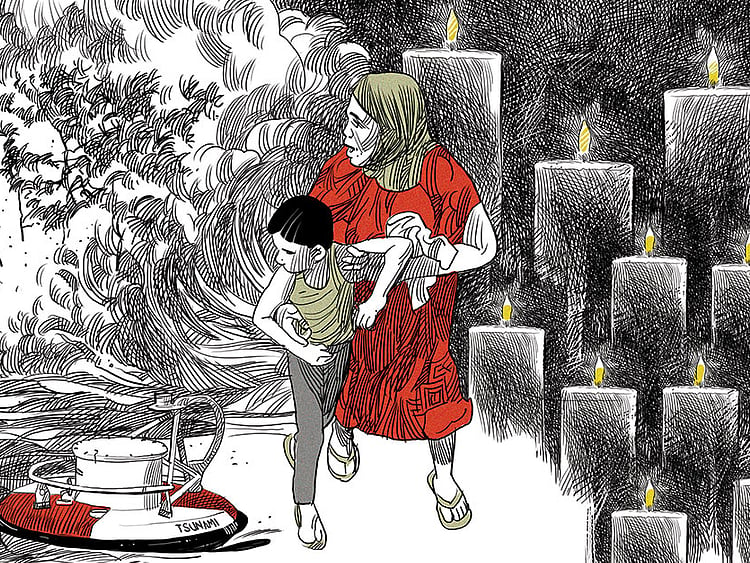

When the sea suddenly receded on Boxing Day 2004, after one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, Sofyan Umar ran down the beach to catch marooned fish like thousands of others across the conflict-ridden Indonesian province of Aceh.

Minutes later he and his family were swept up by the biggest wave they had ever seen, the wave that changed everything. “It was terrifying,” says Umar who lives in the coastal city of Meulaboh, which was ground zero for the tsunami. “For eight hours, I had no idea if I was on land or sea.” Clinging to flotsam and dodging cars, fishing boats and other debris, he managed to survive the 2004 Asian tsunami. But he could not save his wife, who was washed out to sea and never found.

The tsunami surged up to 6km inland in Indonesia’s northernmost province, wiping out 120,000 houses and killing 170,000 people. Outside Indonesia, 60,000 died in India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and beyond. The 9.2 magnitude undersea quake, which unleashed 1,500 times as much energy as the Hiroshima atomic bomb, and the waves of up to 40 metres that followed made it one of the world’s most destructive natural disasters.

But for Umar and 4 million other Acehnese, there was a silver lining. In the most religiously fervent province of the world’s biggest Muslim-majority nation, many even describe the tsunami as a “gift from God”. The unimaginable scale of the devastation pushed the Indonesian government and separatist Free Aceh Movement (GAM) to end a 30-year conflict that had cost thousands of lives, hamstrung the province’s once-thriving economy and left many in poverty. They signed a peace deal in August 2005.

“The violence only stopped because of the tsunami and that has allowed our economy to start growing again,” says Umar, 56, who remarried a woman who lost her husband in the disaster — one of many such “tsunami weddings”. He works as a foreman at Meulaboh port, which was built with Singaporean aid, supervising the loading of coal from a recently established mine. The 1,000 people who work at the mine would not have jobs if the tsunami had not ended the fighting.

Threatening prospects

After the peace came $7.2 billion (Dh26.48 billion) of relief funds from international donors and the Indonesian government in one of the world’s biggest and most complex disaster reconstruction efforts.

It left Aceh with some of the country’s best roads and hospitals, 140,000 new homes and 1,400 new schools.

The funds also gave a big boost to the economy, turning Banda Aceh, the regional capital, into a boomtown with new hotels, two shopping malls and coffee shops full of students working on laptops and smartphones. However, the province’s young population is more concerned about the future than the past. Corruption, economic stagnation, environmental degradation and the politicisation of Islam are threatening Aceh’s prospects.

Like the rest of Indonesia, southeast Asia’s biggest economy, Aceh is finding out the limits of an economy built on consumption and natural resource extraction. But its problems are more acute.

While Indonesia’s economy grew at 5 per cent in the third quarter, Aceh grew at just 2.7 per cent, the second slowest rate of the country’s 34 provinces. About 18 per cent of Acehnese live below the official poverty line of $0.95 per person a day, well above the national average of 11 per cent. Rather than tackling the province’s problems, the former fighters who run the local government under a special autonomy deal with Jakarta squabble over contracts, politics and Islamic dress codes for women. In Aceh’s many mountainous hamlets and fishing villages, people are struggling to make ends meet, facing new threats from floods and droughts, and harassment from the police, who uphold Islamic law.

Not enough

“After the tsunami, people made a lot of money from the international NGOs, but that ran out after five years,” says Teuku Ahmad Dadek, the head of planning for the local government of West Aceh, which incorporates Meulaboh. He argues that physical reconstruction was successful but that infrastructure alone does not generate economic growth. “Now we have beautiful roads thanks to American and Japanese money but we don’t have any new jobs.”

Many large post-disaster aid operations are failures, with donors not delivering or money pilfered by greedy officials. Relief workers cite the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and the 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran, as examples where promises of billions of dollars in aid either did not materialise or were frittered away.

Former minister Kuntoro Mangkusubroto was put in charge of ensuring Aceh was different. He headed a special body to co-ordinate the reconstruction effort, with the aim to “build back better”. Mangkusubroto says it was a “nightmare” trying to co-ordinate more than 700 NGOs and multilateral agencies, thousands of foreign workers, plus the military and the separatists, who had just put down their guns. Mistakes were made, with NGOs supplying river boats to sea-fishing communities, homes being rebuilt in prohibited coastal zones and shoddy new buildings falling down.

In the end, the money was spent and the eventual result was a recovery effort “the likes of which we haven’t seen before or since”.

But Mangkusubroto is another who worries about the future. “There have been no major investments in Aceh since then,” he says. “We have all this infrastructure but it is mostly moving people, not cargo.” Sidney Jones, a conflict analyst who studies Aceh, says the peace dividend was followed by “10 years of really lousy governance”, and that reconstruction enabled some GAM leaders to become extremely rich, while generating a “big gap between the haves and have-nots”.

Residents such as Saiful, a 65-year-old from the rebuilt coastal village of Kuala Bubon in West Aceh, share this concern. “Of the 118 households here, there are only four who have been able to send their children to university,” says the fisherman who, like many Indonesians, only goes by one name. “Before the tsunami, we used to be one of the most successful fishing villages around. But the old generation was wiped out and the new guys don’t have the skills, training or equipment. They make enough money to survive but not enough to educate their children properly.”

A US NGO built an ice factory in the village and provided new nets and boats but they have fallen into disrepair, says Saiful, who escaped the tsunami by fleeing to higher ground with 44 others in his small pick-up truck. While he stayed near the sea, 42-year-old housewife Safridah was one of many who opted for relocation inland, after two years in a military barracks. Having lost a son and injured her face badly during the tsunami, she could not live with the trauma of hearing the sea every day. But the new village outside Meulaboh, in which she lives with 2,000 other survivors, has another problem — flooding in the rainy season.

‘Growing disaster risks’

Rina Meutia, a former disaster management expert for the World Bank, says this example of bad planning is symptomatic of the limits of humanitarian aid. “It’s only a Band-Aid that doesn’t address the real issues in Aceh,” says the 33-year-old, who stood as an opposition candidate in April’s provincial elections. Billions of dollars of aid cannot fix a government that is unable to deliver clean water, electricity and basic public services, she says.

“Now Aceh is facing growing disaster risks from floods and droughts because the government has been letting so many companies destroy our forests,” she says over iced coffee at Solong, one of Banda Aceh’s most famous coffee shops.

While the Aceh government of former rebels struggles to develop the province, it is stepping up its efforts to enforce a strict form of Sharia. Many Indonesian districts have some Islamic bylaws, but Aceh was given the power by Jakarta to enforce a wide-ranging code in 2001, and it is the only province with a dedicated police force. They stop and lecture women who wear tightfitting clothes or do not cover their heads, shut down cafes and shops during Friday prayers and publicly cane people engaged in gambling, adultery and proximity to unmarried members of the opposite sex.

“There are many interpretations of Sharia and to me, it’s not right to whip people in the street,” says Mohammad Noor Djuli, a former top negotiator for the GAM separatists. “Why are we concerned about what women are wearing when we have so much corruption and we lack basic hygiene?”

He says that Acehnese used to follow a more spiritual and less rule-bound version of the religion. “We never had these dress codes in the past,” he says. “In fact, our women used to wear trousers when they were fighting against the Dutch colonialists in the 19th century.”

‘Educate and inform’

Sensing that it has an image problem, the government appointed Syahrizal Abbas, an academic, to head its agency 18 months ago. “We are not like [Daesh] or the Taliban,” he says. He admits that the police often overstep the mark and want to train them better so that they “educate and inform” rather than intimidate women who are not dressed appropriately. And, with a gentle swish of the hand, he claims that the canings in Aceh are meant to act as a public warning rather than a form of physical torture. “Enforcing is the only thing that can make people’s lives better,” Abbas says. “Some people fear it because they do not have the correct information. A French diplomat recently asked if makes Aceh unsafe for international investors. But is good for business because it will ensure that all contracts are open and transparent.”

Meutia, who is setting up an NGO to focus on political education for young people, says women in Aceh feel growing pressure. She adds that even if the government truly believes it can help create jobs and reduce corruption, Aceh cannot be fixed from the top down. “We need people to realise they have the power to change the government and demand better services.” Like many young, well-educated Indonesians, Meutia remains torn between anger at how the corrupt elite has wasted the country’s potential and hope for change. “I’m very cynical about our current situation, but I still have boundless optimism that we can improve the future for our people,” she says.

— Financial times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.