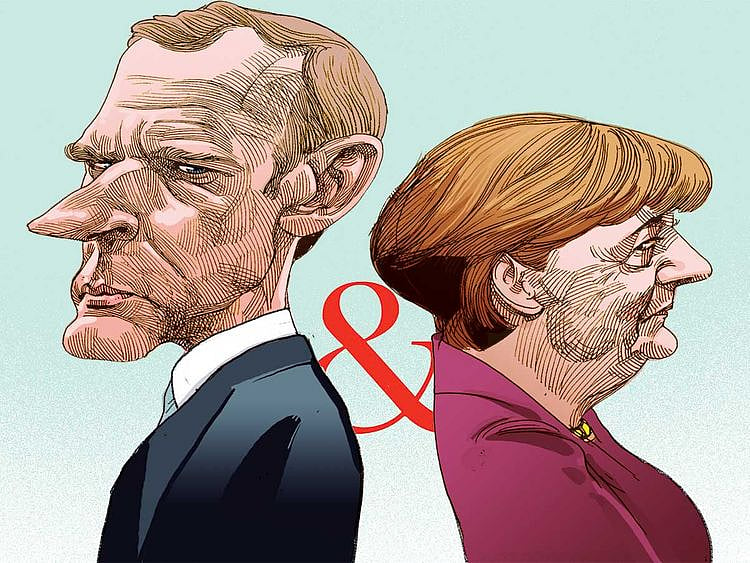

Two days after he took office as France’s President, Emmanuel Macron flew to Berlin. It was May 16, 2017, and France and Germany needed a reset. Joined at the hip, the two nations cannot make Europe work if they don’t work together. Macron had been elected to transform France, and he was convinced that real change in his country would happen only through better European integration.

Hope was in the air as the young, ambitious but untested French president met Angela Merkel, the stern three-term German chancellor. Two years on, the results are nowhere to be seen and the charm has given way to exasperation. When Merkel and Macron met on the sidelines of a Berlin summit on the western Balkans, last month, their talk was kept to a strict minimum — 15 minutes. Asked at a news conference about the French-German relationship four days earlier, Macron answered in unusually blunt terms. He openly admitted for the first time that France disagreed with Germany on Brexit strategy, energy policy, climate change, trade negotiations with the United States — and the list could have been longer. Macron went on to suggest that “the German growth model has perhaps run its course.” In his view, Germany, having made belt-tightening reforms that were right for its own economy, had fully benefited from the imbalances created within the Eurozone; especially hard hit were the Southern economies like Spain, Greece and Italy, for which austerity was bitter and destabilising. These imbalances have worsened, Macron pointed out, and they now “run counter to the social project” he supports.

Macron no longer wants to be treated as the chancellor’s junior partner, who would keep quiet if not asked for his opinion.

There is some irony that this newfound assertiveness from the French president towards Germany comes at a time when six months of social unrest from the so-called Yellow Vests — who have taken to the streets, sometimes violently, over France’s growing gap between rich and poor — have seriously weakened Macron’s leadership. But it is precisely because his house is on fire that he is losing patience with his biggest, wealthiest neighbour.

The new tone towards Germany comes neither only from Macron nor from Paris. Grievances differ, but they all point to one problem: Political paralysis in Berlin. Several governments in the Eurozone want Germany, the biggest economy in the bloc, to relax its fiscal rules and invest in infrastructure and innovation in order to provide stimulus. When Europe is assailed from all quarters in a world in turmoil, when most governments in the union are fighting a populist wave, Germany’s ruling coalition is behaving as if it were still navigating the calm seas of the early 2000s. “Germany has not moved for the past 10 years,” a German senior executive working for a foreign company told me angrily.

Many French experts blame Macron for placing all his bets on close cooperation with Merkel at the outset instead of reaching out to a wider range of allies within the European Union. Back in 2017, in order to win her over to his far-reaching plan for Europe, he intended to institute the domestic reforms, starting with new labour laws, that his predecessor, Francois Hollande, had been too weak to pass.

But German scepticism over France’s ability to deliver “was impossible to overcome”, Shahin Vallee, an economist and a former adviser to Macron, wrote in the Guardian. French officials think the Eurozone is at risk of collapsing, while the Germans are happy with the status quo. In Paris, disappointment over Germany’s failure to follow through on European reforms under Merkel is turning into resentment.

Yet, the party may be over even for Germany. Challenged by competition from China and slowed by global trade tensions, the export-powered German economy is sputtering. The German model needs to reinvent itself. Within Germany, a few audacious experts are starting to question its economic orthodoxy and to challenge one of its most sacred cows: The “schwarze Null”, or “black zero”, a 10-year-old fiscal rule that bars the government from running budget deficits. Of course, there may be a measure of jealousy among Europeans, including the French, who were not brave enough to reform their economies when the weather was fairer. But beyond concern that German conservatism hurts the Eurozone, there is a genuine sense of alarm, shared by many foreign policy experts in Berlin, about how Germany sees its role in a changing world — and how it sees the role of Europe, in which it is now so deeply anchored. When it comes to protecting its car industry, its gas pipeline with Russia or its political decisions on which countries to sell arms exports, Germany’s unilateral behaviour is increasingly at odds with Merkel’s much-acclaimed commitment to multilateralism.

In his list of items of discord, Macron mentioned neither Germany’s retreat on military spending, despite multiplying threats from Russia, China and terrorists and heavy pressure from President Donald Trump, nor did he discuss its reluctance to take a stand on major strategic and security issues, perhaps because these subjects are so sensitive. Or perhaps because Macron has not lost hope in his efforts to make Germany more European, rather than making Europe more German.

— New York Times News Service

Sylvie Kauffmann is a renowned French journalist. She was the first female to serve as the executive editor of Le Monde.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.