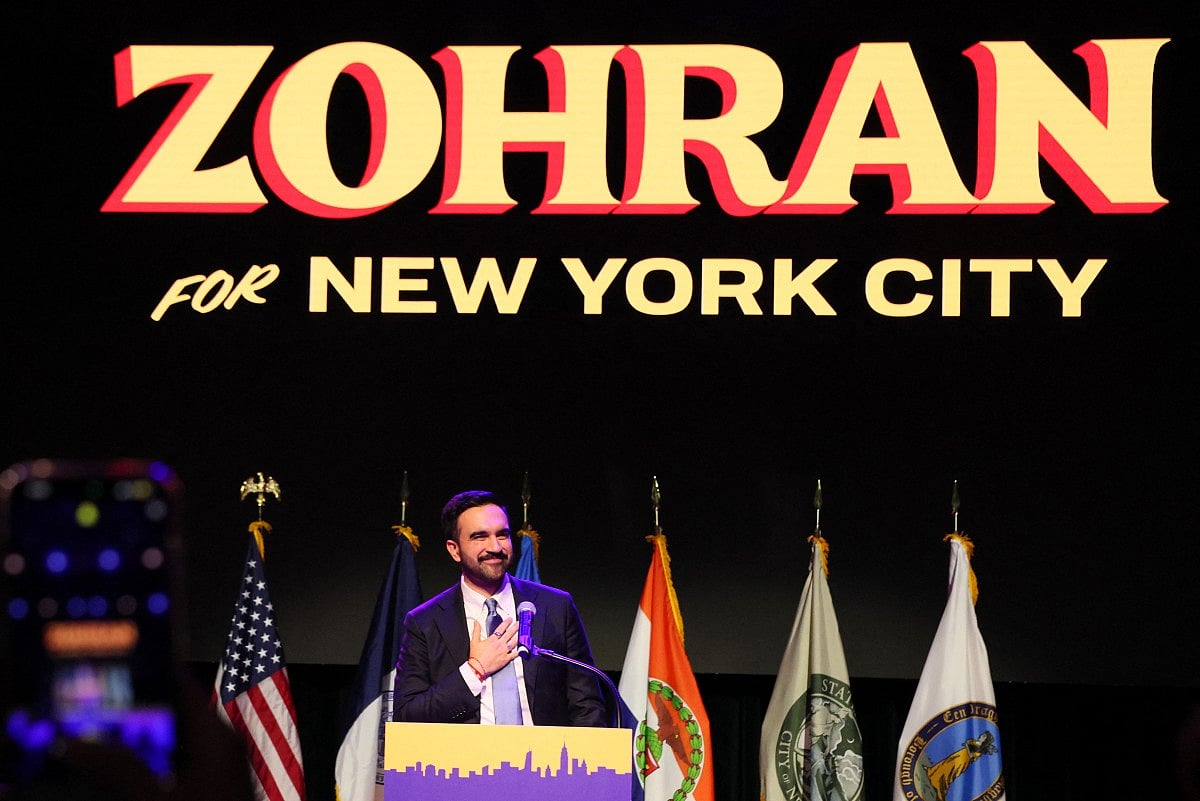

Zohran Mamdani has won: What does the New York City mayor actually do?

As Mamdani prepares to take office, here’s what powers define City Hall’s demanding job

When Zohran Mamdani takes the oath of office as New York mayor on January 1, 2026, he will inherit not just a historic mandate but one of the most powerful municipal roles in the world — a post that operates as both head of government and chief public manager for a city of 8.5 million people.

Under the New York City Charter, the mayor is responsible for the “health, safety, and welfare” of residents. That means turning political promises into operational realities: keeping the subways running, the streets safe, the schools open, and the city solvent.

The city’s chief executive

The mayor functions much like a governor within city limits. He or she appoints commissioners to run about 45 departments and agencies — including the Police Department, Fire Department, Department of Education, Sanitation, Housing Preservation & Development, and the MTA-linked transit offices. The mayor also appoints deputy mayors to oversee clusters such as housing, operations, and public safety.

All city spending flows through the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, which drafts an annual plan exceeding $110 billion. That proposal must then be approved — and often amended — by the 51-member City Council. The council can hold hearings and override vetoes with a two-thirds vote, keeping the mayor’s influence powerful but not absolute.

Quick takeaways:

The NYC mayor is the city’s chief executive under the City Charter

Oversees more than 325,000 employees and a $110 billion-plus budget

Controls 45 city agencies but must work with the City Council

Coordinates public safety, housing, transport, and emergency management

Balances local policy with state and federal oversight

Guardian in crises

Beyond bureaucracy, the mayor leads the city in emergencies. From hurricanes and blizzards to terrorist threats, the Office of Emergency Management reports directly to City Hall. During the COVID-19 pandemic, previous mayors exercised sweeping emergency powers — decisions that shaped everything from school closures to vaccination drives.

Public face and political negotiator

New York’s mayor is often the second-most recognised political figure in the United States after the president. The officeholder represents the city’s interests to Albany and Washington, lobbying for transit funds, affordable-housing grants, and federal disaster aid. Maintaining those relationships can determine whether campaign promises become policies.

At the same time, the mayor must balance dozens of competing constituencies: powerful unions, real-estate developers, immigrant communities, and watchdog activists. Success depends as much on coalition-building as on executive command.

Limits of power

Despite the title’s grandeur, the mayor cannot unilaterally raise or lower taxes — those decisions lie with the state legislature. Control over public education, too, is periodically reviewed and renewed by Albany. The mayor can propose reforms but must work within a dense web of state laws and federal regulations.

What awaits Mamdani?

For Mamdani, that structure means his ambitious pledges — rent freezes, free buses, and city-run groceries — will require cooperation with both the City Council and Governor Kathy Hochul. How he navigates those relationships will define whether his administration’s “mandate for change” becomes tangible progress or stalls in political gridlock.

In short, the mayor of New York is less a monarch than a master negotiator — a leader whose real power lies in persuasion, persistence, and the ability to turn a restless city’s energy into workable governance.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.