Mobeen Ansari, award-winning photojournalist, puts diversity in focus

Pakistani photographer, author, artist and documentary maker refuses to allow his aural condition to get the better of him, instead turning it to his advantage

Mobeen Ansari and his father were atop the 4,693m Khunjerab Pass on the borders of Pakistan and China. Both photography enthusiasts, they were savouring the scenic splendours of the Karakoram Mountain range — one of the most spectacular areas in the world.

‘It was freezing,’ recalls Mobeen, an award-winning Pakistani photojournalist. ‘And the winds were strong.’ But nothing could stop the duo from fishing out their cameras and start capturing on film the picture-postcard beauty of the region.

However, even as he was clicking away, Mobeen noticed that his father was shooting the landscape moving clockwise pivoting on his heels. ‘I found that strange,’ he says.

Mobeen, who was barely 12 at the time, would realise a week later the reason his father, an IT engineer and a shutterbug, opted to shoot in that style. ‘Back home, he printed the pictures he’d clicked and carefully taped them in sequence... to create a panoramic photograph of the spectacular scene,’ says the now 32-year-old, in an email interview from Lahore.

Although the incident happened some 20 years ago, to this day Mobeen is still in ‘awe of that photo, and the power of what photography can do’.

In the UAE from September 17 for a series of exhibitions of his works and to speak at a variety of forums in Sharjah, Dubai and Abu Dhabi, Mobeen says a passion for photography developed in him from the time he was a kid.

Using a digital Kodak camera his father gifted him, which he would take along religiously to school every day, he documented portraits of ‘teachers, friends, janitors, volleyball matches, my friends being late to school, getting caught by the prefect, guys fighting over a girl…’

[He's a photographer, poet and teacher: this blind man hasn’t lost sight of a full life]

Appreciative of his skills, the principal named Mobeen ‘Pictorial Historian’. ‘The award became a vital stepping stone in my journey to photojournalism,’ he says.

The journey, though, was not an easy one.

Hearing impaired

Afflicted with meningitis when he was barely a few weeks old, Mobeen’s senses of hearing and balance were severely affected. Growing up, he struggled to hold conversations, having to listen carefully to the speaker, watching their lips closely and ‘often asking them to repeat’. But the optimist quickly discovered the silver lining to the cloud; not being able to hear well, he says, heightened his senses of touch and sight, encouraging him to develop a passion for the arts including sculpting, drawing and painting.

‘My parents always told me ‘when God takes away something from you, He gives you something else’. They made sure I would never see [my condition] as a disability but as a superpower,’ says the fine arts graduate who majored in painting from Rawalpindi’s National College of Arts.

‘When you are not able to hear, you emphasise on the effort to see. For example, when I’m driving, I have a much greater visual concentration to look at blind corners, rear and side view mirrors to make sure I don’t miss anything. I apply the same principle to photography and art – keep an eye out for every detail.’

Being aurally challenged also means Mobeen has to depend a lot on body language to decipher what the speaker is saying. But that has not stopped him from fine-tuning his condition to make it work for him. ‘[Not being able to hear] makes me understand people in silence better than when they are verbal. This especially works wonders when I do portraits,’ he says, perhaps also helping make his photography ‘universally understandable’.

One of his first portraits that earned him praise was taken while Mobeen was still in school. Freezing the anguish of a schoolmate sobbing on a basketball court following a squabble with friends, Mobeen soon began perfecting the art of ‘capturing human emotions spontaneously’ – a quality that sets this photographer’s work apart from several others of his ilk.

Portraying diversity

Growing up in Rawalpindi, Mobeen stresses that his milieu was multicultural. With icons of different faiths dotting the landscape of the city, the photographer was keen to highlight the diversity he saw all around him. ‘Look out over the city, and you will find a mandir, gurudwara, church… even a synagogue all within a one-mile radius,’ he says, adding it was inspiring to live ‘in such close proximity to these structures and diversity’.

To celebrate that, he began work on White in the Flag which he published in 2017 to coincide with Pakistan’s 70th birthday. (This was his second book. The first, Dharkan: The heartbeat of a Nation, features portraits and stories of iconic people and unsung heroes of his country.)

Using more than 100 pictures to portray diversity, White…, which was close to eight years in the making, reflects the shrines, festivities, traditions and rituals of minority communities in Pakistan including Hindus, Sikhs, the Kalash tribes, Parsis and the Bahais.

Art in his genes

‘Photography helped me become a better artist and art helped me become a better photographer,’ says Mobeen, who perhaps has the genes of photography in him – like his father, his grandparents too were accomplished photographers. ‘They documented their life, family, as well as historical events such as the partition through their lens. Seeing moments in time frozen like that always fascinated me.’

Mobeen credits his grandmother for playing a role in shaping his perspective regarding diversity. ‘Her only best friend in life was a Parsi woman named Rubyna Colombowalla,’ he says. But following the partition in 1947, his grandmother migrated to Pakistan while Rubyna stayed back in Jabalpur, a city in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. ‘Nevertheless, grandma would always remember her fondly and used to tell me about the many Parsi festivities she participated in.’

Diversity is evident in Mobeen’s immediate family as well. ‘My father’s best friend was a Christian and they grew up together since they were in Grade 4. I myself grew up going to Easter services and Christmas parties,’ says the author.

‘As a Pakistani photographer, I wanted to show and celebrate pluralism and tolerance through my images.’

Mobeen speaks from experience, relating an incident when one time he set off to photograph a Buddhist community in a village in interior Sindh. ‘It took us nearly eight hours of driving to reach there,’ he says. Shoot over, they were preparing to return when a local villager insisted that they spend the night there as it was too late to drive back. ‘The inhabitants of that village were Hindu, and one of my colleagues was a Christian, and under the night sky, we talked about religion and faith; it was the most enlightening discourse I’d ever had,’ says the lensman.

‘At dawn the next day, one of the Buddhists came by and said to me Tareeqa alag, Zubaan alag, baat Aik (different methods, different language, but same message).’ Clearly, words that held an ocean of meaning.

Another time Mobeen was photographing Baisakhi – the spring festival of Sikhs – at Panja Sahib Gurudwara in Pakistan. An important pilgrimage spot for the Sikhs, the 16th-century shrine also has a giant rock said to bear the handprint of Guru Nanak Dev, the founder of Sikhism. To get there, devotees have to wade through a shallow pond before climbing a flight of slippery marble stairs.

‘An elderly man from India wanted to touch the handprint but was struggling to climb up the wet marble stairs. Seeing him, two local officials quickly slipped off their shoes, stepped into the pond and gently helped him to the [revered spot]. They waited until he finished praying before bringing him back safely to high ground. The man’s wife could not thank the officials enough, calling them her own sons,’ recalls Mobeen. ‘It’s remarkable to witness such instances where humanity prevails.’

A photograph of the shrine would go on to become the last picture in White...

For Mobeen, experiences clearly speak louder than words, helping underscore his belief in humanity. He mentions how once while shooting a Holi celebration up close – where coloured powders and liquids are splashed on celebrants – he found himself covered with colour, which just wouldn’t wash off. Later, back home, his aunt suggested using turpentine to be rubbed on the coloured areas to remove it, but ‘that only left my skin smarting’, he says.

‘Later that night, I was dining with a Parsi family and when they saw the pigments on my face and hands, they gave me a special soap to wash it off.’ It worked and the dyes disappeared, but what remained to colour Mobeen’s memories was the beauty in diversity.

‘This whole transition from celebration to cleansing between two different religious communities was a beautiful way to celebrate religious diversity,’ says Mobeen, who has spoken at several workshops and seminars on photography across the world and has exhibited his works in the US, Italy, Iraq and China.

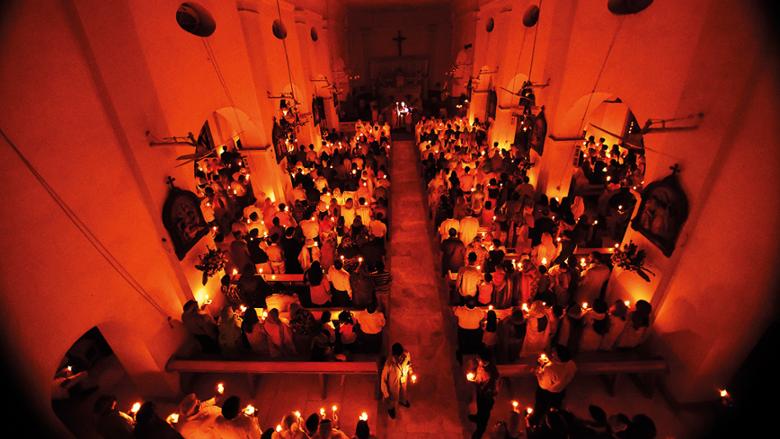

For Mobeen, the experiences while photographing the many different religious places of worship have been serene, eye opening and mind-expanding. ‘Listening to the hymns on the Easter vigil amidst a sea of candles in a cathedral, partaking in Seva (selfless devotion in Sikhism) in gurudwaras, seeing the commonalities in the respectful offerings to the sea in Zoroastrianism and Hinduism… all taught me more about my faith and to find beauty in it, which I wouldn’t have seen otherwise. [The experiences] taught me that we all are humans, and we all are connected by humanity and spirituality, no matter what our faith, caste or creed.’

Travels across the country

From capturing Holi and Diwali festivities in the shrines of Tharparkar in Sindh to the celebrations of the Kalash tribe in the Chitral district of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, Mobeen has also travelled across the country documenting cultures of minorities for White…, a book that has been endorsed by Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan.

What does the title signify? ‘The green in the Pakistan flag represents Muslims, while the white is a representation of the minorities. I called my book White in the Flag to emphasise that fact,’ he says.

Street photography

Even a casual perusal of his portraits would reveal the streak of street photography evident in them, highlighting the fact that he is clearly a people’s person. ‘Street photography is almost always impossible without being a people’s person,’ he says. ‘It takes time, patience, and trust to shoot in this genre.’

A perfectionist of sorts, Mobeen revisits a place at least three to four times to ensure that the frame he has documented is just the one he wants. ‘I’ve been travelling to Hunza – a spectacularly picturesque mountainous valley in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan – for 20 years,’ he says. ‘I still go there 4-5 times a year but more than the landscapes (which is what it is famous for), I focus on human-interest stories primarily,’ says the photographer, who was a part of Bill and Melinda Gates’ foundation assigned to capture the heroic efforts of health workers who administer the polio vaccine in Pakistan. These health workers reportedly face death threats and work in situations that are often tense and volatile.

Environment as a prop

What does he look for when photographing people? ‘I take portraits in two styles – or lenses, if you may: Wide and portrait,’ says Mobeen. ‘With wide, I try to capture [the subject] as being one with their environment. I use their world as a prop to tell their story.

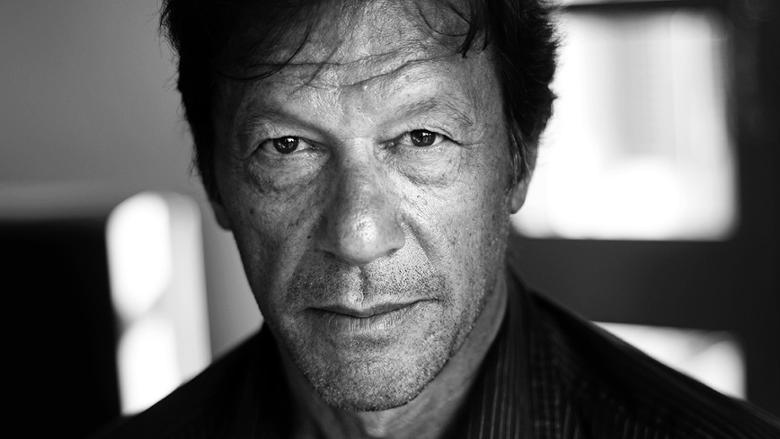

‘With close-ups, I capture them on a more intimate level. Most of my close-ups end up being black and white.’

Why?

‘Canadian photographer Ted Grant summed it up well when he explained his choice of shooting portraits in black and white,’ says Mobeen. ‘He said: “When you photograph people in colour, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls.’’

‘In both styles, I aim to capture their stories with utmost honesty, and in different ways,’ says Mobeen, who has also made two internationally acclaimed documentaries. While the first, Hellhole (2016) was based on the life of gutter cleaners and is told through the eyes of one such worker, the second, Lady of the Emerald Scarf, (2018) was set in a village in Gilgit-Baltistan. A silent film, it tells the tale of Aziza, a carpet maker and shepherd, and the bond she shares with her surroundings.

A motivational speaker who has given two TED Talks, Mobeen insists that it is important to always seek the consent of subjects before photographing them. ‘You have to respect cultural sensitivities,’ says the photographer who upholds originality, aesthetics, healthy competition and ethics when practising his craft.

One of the most interesting communities he has photographed is the Kalash. While some experts believe that they are descendants of Alexander the Great’s soldiers, others trace their history back further. ‘Their celebrations and festivities have always been fascinating to cover. Their most sacred festival is Chowmos, which coincides with the winter solstice and lasts over 20 days. It starts after sundown when they dance, light big fires, go door to door and sing for the prosperity of every person in the village. The celebration continues through the night.’

Portraying Imran Khan

People of remote communities and religious festivals are not the only subjects he has captured on film. From Imran Khan – ‘I requested for 15 minutes but 9 minutes were spent in conversation’ – to Pakistan women’s cricket team captain Sana Mir – ‘an icon and much respected by people’ – to a cemetery in Karachi where tombstones are engraved not just in English but also in Hebrew and Marathi, Mobeen’s repertoire is vast and varied.

What lessons about people has he picked up over the course of his interactions?

‘The most important thing I’ve learnt is that conversation is key to everything. Engaging with people and letting them speak will allow you to get to know them better, and for them to trust you. Trust is crucial in how they’ll portray themselves to the lens.’

Another factor is time. ‘Most celebrities get very uncomfortable with long-duration shoots,’ he says, adding the power of positivity and humour are crucial ‘to get you the pictures you truly want.’

Social media, he believes, has made it easier for a photographer to connect with the world and promote one’s work. ‘However, I also believe that we are at a point where the line between ‘social media influencer’ and ‘artist’ is blurred in many instances, and that affects creativity.’

What does he want his pictures to tell people?

‘I talk about a variety of topics in my photography – from highlighting unsung heroes, to climate change, to preserving heritage, and celebrating diversity. In all this, I talk about humanity, and that we are all a global village. Each of us has a story. I like photography to be the [medium] of that.’

Mobeen in the UAE

Mobeen Ansari will be showcasing his works in Dubai, Sharjah and Abu Dhabi. The events are open to the public and are free to attend. In Dubai, the exhibition and book signing is from September 17-28, at Studio Seven Gallery, Oxford Tower, 804, Business Bay. In Sharjah, he will conduct an exhibition, screen his short films and participate in a seminar from September 19-22 at the Expo Centre. In Abu Dhabi, the exhibition and book signings are on September 30 and October 1, at Etihad Modern Art Gallery.

Tips for wannabe photographers

• Practise, practise, practise. Experiment with new forms of lighting, find challenging subjects/circumstances to shoot, keep up with technology.

• Find inspiration everywhere. Look at works of photographers around the world. It helps to break patterns and try something new.

• Push your limits; go out of your comfort zone. I’ve done it too. I visited Hunza (North Pakistan) in the peak of winter when temperatures drop below -30C at night, but the scenes I witnessed were incredible. In the midst of snowfall and blue skies, I’d see a house with firelight emanating from the window; animals such as the ibex descending for grazing…. I’ve also captured human interest stories of struggles with this harsh climate.

• Keep fewer lenses. There was a time I’d use 6 lenses; now I use 2.

• Interact with people and places that you shoot. Even if this means keeping in touch long after you have left the place.

To quote Ara Güler again: ‘It is pure injustice to spend less time at one place.’ He once wrote: ‘I had taken hundreds of photographs and conducted many interviews. When I took them to Bob Gilka, photo editor of National Geographic, his first question was “How long did you stay in Mongolia?” When I said 10 days, he responded, “I will not consider your reportage, no need to look at the photographs”. “What! I took over 1,500 frames, wrote a lot of pieces, is there no chance?” and his reply was “to know a country you have to feel it, stay at least three months. We can only print such reportages in our review”.

I’ve been travelling to Hunza for 20 years, and with each time, [I learn more] of the regional languages and keep a strong bond with my local friends, which has helped me tell stories that would have otherwise been impossible to tell.