developing a cost-effective low carbon economy. This is especially important in light of the Trump team’s abdication of the climate agenda.

Collectively, the EU and China account for around one third of global greenhouse emissions — which grows to one half when the United States is added into the picture. And the 2015 bilateral climate change declaration was one of the key drivers, along with the Obama administration’s diplomacy, of the Paris deal. The reason why EU-China discussions on climate change are so generally cooperative is that, fundamentally, both share a vision of a prosperous, energy-secure future in a stable climate and recognise the need for bilateral collaboration to realise this agenda. Their 2015 agreement, for instance, agreed to intensify cooperation in domestic mitigation policies, carbon markets, low-carbon cities, greenhouse gas emissions from the aviation and maritime industries, and hydrofluorocarbons.

China’s planned investment in the green economy is huge, a fact that the EU is increasingly recognising. This investment is buttressed by Beijing’s policy commitments on the climate, clean air and energy agendas. In recent Five-Year Plans, for instance, a strategic direction has been set for the economy with determination to change the country’s development model from low-grade labour-intensive manufacturing towards a greater emphasis on services and innovation.Another signal of the seriousness of Beijing’s climate ambitions is the fact that it is using the experience of its sub-national pilot trading schemes to inform development of its future national model. Here, Beijing is proving open and willing to learn from the pioneering European Emissions Trading System, while adapting this experience to China’s domestic circumstances.

To be clear, there is still a way to go before China has a full-fledged carbon market, and both parties have yet to develop new low carbon standards in key industrial sectors. However, the direction of travel is clear: cooperation could build low carbon industries in a range of sectors, and also align Europe more closely to the world’s future largest economy. Taken overall, despite lingering tensions over issues such as BRI, it is clear that the EU and China have much to potentially gain from a deeper partnership on issues from international trade to climate change. Yet the window of opportunity to collaborate may not remain open indefinitely. Now is thus the time to intensify cooperation to bolster growth, and help define the landscape of international relations in the 21st century alongside the United States.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.