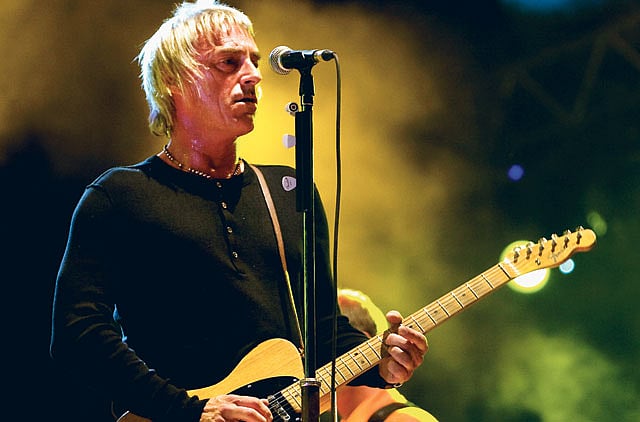

Paul Weller: The evergreen man of pop music

Paul Weller refuses to let age come in the way of his rediscoveries

Paul Weller is having his photo taken. Which he doesn't mind, as he is self-confessedly vain, but which he does mind, because he is vain. "I look all right from a distance," he grins, "and I feel the same in myself as I did when I was 30. But close up I've not had Botox, no. I thought about fillers but I got talked out of it. Sunbeds? Well, this tan is from my holiday but I've been thinking I might top it up."

Of course, he looks great: A steel-grey silver fox these days but still flash in light parka and kick flares, quite the dandiest man in Blacks, the Soho club where we meet.

What was the last item of clothing he bought? "Some shoes and a jumper from YMC on the way to this interview. So, do you want a cup of tea?"

It is a polite request, delivered with Weller's usual abrupt impatience. Yes, please, Paul. Don't get cross.

Everyone knows Weller. He is a pop music constant, with his undying stylishness, his unfading anger, his never-ending devotion to what he deems "proper" music, whether soul, rock, house, folk or R'n'B. And yet, his career has seen him flicker in and out of favour, mostly through his own wilful refusal to dig the same musical furrow. Going Underground, My Ever Changing Moods, Wild Wood, You Do Something to Me: all great, all completely different. How strange that he was once blamed for the stultification of indie music, for being boring and predictable and directly responsible for Britpop's tedious successor, Dadrock.

Just in the past two years, as he turned 50, he has brought out two thoroughly surprising LPs: the lengthy, romantic and critically lauded 22 Dreams, which he describes as "us trying to be as indulgent as we could, really"; and now Wake Up the Nation, compact, dense and whirling with off-beat sounds.

There were a few album playbacks late last year, he confesses, where he could see that by the end, people were a bit like: "Oh, I've got to get some air."

"It's challenging," he admits, "but there is nothing wrong with challenging your audience. It shows respect, rather than putting out the same thing every year."

Wake Up the Nation is different because it was made differently. Instead of Weller turning up to record his own compositions, co-producer Simon Dines, who worked on 22 Dreams, sent him some musical ideas: "sound collages, little mood pieces". Weller, who wasn't planning on making another LP, found himself inspired. So he and his band went into the studio and built up Dines's tracks through playing. "Then they would go: ‘All right, time for a vocal.' I'd be bricking it because I hadn't even got a melody or words but I'd think: ‘Right, just open your mouth and see what happens.' I hadn't really done that before."

The result is intriguing: Weller's voice is often less dominant, lower in the mix, with him playing around with the tone. On Aim High, he tries out a falsetto; on Andromeda, about a man leaving a dying planet, he sounds like David Bowie (unintentional, he says, though he is a recent Dame David convert). And, from a man who has often mangled his lyrics, worked hard to get them to rhyme, or to reason (think of no bonds can ever tempt me from she from the Jam's English Rose, or I really like it when you speak like a child from the Style Council's Speak Like a Child), it is surprising to hear the admission that "sometimes it's nice, as a singer, just to sing words that have a flow and a rhythmic feel to them; they haven't always got to make sense". Which goes some way in explaining the puzzling: Two fat ladies at my door/Over the hills and far much more/Seeking the teats of mother and child/Some marked bitter others mild (Two Fat Ladies).

Though only four tracks of Wake Up the Nation's 16 are over three minutes, there is a world of different types of music in there, many varied moods: No Tears to Cry is like Dusty Springfield; Fast Car/Slow Traffic is very Jam; Moonshine is Weller's favoured driving R'n'B; and Pieces of a Dream has cascading piano, Doors-style organ, rock riff guitar. There are flashes of Blur, Marvin Gaye, the Beatles, even prog; on Trees, there are five separate pieces of music underpinning a lyric experimental prose, really that has Weller assuming different characters, including a young woman and a mother.

Trees was inspired by the visits Weller made to his dad, John, when he was in a respite home. John, a determined, loyal man who managed Weller for his entire career from the mid-70s, died in April 2009 after four years of illness.

Weller's mum, Ann, cared for him while he was ill but he stayed for two weeks in a home to give her a break, around Christmas 2008. There were many older people than him there — two old ladies on Zimmer frames were constantly wobbling into his room, thinking it was theirs — and Weller remembers the residents as "little fossilised trees, all gnarled and curled up. But there were pictures on their doors of when they were young. They were mothers, beautiful young women, strong, proud, young men reduced to this strange level, this in-between world where they're just waiting to go, waiting to die. Trees was me imagining what their lives were like before."

He says that he dealt with his father's death "all right": He found it a relief. "Seeing him when he was dead, laid out in hospital, wasn't as bad as when I saw him a few weeks before, when he was a man in anguish and torment. Awful. He hadn't been himself mentally and that was harder to deal with."

You might have expected Wake Up the Nation to be an elegy to John but Weller didn't want to do that. Instead, he wrote a poem that was read at the funeral. "My dad's spirit is still with me. I haven't really worked out what happens when we die. I think we go into the ether, into the earth, into the air, people's minds. But the whole notion of heaven and hell is man-made: You can live in either here on Earth and sometimes it's your fault and sometimes it's put upon you."

Naturally, with his dad's death, Weller has become more conscious of his own mortality ("I am aware of the words ‘national treasure' being attached to me occasionally. It just makes me feel old"). Now 52, he finds himself wanting to make more and more music, to leave a body of work behind when he does go.

"So many bands aren't around any more and the only thing you can look back on is one or two records. You don't get any real perspective on them, there's not enough to go on."

He feels happier now he is older, "not out to impress anyone in particular, just doing my thing and comfortable with that".

Not that he is always what you might call age-appropriate. Recently, there was an excruciatingly hilarious YouTube video of him with his new girlfriend, Hannah Andrews, in Prague. Weller gatecrashes a pub singer's gig to sing his own songs such as, well, a pub singer, and, later, Hannah and Paul end up on the pavement.

The Prague palaver came after the stick he got for getting together with Hannah at all: He left Samantha Stock, his partner of 13 years, for her 16 months ago and, at 25, she is less than half his age. Now they live together, in Maida Vale, north London, and Paul is very happy, despite the headlines. "Because she's so much younger than me, the press was all, it's a midlife crisis. ‘Wrinkly Rocker', ‘Mutton dressed up as ram'. But it isn't like that. We're really in love and that's that."

Weller has five children from three women: budding musicians Natt and Leah, 22 and 18, from his relationship with D.C. Lee; 14-year-old Dylan, who lives with her mum in Los Angeles; and Jesamine, 10, and Stevie Mac (nearly 5) from Sam.

"I think, generally speaking, in the past 15 or 20 years, the English have become quite forward-thinking. We're open, quite welcoming and much less xenophobic and racist. I think it's the politicians who are out of step with us and I still see the royal family as top of that horrible rotting pile that is the establishment. It's a shame we haven't got anyone who can stand for us. It's really sad when you see a million people on the streets demonstrating against war — well-meaning families, proper people, not mad anarchists — but it's like, look it's a nice idea but we've made our plans.

"People say that if you're still angry at 52, you're not an angry young man, just a grumpy old man. But why should I get to a certain age and go: Yeah, that's OK. Why do I have to accept everything? If you don't want it, say so, and if you want to kick against it, you should do that as well, whatever age you are."

Like the man says: Wake up the nation. We move on to less frustrating topics: how chuffed he is that his two eldest children are musicians.

"Natt joined us on stage in Leicester and it was one of the proudest moments of my life. Being a musician is a noble profession. Much more noble than an accountant or a lawyer, though I like my accountant and my lawyer." He does: He still has the same team around him that he has had for years, so that, post-John, he can function without a manager. When his record deal comes up (which will be soon), it will be Weller and his lawyer who meet the record company execs. And if there is no deal, he will be happy to go independent again, as he did after Polydor refused to release the final Style Council record in the late 1980s.

Which gives us an excuse to talk Style Council.

"Everyone really hated us," Weller says. "But what was worse was history being rewritten to say that no one ever liked the Style Council. From 1983 to 1985, we were big, every record was on the Top 5, No 1 albums, massive gigs. The balance has been restored a bit recently. For 22 Dreams, some reviews said: ‘Weller at his most experimental since [the Style Council's] Confessions of a Pop Group.'"

Of course, the Style Council was about Weller shucking off the Jam, stopping because he felt hemmed in. He did everything he could to annoy the Jam fans; playing pretty soul, getting lyrics translated into French.

"It was fun at the time," he says. "I was trying to smash whatever preconceptions people had of me, destroying them."

Is that what you are doing now, with 22 Dreams and Wake Up the Nation?

"No. Then I was just too horrible, nasty about it, like, don't box me in! Lashing out. Now I'm trying to challenge people but say, come with me, it's going to be good. It's great to be able to change, go on a journey, develop and take an audience with you. Because if it works out, we're all going to be happy."

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.