Landslides in politics are not exactly rare in modern Anglo-American politics: Lyndon Johnson had one in 1964, Richard Nixon had his in 1972, and Ronald Reagan had two of them, in 1980 and 1984.

They are less frequent in Britain’s parliamentary system, with two standing out: Margaret Thatcher’s stunning 1983 victory giving the Conservatives a majority of 144 and Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ earthquake of 1997 resulting in his party having 179 more seats than the Conservatives.

A second category of notable democratic events are “shockers”. We are well acquainted with Donald Trump’s 2016 stunner. Indeed, if journalism had a concussion protocol like the National Football League, most media pundits and certainly all of the #NeverTrump Republicans would still be in the blue tents, muttering vaguely about not having seen it coming.

Which leaves us wondering how to classify Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s stunning triumph. His new 80-seat majority in the House of Commons, while not quite as large as Thatcher’s or Blair’s zeniths, is nevertheless enormous when measured against the narrow margins of a country whose politics have been deadlocked for a decade.

And for a variety of reasons, almost no one saw it coming, despite some polling that suggested a Tory majority of more than 20. Somehow the toxic brew of Twitter, elite British media, and the eye-catching antics of large crowds and extravagant gestures combined into the British version of the Manhattan-Beltway bubble of 2016 to leave so many professional pundits agape.

Deeply divided

I had hoped for a Johnson win but didn’t think this scale of victory was possible. Johnson’s Tories can fashion themselves along Benjamin Disraeli’s Tories of 150 years ago, seeking growth and opportunity for the common citizen but embracing brilliance and excellence in any sort of achievement.

And now political horizons are open to the British that can prove decisive for the West. Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote of Disraeli, “In 1878 at the Congress of Berlin, he emerged as the dominant figure and combatant.

By being bold and persistent, threatening to break up the congress and even declare war on Russia, he succeeded in reversing Russia’s gains and resolving the crisis in favour of Britain and Europe.” Himmelfarb noted that “perhaps [Disraeli’s] greatest tribute came from the prime minister of Prussia. It was affectionately and admiringly — not cynically or derisively, as one might suspect — that Otto von Bismarck hailed him: ‘Der alte Jude, das ist der Mann.’ “(The old Jew, he is the man.)

The free world hopes Johnson is as successful in dealing with the Chinese and the Russians as Disraeli was with the Russians and the Germans of his day. Johnson does not have the vast British fleet of yore, though he should certainly fulfil his pledge to begin its urgently needed expansion.

What Johnson can most certainly deliver, though, is leadership in crafting solutions to the modern “two nations” dilemma burdening the West: Vast wealth has accumulated at the intersection of technology and need, resulting in dazzling innovations in many places but despair, often accompanied by addiction, in many others.

As this crisis of declining opportunity has grown, our politics have become as deeply divided as any time since the Vietnam War, and the organs of media are essentially poisoned on left and right with a sort of ferocity that frequently blinds each to the other’s point of view and actual, genuine virtues.

There is still hope

Yet there is hope that politics can become joyful again. That is especially hard for the most vocal people on both sides of the American chasm spitting invective at their opposites, about the character of Trump and his supporters or the absurdity of the threadbare rushed and doomed articles of impeachment. But there is still hope.

It can be glimpsed in Johnson’s ebullient win and on Trump’s best days. Decisive figures such as Trump and Johnson can marry their decisiveness and energy to domestic and international innovation and create landslides, despite fierce opprobrium at home. All it takes is a very tough skin and a gambler’s faith in luck. Each needs to continually work to stay on his positive game, resisting his punitive urges.

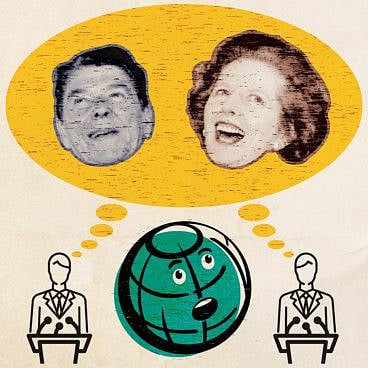

They will do so if they want more than immediate victories. Thatcher and Reagan were not hailed as the heroes in their day that many consider them now. Johnson and Trump could not be more temperamentally different than their predecessors.

Together, perhaps, they can reach and enforce an understanding with China and spread opportunity throughout their entire counties. Check back in 30 years. We will know then if there emerged a partnership for the ages out of this pair of shocking wins, and perhaps even a landslide or two.

— Washington Post

Hugh Hewitt is a noted American radio talk show host. He is an academic and author who specialises in law, society and politics.

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.